Kenneth L. Feder Native America: The Story of the First Peoples Princeton University Press 440 pages, 6.25 x 9.25 inches ISBN 978-0691220451

In a Nutshell

Reading a non-fiction book can be like taking a journey through time and across space. The author is your tour guide. In Native America: The Story of the First Peoples, I guide the reader on an excursion through deep time and across the vast expanse of an entire continent, visiting the history of the Indigenous People who lived and continue to live here. Aided by metaphorical maps provided by archaeology, documentary history, and oral histories passed down by those Indigenous people, I help the reader navigate that story.

A major theme underpinning this journey is that we are not visiting an extinct people. My book isn’t a history of antique or marginal folks, or people who represent a side branch of the human story. Instead, we will encounter the remarkable legacy of a people who entered a literal “new world” more than 20,000 years ago, and who ingeniously and successfully crafted adaptations to the reigning Pleistocene or “Ice Age” environment characterized by enormous beasts like mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, and extinct forms of bison that make their modern cousins seem puny (Chapter 5 and 6).

These same folks continuously and creatively adjusted their strategies for survival as the Pleistocene waned and modern climatic conditions became established over the course of a few thousand years. Literally hundreds of unique post-Pleistocene native cultures developed, each with its own distinct lifeway, in a continent characterized by enormous environmental diversity. That diversity included deserts and semi-deserts in the Southwest, Arctic tundra in the far north, rich and deep woodlands in the East, near tropical conditions in the Southeast, vast prairies teeming with bison in the north-central plains, and enormously rich maritime habitats along its western and eastern shores (Chapter 8).

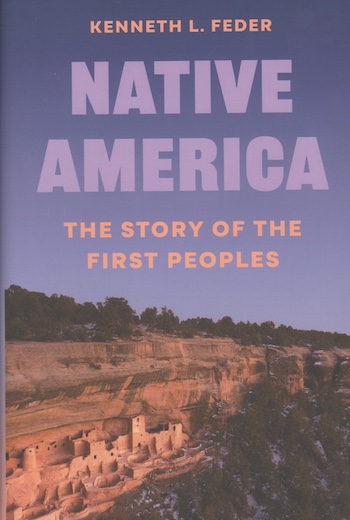

The stories we encounter as we travel through time in Native America have not been memorialized through written words pressed into clay, hieroglyphs painted onto sheets of papyrus, or stories inked by monks onto parchment. Instead, much of the story of Native America was written in the language of archaeology in the form of exquisitely crafted stone tools (Chapter 3); massive apartment houses and breathtakingly beautiful adobe castles in cliffs; (Chapter 14); monumental burial mounds, flat-topped pyramids, and earth sculpted into the form of massive bears, raptors, and even a snake (Chapter 12 and 13); marvelous works of art etched and painted onto sandstone cliffs and volcanic boulders (Chapter 16); and in histories passed down from grandparents to grandchildren, and from those grandchildren to grandchildren of their own (Chapter 2). These are the sources of Native history upon which I rely in our journey through time. Switching metaphors here, the crucial truth to take away from my book is that the history of Native America is not a prologue, post-script, or a marginal note in the epic saga of humanity. Instead, it contributes its own remarkable and distinct chapter. I attempt to present that chapter of the human story in Native America: The Story of the First Peoples.

Cliff Palace is a truly remarkable testament to the architectural artistry of the Native People living in Mesa Verde, Colorado. This “palace” actually was an apartment house built and occupied between AD 1190 and 1300. It stretches the length of an American football field.

The wide angle

Let's get something straight right at the outset; I am not an Indigenous person. My ancestors arrived in America in the late nineteenth century, fleeing poverty and oppression in Europe. So my deep dive into archaeology with a particular focus on the Native People of North America took a circuitous path. It is rooted in a combination of fascination and respect. If anything most symbolizes that intellectual journey, it was an event that occurred to me in the early 1990s.

My crew was conducting our first year of field work at the Lighthouse site. It wasn’t an actual lighthouse; it was called that by stagecoach drivers who viewed the village as a sort of beacon in the wilderness. Dating to between the mid-1700s and the mid-1800s, the Lighthouse was a community of people of Narragansett, Mohegan, European, and African descent living in the northwest hill town of Barkhamsted, Connecticut. We were digging there for the primary reason that I thought the place and its story were exceptionally interesting.

A local television station covered our research in their daily news program. On the following day, while we were having lunch along the road that marked the edge of the site, a red pickup truck roared into the parking lot, ground to a halt, and a big bear of a man emerged. He walked over to where I was sitting on the ground, put his hands on his hips, and seemed to glare down at me. It was a bit disconcerting, to say the least. I stood up and meekly asked, “Can I help you?” The man thrust out his arm and demanded, “Shake my hand.” Of course I did and he then pointed toward the site and cracking a big smile said, “You just shook hands with one of them. I’m a descendant of Jimmy Chaugham.”

I was stunned. And ecstatic. James Chaugham was a Narragansett man from Block Island in Long Island Sound who, with his white wife Molly Barber, established the Lighthouse community in the mid-eighteenth century. The visitor was Mr. Raymond Ellis and between the two of us, we determined that he was a seventh-generation descendant of James and Molly. I invited Mr. Ellis to view our archaeological excavations and he eagerly accompanied me up the hill to examine the foundations, fireplaces, charcoal kilns, and the stone quarry that were located in the main part of the village. He lived in the area and when I asked him about the last time he had visited the site, he became very quiet. He told me that he had never been there because local people had always made fun of the “drunken Indians who lived up on the hill.”

That saddened me but nothing prepared me for Mr. Ellis’s reaction when we visited the village cemetery. As I did my standard lecture about the site, I looked up to see tears streaming down Mr. Ellis’s face. I felt terrible and apologized profusely for having saddened him. He looked at me and responded, “No. Do not apologize. Thank you for bringing me home.”

That moment changed me, both as an archaeologist and as a person, and it underlies my perspective, approach, and motivation on every page of Native America. As an archaeologist and an author, my goal is to bring people to visit the home of the Indigenous People of North America.

No, these more than 2,000-year-old pictographs in Utah do not depict extraterrestrial visitors to Earth. These likely were images of spirit beings.

A close-up

If a potential reader were to pick up my book, I like to believe that were they to turn to a random page, they would immediately be intrigued and drawn in by any of the many diverse cultures and histories I describe. The response I aim for from readers is “Huh. I didn’t know that,” getting them enthused for accompanying me on our adventure through the history of Native America. Being a bit more realistic, I think that I would direct readers first to the Prologue as it sets the tone of the book, preparing the reader for our journey.

One thing I try to make clear in the Prologue is that the book is about real people, people who we should credit for marvelous achievements in adaptations, in architecture, in art, in agronomy, and in astronomy. At the same time, a clear-eyed presentation shows that some groups engaged in warfare, some kidnapped people, and some practiced human sacrifice. In other words, the people of Native America shouldn’t be objectified or romanticized by stereotyping them, positively, negatively, or benignly. They aren’t symbols. They were and are people with all that implies for their genius, creativity, and inventiveness.

That’s one reason why I highlight in the Prologue the “Crying Indian” ad broadcast on TV as part of an anti-littering campaign in the 1970s. Readers of a certain age will remember endless re-airings of the heart-wrenching ad featuring Iron Eyes Cody (who actually was, as it turns out, Italian) canoeing through a pristine wilderness and coming ashore upon a polluted landscape. There, adding insult to injury, a thoughtless driver throws trash at his feet. The one tear streaming down the Native man's face in the final close-up gave the ad its sardonic name.

Though it seems innocuous enough, and appeared to present Native People in a positive light, as the conscience fueling the environmental movement, the ad presented them as powerless. The crying Indian is a ghost from another era. Instead of showing modern Native People actively trying to fight environmental destruction through protest, by voting, or by cleaning up the mess the Native person in the ad cries. Compare this to the genuine story of, for example, the Tunxis in Connecticut who, as I discuss in Chapter 18, were active participants for decades in legal proceedings to recover land taken from them. They didn’t just grin and bear it. They didn’t cry. They fought it in the courts. The Native People of North America weren’t naive waifs confronting a great civilization; they created their own distinct, unique civilizations who fought their subjugation every inch of the way, sometimes through warfare as shown in Chapter 17 (the Pueblo Revolt and the Battle of the Little Bighorn are good examples). The Prologue sets the stage for the rest of the book, a respectful treatment of a history too often stereotyped, romanticized, objectified, or simply ignored.

Rock art, like this petroglyph in Nine Mile Canyon, Utah, is likely more than 1,000 years old and provides the modern viewer with a peak into the minds of the immensely creative artists of Native America.

Lastly

As I was working on the book, I visited the Institute for American Indian Studies, a wonderful museum and research facility in Washington, Connecticut. While there, I photographed their outdoor exhibit that includes replicas of indigenous structures including a wigwam and a “longhouse.” The latter is more typical of the region to the west of the Hudson River, among the people who call themselves the Haudenosaunee, which, not coincidentally, means "People of the Longhouse.” You probably know them as the Iroquois (Chapter 10). I posted some of those photos on Facebook and received some very nice comments about the beauty and practicality of these structures modeled on Native homes in the Northeast that date to more than 800 years ago.

I also received one disparaging comment that, perhaps in my naiveté, actually surprised me. The person derisively pointed out how it was readily apparent from my photos that Indians were primitive and backwards, living in “mud huts” while, during the same period, Europeans were building churches and castles.

I found that level of ignorance and bias astonishing, even by the incredibly low standards of social media. Even just technically it was wrong; wigwams and longhouses aren’t “mud huts,” they were ingeniously constructed of bent saplings with thick bark, reeds, or expertly woven mats cladding the structures to render them waterproof. More important though is the fact that these Native structures, both in terms of their beauty and practicality, were more than equal to the houses of ordinary European folk living during the same time period. Further, it might surprise the person who reacted to my photos that most Medieval people weren’t living in castles. In that regard, instead of comparing apples to oranges—Native domiciles to European castles and churches—lets compare the clearly beautiful and impressive Medieval castles to marvelous Native architectural achievements like the multi-story, 800 room, 800-year-old apartment house called Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (Chapter 14). Or, why not compare an impressive European church from the same period to the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde, Colorado (Chapter 14). For example, Cliff Palace is ensconced in an alcove in a cliff, has multiple three- and four-story towers, and extends the length of a football field. To say that these Native architectural achievements are unworthy in comparison to European architecture of a similar age is nothing more than nonsensical bias.

The level of ignorance and thoughtlessness expressed in the response to my simple Facebook post about wigwams and longhouses should not be ignored and, to be honest, inspired me throughout my Native America book project. The indigenous residents of North America deserve attention and respect and I hope that in joining me in our journey, readers will come away with a new or renewed appreciation for Native America’s First Peoples.