Michael Leja A Flood of Pictures: The Formation of a Picture Culture in the United States University of Pennsylvania Press 400 pages, 7 x 10 inches, ISBN 978-1512826807

In a Nutshell

Pictures of all kinds in all media are so omnipresent, so naturalized in our 21st-century lives that a world without them is hard to imagine. Yet the picture-saturated culture we know today has a relatively short history. It began about two hundred years ago, when the mass production and mass marketing of pictures became viable and desirable. A Flood of Pictures tells the story of this development as it unfolded in the United States between about 1830 and 1860. At that time pictures began to permeate most areas of ordinary daily experience, and this transformed social and cultural life.

The book is written as a series of narratives. It identifies seven projects that were instrumental to the remaking of picture production for mass distribution in the US. Each project is the focus of a chapter. The first discusses the cheap newspapers of the 1830s—the penny press—whose publishers increased sales by providing illustrations of noteworthy events, such as fires, shipwrecks, and sensational crimes. In 1840 the political campaign of Whig presidential candidate William Henry Harrison was the first to rely heavily on pictures of the candidate, shown in portraits and in various scenarios. He trounced his opponent in the election. A profusely illustrated bible published in installments between 1843 and 1846 by the Harper Brothers in New York sold almost 100,000 copies and inspired a host of followers. Hundreds of thumbnail pictures drawn very simply in a style developed for children’s publications were the key to its success. The fourth chapter spotlights a large group portrait of the US Senate, with each politician’s face copied from a photograph. It provoked international demand that exceeded the limits its engraved metal plate could supply. Jenny Lind, a Swedish singer making a concert tour through the United States in 1850, was the first entertainer to become a national celebrity thanks in part to a string of portraits in all media orchestrated by her tour promoter, P. T. Barnum. The Langenheim brothers, photographers working in Philadelphia, introduced a series of technical innovations and marketing schemes that led to the development of mass-marketable forms of photography in the 1850s. And finally, Gleason’s Pictorial was the first magazine to successfully adapt for US audiences the revolutionary model pioneered by the Illustrated London News a decade earlier. It paved the way for enduring, influential followers, including Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News.

I believe this is the first study to propose a canon of significant projects that defined the formative period of the nation’s mass market for images. The choice of these case studies was governed by published commentaries from the period. The popular press referenced them for their striking success in the marketplace and their influence on aspiring picture makers. The case studies also represent as fully as possible a cross-section of the media, subject matter, and functions that combined to constitute the pictorial flood.

The wide angle

As an art historian I have been especially interested in works of visual art that have played some significant part in public conversations about pressing issues. In an earlier book I examined the paintings of Jackson Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists as elements of a culture-wide initiative to reimagine the self at a time when established beliefs about human nature and the human condition were coming to seem inadequate. Another book addressed the skeptical manner of seeing that developed as a social survival skill among Gilded Age Americans. How did artists respond to an audience of suspicious viewers? In such interpretative frameworks, fine art and mass visual culture often turn out to have more in common than not, and the already unstable boundaries between them fade.

A Flood of Pictures shares the concerns of these earlier studies insofar as it examines the material, social, and cultural conditions that fostered the mass production of pictures and were transformed by it. One issue that can serve as an example is the formation of mass markets. Any intrepid artist/entrepreneur in the mid-19th century US seeking to circulate fifty thousand copies or more of an image would have had to envision a demographic market of that size. This was no small challenge, given the radically heterogeneous and fractured population of the country, with vast differences in political or religious affiliation, ethnicity, rural or urban habitation, region, occupation, cultural and educational background, and class. In most cases at this time, Indigenous Americans, anyone of African or Asian heritage, and immigrants from many European nations were excluded from the target audiences envisioned for mass-marketing. In fact, much mass-produced imagery during this period was overtly racist and xenophobic, and it served effectively to reinforce the prejudices and exclusions already in place. Even within the limited diversity of envisioned audiences significant differences had to be overcome, and questions of inclusion and exclusion were essential. The case studies reveal that the mass audiences forged for these projects were different. They generated not one mass audience but many. Each project targeted a particular array of population groups with telling inclusions and exclusions. Not in all cases were the calibrations to certain groups explicit, but implicit ones were always in play.

One approach to this challenge entailed designing and marketing images in ways that avoided alienating any segment of the population that might have an interest in their content. Failure in this line was inevitable, but the ambition was resilient, and limited success was possible, as the example of Harper’s Bible illustrates. Another option was to exploit differences in the national population by rallying one part against a demonized other. The Whig campaign images produced for Harrison’s presidential campaign in 1840 abandoned established, unifying symbols of the nation in favor of personal symbols that drove a wedge into the electorate. A third alternative was carefully manipulating component populations through clever promotional schemes. Deep class divisions could be left in place while multifaceted marketing strategies appealed to different groups. The painstaking management of Jenny Lind’s image epitomizes this approach.

A close-up

I imagine that a curious reader browsing through the book would first be intrigued by the pictures. Identifying, gathering, and preserving pictures important to the early history of mass visual culture in the US was a key aspect of this project. Although these pictures were produced in very large editions, their materials were ephemeral, and many are now rare. Some no longer exist in their original media but only in disappointing microfilm copies. Some seem to be lost entirely.

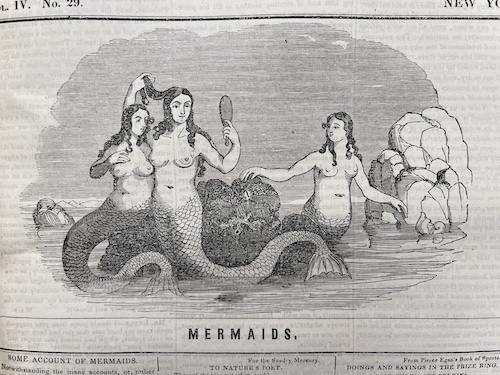

The book reproduces three wood engravings that P. T. Barnum arranged to have published on the front pages of three different New York newspapers on the same day in 1842 (see pages 78 and 79). All portray mermaids. This was an advertising stunt masquerading as news items. The pictures and accompanying essays were intended to raise the question of the existence of mermaids in conjunction with a new exhibit at Barnum’s museum. He was hosting the so-called Feejee Mermaid, a dried, blackened object made by stitching together nearly invisibly the torso of a monkey and the body of a fish. Barnum urged prospective patrons to view the exhibit themselves so they could decide whether it was real or fake.

A portrait of Andrew Jackson, made just two months before his death, was published in the Democratic Review in 1845 (page 168). It looks like a photograph, but it was made before mass printing of photographs was possible. Even more remarkably, it anticipated the look photographic prints would have in a decade or two, when new processes introduced paper prints with distinct forms and a broad tonal range. A talented engraver named Thomas Doney produced the printing plate from a daguerreotype by photographer Edward Anthony (reproduced on page 172).

Another noteworthy illustration shows the front page of the first issue of Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, published in 1851 (page 297). Market demand for this illustrated weekly magazine was so great that by the third issue the publishers realized they would need to make adjustments. They regrouped and started over with a new format, larger print run, and more pictures. The illustration on the original front page shows the bustling Quincy Market building at Faneuil Hall in Boston, the hometown of Gleason’s Pictorial. The picture was drawn by a staff writer for the paper. The fact that a writer was pressed into service as an illustrator calls attention to the challenges posed by the shortage of capable artists and wood engravers in the US at the time. I have been able to locate only one surviving copy of this initial issue.

Mermaids. Sunday Mercury (New York), July 17, 1842, p. 1. Wood engraving, artist(s) unidentified. Library of Congress, public domain.

Lastly

While I was writing this book, the immediate response I would most often get from people when they heard the title was “so it’s about the invention of photography?” There are two problems with this response. First, it attributes the flood of pictures to technological innovation. Rather we should wonder why a particular sort of image technology was sought by inventors at precisely that time. In the case of photography we know that between 1790 and 1840 at least 20 different people were trying to find a means of fixing the image projected by a camera obscura. Second, it assumes that photography was a mass medium from the moment of its invention. On the contrary, photography’s transformation into a viable mass medium was the result of sustained effort over many years. Several other picture technologies—wood engraving, lithography, steel engraving, electrotypes—were immediately capable of producing tens of thousands of copies of an image. These were the technologies that enabled—not caused—the flood to begin. The fact that so many high-volume image technologies appeared in a span of about 50 years is a clear sign of intense historical pressures.

This book tries to understand these historical pressures by looking closely at early mass-produced pictures—who was making them and why, what functions they were serving, and what benefits and costs they entailed. The case studies show that mass-produced pictures rapidly assumed many important functions. They supplemented verbal texts—and in some respects overshadowed them—for conveying news and information; portraying people, places, and events; focusing public discourse; selling things; educating and instructing; generating excitement and aesthetic gratification; promoting and disguising political agendas; shaping social identities; and building and undermining social bonds. Pictures were invaluable to wide-ranging communication needs of a new mass society and an expanding capitalist market. As a result of the flood, all sorts of individual and collective experiences were increasingly mediated by visual representations. Modes of perception and cognition were changed by it.

A direct line connects this formative moment with our present one. Beginning in the mid-19th century every generation has commented upon the exponential growth in the numbers of pictures circulating in their incessantly modernizing world. The book lists a series of these comments. For example, already in 1860 one magazine noted that “Photography threatens to flood the world with the amateur performances, on paper, of the Sun. Stereoscopic ‘views’ are becoming as thick as autumn leaves, and almost as cheap. Lithographs are everywhere -- even on posters and billheads, and the promise is that ‘the masses’ will not famish from want of something to look at. We may well characterize this era as that of promiscuous production in the way of pictures.” To call the production of pictures “promiscuous” was to say that picturing was being used more often than was necessary. Unmistakable anxiety was mixing with excitement.

I hope the book will focus our thinking about pictures, give it a historical framework, and provoke reflection on the extent and strangeness of our present cultural dependence on them.