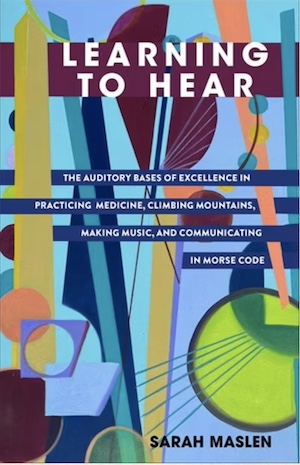

Sarah Maslen Learning to Hear: The Auditory Bases of Excellence in Practicing Medicine, Climbing Mountains, Making Music, and Communicating in Morse Code Columbia University Press 280 pages, 6 x 9 inches, ISBN 9780231217897

In a Nutshell

My book examines the tricks of the trade and forms of collective support for crafting our largely unconscious practices of hearing. As we live our daily lives, our hearing generally seems something that we “have,” not something that we “do.” But people learn that they must develop their hearing when they enter a wide variety of occupations and activities. I investigate some of the strategies and techniques for working on competent hearing, taking as my focus the fields of medicine, music, outdoor adventuring, and Morse code operation. The four studies show that hearing is considerably more varied than we often assume. In examining what it takes to become competent, the book explodes myths of genius, natural talent, or the idea that certain skills are the province of particular kinds of people. Overcoming the social distance between insiders and outsiders requires access to the collectively supported ways that seemingly natural sense abilities are cultivated to competency.

Readers can approach this book in different ways. If you are particularly interested in musicians or mountaineering, then you might like to sink your teeth into the world of your choosing first. One of the strengths of the book is its comparative look at the strategies for cultivating the ear. Having read about hearing in one case, you might find yourself gripped by the ways in which it is cultivated and done elsewhere. If you start at the beginning, you will be first introduced to the idea that our senses are specialised and the story of the project. You will then read about doctors, musicians, outdoor adventurers, and Morse code operation. The final chapter grapples with where this study sits within multiple traditions of philosophy and social theory.

The wide angle

This book is part of a much longer project within philosophy and social theory seeking to understand what I describe as the sensed unconscious. The concept describes aspects of our embodied experience that remain concealed from our reflective attention as we orient outward. For example, in social interaction, we can often be self-conscious of how we will appear to others, but we are mostly unaware of how we are using our bodies to shape others’ perceptions of us. In a similar way, Michael Polanyi wrote about how we cannot focus on the movement of our tongues as we speak, because doing so would compromise our ability to focus on the meaning of our words. Much of the work that has grappled with these aspects of experience that are “in” the body and yet disattended has done so through the lens of habit, or the habitus. We acquire our dispositions, but once learned, they recede from our conscious attention.

I came to this topic due to an interest in the cultivation of different ways of perceiving. I trained as a classical pianist originally. As teenagers are want to do, I found myself drawn to metal and industrial music in an act of rebellion. People who knew me as a pianist could not comprehend this. How could I be listening to this with my “highly skilled ears”, the inference being that I should know better. I had a hunch that they were not making the same sense of the music as me. And I didn’t think this was a matter of “taste”. I became interested in how our ways of perceiving developed. I didn’t just want to understand how our bodies are a resource in social action. I wanted to know where these bodies came from. Many scholars dealing with these ideas paid less attention to the ways that we can turn to how we work our bodies. My book contributes to this project.

A close-up

One of the remarkable observations detailed in this book is how hearing involves more than the ear. Our senses operate in such a way that there is an intertwining between what we typically conceive of as isolated senses. In educational settings, teachers often support students to shift how they hear by getting them to focus on a different sensory cue. I sat with an orthopaedic surgeon who was teaching me about the significance of the “creaks” and “grates” that signify arthritis. He said he listens for them as patients walk into his consulting rooms. This is not something that he learnt about in medical school. It came from his sensitivity to the sounds that happened as patients moved their joints when he was examining them. He was treating me like a medical student to get me to understand this. He got me to place my hand on his knee as he moved the joint to extend his leg. He asked me not whether I could feel the grates or grinds, but instead: “Can you hear that?” I couldn’t on the first go—these ways of sensing and knowing do not come quickly. We repeated the exercise.

In cases like medical practice, it is okay for an action to be repeated as the clinician works to perceive the sound. The case of music making is radically different in this sense, in that musicians need to “hear” themselves before the music sounds. They need to focus on organizing their bodies to form the sound that will be heard if they move this way or that. Musicians necessarily focus on what other sensory cues offer, whether that is glances between musicians to signal an entry point, or collective attention to the rhythmic pulse. One of the most vital strategies is hearing via proprioception, or our inner sense of our body positions and self-movement. Among the stories of proprioception is one from a cellist who knows her sound before it comes out of the instrument based on her sense of her body from within.

Lastly

There has been great interest in recent years in the nature of decision-making, especially among experts operating in contexts in which there is a degree of time pressure. Authors who have grappled with this often refer to the power of intuition and tacit knowledge. Sometimes they refer to the deep well of experience on which people act, without thinking about it. It is my hope that this book shows readers that we cannot take intuition and tacit knowledge for granted. It is something that individuals and communities actively cultivate. With this in mind, we need to have continuing strong systems for supporting this knowledge development, at a moment in time in which it is the quick wins that follow from using artificial intelligence technologies that are taking centre stage.

.jpg)