Heather Hendershot Nashville Bloomsbury, British Film Institute, 104 pages, 5 x 7 inches, ISBN 978-1839028946

In a nutshell

This book is about Robert Altman's 1975 film Nashville, which is a quintessential 1975 film, but also relevant for the present moment of political cynicism, polarization, and violence. While the movie is about interpersonal relationships, its undercurrent deals with the fallout from Watergate, Vietnam, and very specifically, Nixon. The film started shooting on July 4th, 1974 – perfect timing. When they started filming, the Watergate hearings were underway—in fact, being broadcast on TV—and Nixon resigned in the course of the production. So, that political feeling is always there, even though the movie is also about the less overtly political issue of how people treat each other and the foibles of human relationships. Nashville is implicitly tackling the fallout from Vietnam, and everything that happened in 1968 – violence in the streets, the Chicago Democratic National Convention, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, and the assassination of Martin Luther King. It is a very human film that doesn't seem like a political film in the way that a documentary would, but to my mind, being informed by that politics helps you understand the film and what it has to say about America.

The first and last paragraphs of the book are very precisely the frame for what I'm doing – the whole book in a nutshell. I’d rather people read it from cover to cover, but if you read the first and the last paragraph, you would really have a sense of the importance of the film, and of my feelings about it as a political text, but also as a work very much about human relationships.

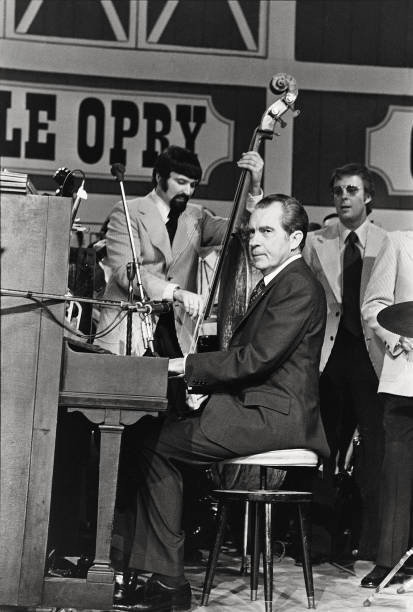

Nixon sitting at the piano at the Grand Ole Opry in 1974.

Getty Images

The wide angle

I write about the politics of media –right-wing and conservative media, mainstream network television news, and journalism history. My era is the 60s and 70s, and the Nashville book is exactly at this focal point. My earlier books do a deep dive into large amounts of content, such as Cold War right-wing broadcasting, or William F. Buckley's TV show Firing Line which ran from 1966 to 1999, totaling over fifteen-hundred episodes. My book When the News Broke is about network coverage of the infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention, which meant looking at hundreds of hours of TV.

In the Nashville book, by contrast, I was able to hone in on a single film and really dive into it, performing a microanalysis. So I have the big political picture as a frame, but I also have the little picture, the film itself, to narrow in on.

The book is in three parts. The first sets up the context of 70s filmmaking, an era that many scholars consider a golden age of American cinema. I call it a cinema of losers. The protagonists of the New Hollywood are really sad guys – almost always guys—who are dealing with anxiety and despair in a really dark register that feels far from the Hollywood studio era of filmmaking, where moral absolutism was more common.

The second chapter of the book is about Robert Altman's history and contextualizes where Nashville falls in that history. Understanding what he did before helps us understand the film, to some extent. His next picture after Nashville is Three Women, a really strong film about women and their interpersonal relationships.

Nashville stands out within Altman's work, and also within the context of 70s cinema, for really dealing with women, their relationships, and their issues. One thing I emphasize is how women contend with heterosexual relationships, how they are poorly treated, and how they have agency within these difficult scenarios or don't. Also, I discuss the power relationships between men and women, and between women and women. There is a sort of a pecking order on display in the film. For example, you've got a big country Western star, Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakely) and you've got a slightly lesser star Connie White (Karen Black), and they are competitors. You can see their raw dynamics, even though they never appear together in the same scene.

The third chapter centers on Nashville itself. And I take it day by day, over the course of the film’s five days.

Should people read the book before watching the film or vice versa?

This book could be read before or after screening the film for the first time, and there are pros and cons of both approaches. It's a difficult film to follow the first time. It runs 2 hours and 40 minutes, with 24 characters, some of them underdeveloped. It doesn't have a typical strong, narrative plotline of, like ‘here is a hero trying to overcome or achieve goals’, or ‘this couple falls in love, and they break up, and then they get back together’. There are very standard formulas out there. Nashville is not that.

Some strong, smart films of the New Hollywood era, like, Dog Day Afternoon or Serpico or Scarecrow fit into genre classifications such as heist movie, crime drama, or road movie, and this helps us make sense of them. But Nashville, doesn't clearly fit into a genre, which is one thing that makes it a difficult film. So some people would benefit from reading the book first, because they would get the context and tools to understand what's going on.

On the other hand, I'm certain Altman would prefer someone watch the movie first. Part of the point of the film is to throw you in the middle of all of it, and to just ask you to rise to the challenge. Just hang out with this film, and try to figure it out. And if you don't know at the end what to think of it, Altman would say, ‘well, just go watch it again’. He didn't think that most of his films could be understood by watching them once. I'm sure there are other directors who feel that way, but they don't always say that, because it's not popular. Producers don't want to hear ‘people have to see my movie two or three times to really get it’. Most people don't go back to the theater over and over again. Especially back when theatrical viewing was the dominant norm. In 1975 it wasn't about home viewing.

Altman was of the mindset that people go back to art museums, and they look at the same pieces of art over and over again. People listen to record albums over and over again. Why not watch a film more than once to figure it out? So, in a perfect world, newcomers to this film would watch it 3 times in a row. Most people won’t do that. One alternative approach is ‘watch the film, feel a bit overwhelmed, be unsure of what it means, and just think about how it makes you feel’. It has a very dramatic, difficult ending that leaves people a little bit in shock. I have been in audiences watching it where half the audience has never seen it before, and you hear people gasp at the end.

I'm very keen in my daily life – not my writing life – to not give away spoilers, but obviously, if you read the book, you'll know exactly what is going to happen in the film. I think seeing it without knowing that will make for a more emotionally and intellectually moving, challenging, and complex experience.

The close-up

The cover of the book is truly beautiful. I was very happy with the press, and I had some creative input on the work that their wonderful designer did. I emphasized that I wanted all women on the cover, and I wanted it to include Sueleen Gay, the character on the right of the cover, who is poorly treated in the film. It's easy not to notice her at the end of the picture, because there’s a big panoramic shot, and she's just a little figure off on the side, but she's been amped up for the cover, which is very striking. It might not make sense, though, if you haven't seen the film.

For people looking at this book in a bookstore, flipping through, they will see the images first. It's richly illustrated with a lot of color and a number of black-and-whites. I asked two people for their reactions, one who knew the film pretty well, and one who'd never seen the film. The person who already knew the movie but hadn't seen it in a while was excited to read the book and rewatch the movie, and the first thing he noticed flipping through the pages was that I had provided a chart of all the characters.

A chart can be a boring thing to a lot of readers, but my book was written for cinephiles and a broader audience, and the chart is not dry. It gives my perspective on the characters and raises a few questions. For example, one character, L.A. Joan, played by the late, great, Shelley Duvall, floats through the movie in changing outfits. She picks up a lot of men, she doesn't have that many lines, she's a kind of mysterious character in some ways, and I ask in the chart, ‘is she wildly confident or wildly insecure?’ Because you can't tell! And that's a helpful prompt to think about.

The other person, who was new to the film, was really drawn to two images. One was Nixon sitting at the piano at the Grand Ole Opry in 1974 – the same stage where they shot a big scene in the film a few months later. This is the grand opening of the brand new Grand Ole Opry building, where country western singers perform all the time down in Nashville. Nixon is sitting at the piano playing, and he looks so phony – like a terrible piano player. He looks insincere while trying to look sincere because he's courting the country western market. Now, there is a character in the film who is modeled after Nixon operatives, and at one point in the film he refers to ‘country crapola,’ denigrating the market of voters that he's there to woo. He obviously doesn't respect them, and that is what Nixon was doing at the time, wooing the country western crowd by going to the Opry.

So, this younger person who did not know about the film and was not deeply versed in 70s cinema, was like ‘wow, that photo of Nixon is striking and hilarious!’. And then he immediately flipped to a second photo of Nixon, a staged shot where Nixon is trying to show that he is a cool, relaxed person who just happens to be taking a walk on the beach. Obviously, he’s trying to craft his image to convey that he is not the paranoid and vindictive person that he actually was. Rather, he is a happy, relaxed fellow who wears a windbreaker to take a stroll. This photo op totally fails because he is wearing dress shoes, and he is really awkward. He didn't wear his usual tie, but he's almost an animatronic robot down there walking in his wingtips. So the new reader honed right in on those two images and was intrigued. He got the point: ‘The book is political. There is humor in the book, because these pictures are funny, but there is something serious going on’, because we know ultimately what happened with Nixon was very serious.

Lastly

There is a coda following the third chapter that I hope will resonate strongly with readers. It is about the political moment we are in, and how we need to keep it together. We need to keep going and find hope, rather than falling into despair or apathy. That said, we can’t be Pollyanna-ish and overly optimistic about how we are going to fix our authoritarianism problem and dig ourselves out of the very dark moment we are living in. Of course, a movie from 1975 is not going to fix that, but that doesn’t mean it’s not relevant. Altman was concerned about interpersonal relationships, apathy, and empathy. Throughout many of his films, he confronts the fact that people often treat each other poorly. But he hasn't given up hope. At one point in an interview, he describes himself as someone in the desert, but he has an umbrella. You are in the desert. It's very unlikely that it's going to rain. But having the umbrella shows that you still have some hope. You are not an optimist, but you have not given up. Even though within the film characters treat each other poorly, they have certain moments where they kind of get it right and have brief moments of connection.

If 10% of our lives include brief connections and 90% don't go so well, we have to really lean into the value of that 10% where we do make the connection. Nashville is in its own way a radical call for empathy – something we need now more than ever.

.jpg)

.jpg)