Mathew, Shaj The Dialectic of Cosmopolitan Time Oxford University Press, 200 pages, 6 x 9 inches, ISBN: 9780197819074

In a nutshell.

The book asks not where the Global South is—a fair question in its own right—but when it is.

After the colonial era, many postcolonial writers felt an acute sense of belatedness. They considered the “true present” to be somewhere else—namely, in Europe. If these writers felt behind the times, postcolonial theorists responded to their supposed time lag with a simple theoretical gesture: they asserted that their nations experienced the same “now” as Europe did. They advocated for equality in terms of time.

In the wake of decolonial turn, however, some theorists began to question the desire for temporal parity. Why should postcolonial nations even want to share the same “now” as their former colonial oppressors? This line of thought produced one enduring consequence: a fetish of the precolonial past and a return to “tradition.” These traditions, real or “invented” as Eric Hobsbawm once put it, would excavate indigenous values, languages, and concepts. They would also avoid standardizing European time as universal. Today, returns to tradition are very much in the zeitgeist—on the left and the right, in both the Global North and the Global South. Tradition manifests itself in the concept of indigeneity on the left, while it surfaces in right-wing nostalgia for authentic cultural values. Both retreats into the past are products of the present. Returns to tradition, what’s more, almost always lead to nativism and nationalism. That’s why this book seeks to reinvigorate the term cosmopolitanism instead.

A cosmopolitan sense of time, I suggest, avoids the siren song of tradition, as well as the earlier desire to simply assimilate into European time. In this way, cosmopolitanism’s tagline—coexistence—gets a new dimension. Instead of the coexistence of religions, cultures, or languages, we get the coexistence of contradictory times. Religious and secular, revolutionary and reactionary, linear and non-linear—these discrepant forms of temporality give each other meaning.

The Wide Angle

The first two words of the book are Edward Said. His body of work continues to inspire debate within postcolonial studies almost 50 years after the publication of his 1978 hit, Orientalism. I’m less interested in that specific text than in the misunderstandings or scholarly lacunae it generated. (A focus on Orientalism also obscures his incredible range, which included classical music.) Thinkers such as Hamid Dabashi, Dipesh Chakrabarty, Vivek Chibber, and Wael Hallaq have helped me think through Said’s critical afterlife.

Beyond postcolonial studies, the book taps into the amazingly rich scholarship on “time” across cultures: I’m thinking of On Barak’s On Time; Vanessa Ogle’s The Global Transformation of Time; Avner Wishnitzer’s Reading Clocks, Alla Turca; Mark Rifkin’s Beyond Settler Time; and a modernist classic, Henri Bergson’s Time and Free Will.

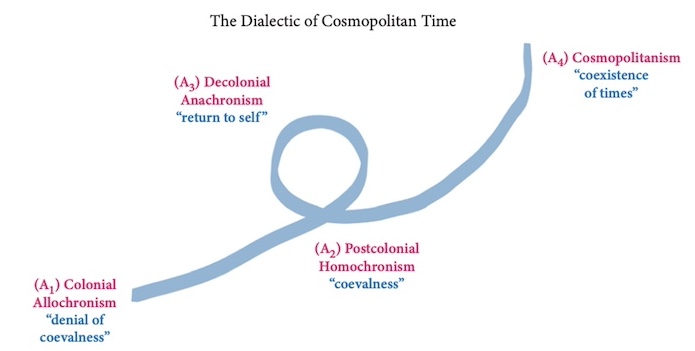

More pertinent to the book’s argument, however, is Johannes Fabian’s Time and the Other. Fabian advances Said’s more geographic argument about the Orient and Occident in terms of time. For Fabian, anthropology locates its (initially non-European) object of study in a more primitive time. He deems the temporal predicament of non-European cultures “allochronism”—the Greek “allo” denotes their supposedly “other,” belated, or backward location in time. The dialectic of my book’s title points to a journey in which theorists of the postcolonial or non-European world try to find a way out of allochronism, or this supposedly more primitive stage of history. Postcolonial theorists first opted for homochronism, arguing that all cultures occupy the same slice of time, while decolonial theorists subsequently elected for anachronism, a term which evokes the (literally) backward-looking fantasies of the past that surface today and dictate our political landscape. Unconvinced by the solutions of homochronism and anachronism, my book culminates in a defense of cosmopolitanism. This word already has a meaning—world citizenship—but the book reimagines its tagline: coexistence. The coexistence it imagines is one of temporality.

The project of temporal coexistence sheds light on the spirit of our own times. In the present conjuncture, invented traditions proliferate day by day. The book models a way for these discrepant tempos—antiquity and modernity, universal and local time, qualitative and quantitative—to coexist.

The four stages of the dialectic

A close-up

The book looks to modern and contemporary literature and film from Turkey and Iran. The chapters examine the temporalities of the late Iranian auteur Abbas Kiarostami and the Turkish Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk. They interpret other Middle Eastern modernist writers including the poets Forough Farrokhzad and Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, as well as the Ottoman novelist Ahmet Midhat Efendi.

The book also asks how we tell the politics of history, using the Louvre Abu Dhabi as a case study. That chapter addresses a problem that’s emerged in the field of comparative literature: once we add non-European sources to our canons, how do we integrate those languages and cultures into the same world history? Should we, in fact, incorporate European and non-European sources into the same timeline? Or does imposing European timelines (“Eurochronology”) onto non-European subjects do violence to these texts and the histories and calendars that produced them? Do certain eras of world history—such as that of modernity—welcome a single global timeline, given the interconnectedness imposed by colonialism and capitalism? And do earlier eras, such as the medieval era Before European Hegemony that Janet Abu Lughod describes, reject such interconnectedness, instead welcoming a multiplicity of culturally specific timelines? These are the political and historical stakes that the museum poses in Chapter 5.

Lastly

The book closes with my translation of Ahmet Haşim’s “Muslim Time” (1921). In November 2023, I stumbled upon a snippet of the Turkish text at the Pera Museum in Istanbul. As soon as I saw it, I knew I had to translate it. It perfectly encapsulates the book’s main argument. In it, Haşim describes the intrusion of “alafranga” or European time into Turkey. (He calls it a “siege”!) This alafranga time, synonymous with the 24-hour clock, interrupted the “alaturka” rhythms that previously organized Ottoman life. Those rhythms corresponded to sunrise, sunset, and the five calls to prayer.

The book arrives at a timely moment. Whether it’s the meme that encourages us, however facetiously, to “reject modernity, embrace tradition” or “return” to the past; the debate about the origins of the United States (1619 or 1776?); the anxiety about the future of the climate or world order; or the revanchist global right—the present convenes a war about the meaning of the past, present, and future. Maybe framing these colliding temporalities, and the ideological worldviews they represent, through the concept of cosmopolitan time can help us to better understand, and ultimately, overcome, the impasse in time society finds itself in. That’s my hope.