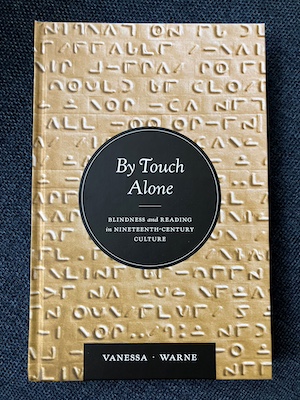

By Touch Alone explores the experiences of the first generations of blind people who learned to read by touch. Exploring the reading lives of English-speaking blind people and the material history of the raised-print books they read, it documents the many ways in which reading by touch shaped nineteenth-century culture. While reading by touch transformed the lives of many blind people, changing their experiences of education, leisure, faith, social connection, and privacy, reading by touch also had impacts on nonblind people. Sighted observers of this new way of reading were, for example, prompted by the entry into literacy of blind people to reevaluate not only their beliefs about blindness but also their understanding of what it means to read. To put this differently, the advent of reading by touch challenged existing ideas about the relationship between books and the bodies of their readers. Books made for and by the first generations of blind readers broke with many long-established conventions of book design. In addition to replacing inked text with embossed text, these books were differentiated from the books of the sighted majority by their dimensions and bulk, by the arrangement of text on the page, and by their experimentation with script systems different from the Roman alphabet.As I explore in my book, by the middle of the nineteenth century, more than twenty different script systems had been proposed for use in books for blind readers. Braille, the now near-universal script used by blind readers, only secured its present-day prominence by outlasting many rival scripts. Now obsolete, some of these rivals to Braille were based on the shapes of shorthand symbols, some were radically simplified versions of the Roman alphabet, while others rejected orthographic conventions. One raised-print script, invented by British blind person William Moon, broke from the traditional ordering of letters and words in written English. Preferring the boustrophedonic arrangement of words and the letters they contain, Moon published books that alternated line by line between a flow of text from left to right and a flow of text from right to left. Readers would move their fingers left to right across the first line of text and from right to left across the second line. To a sighted reader, the word “the” in the first line of text would appear as “eht” when it appeared in the second line of text. This experiment was one of many changes activists and innovators proposed with the goal of improving blind people’s reading lives. Like other changes, Moon’s arrangement of text challenged sighted people’s perception of their own reading practices as natural or superior. Perhaps unsurprisingly, some sighted commentators objected to innovations of this kind on the basis that they isolated blind and sighted people by differentiating the two groups’ written cultures. Some sighted commentators were so troubled by innovations of this kind that they described raised-print scripts as barbaric, foreign, and coded.

.jpeg)