One of my favorite moments in Douglass and Lincoln’s relationship was at Lincoln’s second inaugural, when they met for the last time. It was as though in four years, the world had been turned upside down. After all, after Lincoln’s first inaugural, Douglass had been so fed up that he called the president the greatest obstacle to freedom in America and a representative racist. In fact, he had made plans to emigrate to Haiti. But then the war intervened, opening the way to destroy slavery, and so Douglass had abandoned his plans to move to Haiti. Now, on March 4, 1865, the mood in Washington was celebratory. The war was almost over; 170,000 blacks were in uniform, marching triumphantly across the South; and Congress had recently passed the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery throughout the United States.The day was bleak and rainy.

Mud covered the unpaved streets and people “streamed around the Capitol in most wretched plight.” Many of them had been up all night, having taken special inaugural trains that arrived in Washington that morning. Between the cinder dust from trains and the mud and rain, the thirty thousand people attending the ceremony looked gray and worn out. “Crinoline was smashed, skirts bedaubed, and moiré antique, velvet, laces and such dry goods were streaked with mud from end to end.”

The ceremony was “wonderfully quiet, earnest, and solemn,” Douglass noted. There was a “leaden stillness about the crowd” as Lincoln delivered his address, and Douglass thought it sounded more like a sermon than a state paper.In his speech Lincoln emphasizes God’s inscrutability. “Both sides read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other.”

He imagines a wrathful God wreaking vengeance against slaveholders but carefully avoids presuming to know God’s will. Such presumption would be hubris, he implies. “The Almighty has His own purposes.” The proper attitude toward people and nations should be one of humility, tolerance, and forgiveness. “With malice toward none; with charity toward all.”

After the ceremony Douglass went to the reception at the White House. As he was about to enter, two policemen rudely yanked him away and told him that no persons of color were allowed to enter. Douglass said there must be some mistake, for no such order could have come from the president. The police refused to yield, until Douglass sent word to Lincoln that he was being detained at the door.Douglass found the president in the elegant East Room, standing “like a mountain pine in his grand simplicity and homely beauty.”“

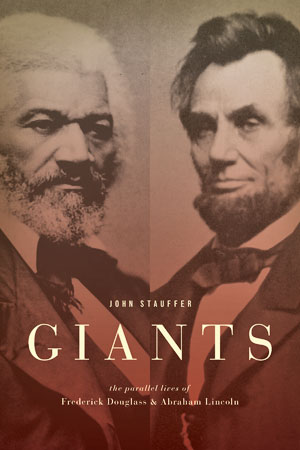

Here comes my friend,” Lincoln said, and took Douglass by the hand. “I am glad to see you. I saw you in the crowd today, listening to my inaugural address.” He asked Douglass how he liked it, adding, “there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours.”“Mr. Lincoln, that was a sacred effort,” Douglass said.I wrote GIANTS during a propitious time: Barack Obama’s The Audacity of Hope became a bestseller and then of course Obama ran for and was elected president.

Fittingly, GIANTS was published on election day. And Lincoln’s bicentennial is in 2009.Obama’s journey, like Douglass’s and Lincoln’s, has been nothing short of breathtaking. It is not coincidental that Obama knows Douglass and Lincoln better than many scholars. He has steeped himself in their writings and has been deeply influenced by them. From Douglass he understands that artists, whether as writers, orators, or politicians, can break down racial barriers; and Douglass also taught him that power concedes nothing without a fight. From Lincoln, Obama has learned how to gauge public opinion and to reach beyond social divisions for common understanding.

And from both men Obama has learned how to use words as weapons that can inspire and transform a nation.Writing the book has thus given me a much better understanding of our own time. We carry the past within us and are unconsciously shaped by it, to paraphrase James Baldwin. In certain respects, the Civil War is not over; we are still fighting about the meanings of America on cultural and political fronts. Indeed, while steeped in the writings of Lincoln and Douglass, and sometimes dreaming of them, I found myself quoting Faulkner’s famous maxim, “The past is not dead. It’s not even past.”

GIANTS reveals two legacies of Douglass and Lincoln for our own time. One is the Obama phenomenon. The book enables us to understand how Obama rose up from poor black kid to president. Indeed, without Douglass and Lincoln, Obama never could have become president. The other legacy is as inspiration: Douglass and Lincoln call on us to bind up the nation’s wounds and to fulfill the ideals of freedom and equality of opportunity for all. They inspire us to be audaciously hopeful.