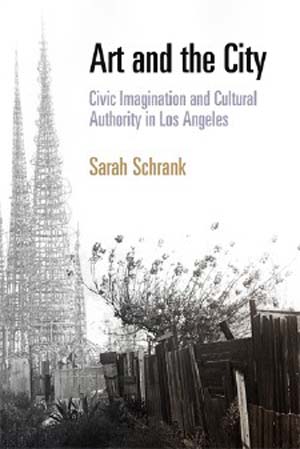

I encourage readers to explore the many art controversies explored in Art and the City as windows onto the urban landscape at specific historical moments. The chapter on the Watts Towers, for example, beginning on page 135, describes a most remarkable artwork, also depicted on the book’s cover—seven towers of steel, cement, glass, and found objects that Sabato Rodia, an Italian immigrant, built in his backyard between 1921 and 1954. Standing almost 100 feet high at their highest point, the Watts Towers were a private project meant for the public gaze. Surviving two violent urban uprisings in 1965 and 1992, and standing in one of the poorest parts of Los Angeles, they are probably the city’s most famous artwork. The chapter describes the grassroots efforts of a broad-based arts community to save the Watts Towers when the city tried to tear them down in the late 1950s. After this victory, activists established a center to teach kids art and music, a facility that remains in Watts to this day. For all of the intricate on-the-ground politics involved in protecting and maintaining the Watts Towers, their story is also one germane to students of American popular culture. Hollywood movies, record companies, and advertisers have frequently featured the Watts Towers as a symbol of black Los Angeles, a cultural trope that challenges historical and mainstream representations of the city. The history of the Watts Towers perfectly captures the diverse and unexpected struggles for cultural representation I describe throughout Art and the City.Sometimes the most valuable public art is that which seems to fight itself. Estrada Courts, a public housing project in East Los Angeles, grew famous for dozens of murals painted in the 1970s. Directed by professional artists, the young residents of Estrada Courts, many of whom were members of a local street gang, painted huge and colorful murals with a range of historic and political themes. There was much public acclaim from across the country, even from Gerald Ford, then President of the United States. Nevertheless, many of the same kids who had painted the murals soon began tagging the walls with gang graffiti—what their murals were meant to cover. Rather than vandalism, these acts demonstrate a complex sense of wall ownership and a social tension created by the discomfort of official attention and acclaim.Art is not just something that people hang on their walls to match a piece of furniture or a multi-million dollar status symbol hung in a museum or plopped in front of a corporation’s main administration building. In cities, public art is frequently a controversial way for the powerful to exert their power and for the powerless to have a voice. We have to understand public art as part of an ongoing civic conversation, not simply the mass of a sculpture in the middle of a plaza.