The book can be read like parts of a puzzle. Although some themes (education, history, progress, and national identity) permeate the entire book, one can start anywhere depending on one’s interests—be those philosophy, the legacy of the monarchy or the Revolution, protectionism or colonialism, high art or popular entertainment, Wagner or the French avant-garde.I’d recommend starting with the walking tour of Paris, for experiencing the city is like an overture to its music. The city’s grandeur, like much of the music, keeps alive memory of past greatness and testifies to the importance many French ascribe to history and what they share as a people. The urban environment attests to the overwhelming nature of state power in France, yet any promenade in the city invites us to acknowledge the fleeting as well as the durable aspects of culture, popular as well as elite expression, and to find meaning in both. The structure of Paris — its grand vistas, monuments, and bridges alongside its charming cafés, sinuous alleys, and hidden-away treasures — suggests a model for thinking about the structure of the musical world. It also encourages us to think about the kinds of networks music needs to thrive, and the sense of national fraternity as well as personal empowerment to which music can contribute.

Chapter 3 explores music’s contribution to republicans’ most pressing need, forming individuals who could think as well as act like citizens. Music not only teaches skills and serves as outlets for personal expression, contributing to people’s self-discipline and self-esteem; it also provides opportunities to learn judgment, a critical aspect of citizenship. Listening could involve rational processes like discrimination and empirical comparison and call on the imagination for the interpretation of meaning. Learning critical judgment through making comparisons, distinguishing aesthetic differences, evaluating their meaning, and forming opinions, connects art to politics, active listening to active citizenship.

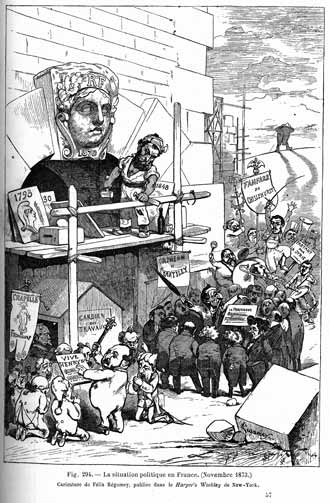

This kind of listening became particularly valuable in concerts that juxtaposed la musique ancienne et moderne. By suggesting the relevance of both Revolution and the Ancien Régime to the present, these concerts offered listeners a means of confronting their political differences as well as any underlying ambiguities, ironies, and paradoxes. They also gave listeners opportunities to see value in conflicting ideals and provided arguments for tolerance and reconciliation over the nature of French identity.

Chapter 8 begins with a description of a particular performance. To prepare for a concert its employees offered to friends, family, and customers on 28 November 1885, the Bon Marché department store cleared out the merchandise on its main floor and installed a platform for 400 performers at one end of it. The date was chosen to coincide with the exhibition of new coats just before the end-of-year sale. The concert itself was the fruit of the music courses the Bon Marché provided for its employees, showing them what could be gained from hard work and discipline. For this occasion, the organizers invited stars from the Opéra and the most popular café-concerts to perform between their choruses and wind-band fantasies, a practice begun in 1883. With art songs and operatic excerpts juxtaposed with comic ditties, and marches placed alongside romances, the result was eclectic in the extreme. In this sense, they resembled the experience of the city and its department stores. Since Bon Marché employees typically performed in at least half the works put on in the store’s concerts, performance was a way of mediating class and cultural differences among professionals and amateurs and among rich and poor on stage and in the audience.

For too long, historians have left music out of their stories, and, in doing so, they have left out an important part of who we are as individuals and members of society. Musicologists, seeking to elevate music to the highest of the arts, have often looked to German idealism as a way to understand music’s value. Composing the Citizen challenges both positions. As the current French Minister of Culture described the worldwide in 2006, music has the power to “foster self-knowledge and the formation of groups” and to “reconcile the imaginary and the political through musical performance.”

Such were also republican ideals. But rather than concentrate on ideology or public policy, I examine the circumstances underlying specific performances and the contingencies of meaning tied to specific moments, as might an ethnographer. It is in these contexts, I argue, that music helped the French come to grips with not only their political and social differences, but also with their identity as a hybrid people, the product of both assimilation and resistance. By the end of the book, French culture emerges as an important model for national identity—not as homogeneous, but as complex and dynamic.As such, French culture is an alternative to both the ethnic model of identity found in Germany and Japan and that based on shared philosophical ideals such as in the United States.

This is particularly valuable in today’s world. If there is coherence in the French nation, it derives from both a certain sense of the public interest—that which anything of public utility serves—and shared culture.As differences of class increase in our globally interconnected, finance-driven world and as religious practices drive deepening wedges in our societies, this book reminds us that music’s broad accessibility makes it possible to create dialogue, as it did between monarchists and republicans in the late 19th century. Music helps to establish community, the social bond that makes it possible for humans to live together. With Composing the Citizen, I suggest what we in the twentieth-first century can learn from this Republic and its music, not only people struggling in emerging democracies, but also those living in the most modern of cultures.