The fourth chapter, “Consuming: The Palace Bridal Chamber” perhaps best illustrates the larger arguments and tensions at this book’s heart.This chapter initially grew out of my interest in honeymoon suites—I grew up in Niagara Falls. Honeymoon hotels seemed normal, if naughty, to me growing up in the 1970s.

But when I moved to England to study architectural history, they became increasingly surreal. And with good reason! Honeymoon hotels are incredibly peculiar – both in the sense of being particular (dedicated honeymoon hotels in Europe are almost non-existent) and unusual in an American context (if we buy into the idea that Americans have historically been puritanical or, at least, modest in sexual matters.) So how do we account for the growth of entire resorts devoted to newlywed sex?Honeymoon suites first appeared in the 1840s on Hudson River palace steamboats.

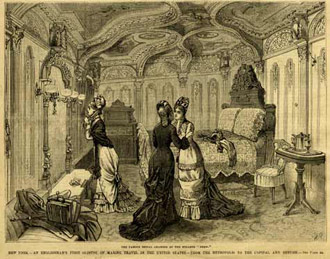

From there, they were quickly adopted by palace hotels in big urban centres, particularly those constructed in New York in advance of the 1853 Crystal Palace exhibition. Honeymoon suites, then known as bridal chambers, were amazing productions: prominently positioned, lavishly decorated, and subject to endless public scrutiny.

Thousands of visitors toured them physically, thanks to captain’s tours and hotel opening days, and virtually, in media articles that microscopically noted every feature from carpets to bedspreads.While I had read my Foucault and did not subscribe to the myth of Victorian sexual repression, I was still unprepared for the sheer publicness and exuberance of these rooms.

They flew in the face of the idea that the act of sexual consummation should be discrete and hidden. Rather, along with other emerging sentimental rituals like Christmas, they made it seem right and proper that significant life events be celebrated with extravagant acts of consumerism and promoted an idealized image of conjugal love in which sex and goods intermingled. The feminized appearance of the chamber also underscores that this vision of love and luxury was highly gendered.

These were bridal chambers after all: their elaborately layered white interiors resembled nothing so much as a bride’s gown, and served to remind spectators of the act of bridal “unwrapping” that would later take place.But bridal chambers didn’t simply represent the triumph of consumerism; rather, they mark a turning point in my history. The decadence of bridal chambers, along with their mirror resemblance to the upper-class brothels nearby, forced nineteenth-century social commentators to seriously weigh up the effects of America’s expanding wedding culture and its relentless focus on the bride.

They didn’t like what they saw – but sensation writers identified something even darker. In George Lippard’s The Quaker City (1845) and George Thompson’s The Bridal Chamber and Its Mysteries (1855), bridal chambers emerge as places where sentiment was faked, love deceived, and virtue lost.For Lippard in particular, the bridal chamber confirmed the corruption of sentimentalism itself, a system which, he believed, kept women in sexual slavery.

His is as powerful an indictment of romance as any made by radical feminists in the 1970s – and one suspects that the twentieth-century honeymoon suite, complete with heart-shaped whirlpool baths and Playboy-inspired décor, would not have changed his mind.

There is a growing body of scholarly literature on sentimentalism, weddings, matrimony, and the rituals/invented traditions that surround them. While I enjoy and have learned from many of these books, I am sometimes frustrated by their tendency to view practices like honeymoons simply as the repressive tools of patriarchy and capitalism.Honeymoons certainly do represent society’s dominant values – sentimentalism, consumerism, patriotism, heterosexism etc.

But to treat honeymoons as straightforward celebrations of these values is to ignore the contradictions and conflicts that dogged their practice or, more to the point, emerged through their practice. Honeymoons were shaped and re-shaped over the course of the nineteenth century.It seems important to me that we hang on to the messiness of nineteenth-century honeymoon practice and that we don’t try to tidy it up too much – that is, impose an ideological coherence onto it that the practice itself never had.

Otherwise we would wrongly suggest that the “triumph” of the lavish white wedding was historically inevitable (hence irreversible) and that it always means the same thing to all its participants and its audiences. It also leaves us poorly equipped to explain contemporary Niagara Falls’s newfound popularity as a site for gay weddingmoons.

As this example proves, practices like honeymooning can serve as vehicles through which non-dominant groups make claims to social legitimacy and belonging.Although I still feel ambivalent about many aspects of white weddings (their cost, their wastefulness, their symbolic exchange of women), their very openness to appropriation – their ability to undermine those values they seem to so obviously represent – seems like a valuable and positive takeaway from their history.