The recent earthquake in Haiti echoed—on a much larger scale—the events of Hurricane Katrina, provoking a depressingly familiar reaction from the authorities responsible for militarizing or “securitizing” relief efforts.

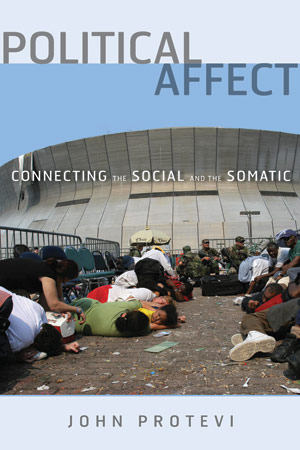

In Chapter 7 of Political Affect, I look at how a racialized fear contributed to the delay in government rescue efforts in Hurricane Katrina until sufficient military force could confront thousands of black people in New Orleans; the government's racialized fear flew in the face of the massive empathy of ordinary citizens, a communal solidarity that lead them to rescue their friends, neighbors, and simple strangers until they were forced to stop by government order.

The Katrina chapter has the widest angle of approach of the three case studies. Deleuze’s ontology of self-organizing material systems not only uses the same concepts to think about natural and social systems, it thereby shows how they can interact. I begin the chapter with a study of the “elemental” factors of the hurricane event. I first examine the land and the river to examine the precarious state of Louisiana’s coast. Flood-proofing the Mississippi river has starved the bayous of their annual dose of rich alluvial sediments, while navigation channels for oil company boats have introduced salt water far into the wetlands, upsetting the balance required for their growth and maintenance.

I then look at the sun, the wind, and the sea in the formation of hurricanes as meteorological systems. These natural factors of the earth’s thermal regulation system are also key factors in Louisiana’s history: the trade winds and Gulf Stream enabled the Atlantic triangular trade system, while sugar (a bio-usable form of solar energy) was a key crop in both Saint Domingue/Haiti and Louisiana.

Next, I examine the role a racialized fear of a black slave uprising has played in Louisiana history, especially the Pointe Coupee conspiracy trial of 1795. At the height of both the Haitian and French Revolutions, a group of black slaves and poor whites conspired to rebel against the white power structure. The conspiracy unraveled, but only the blacks were put on trial, effectively turning a Jacobin political revolt into a racialized revenge fantasy.

The book then briefly reviews recent affective neuroscience evidence of increased amygdala action in racial perception; I speculate as to the racial undertones of the decision to stop the spontaneous rescue effort. In particular, I look at the rumors of shots at rescue helicopters and the subsequent echo of the “Black Hawk Down” episode in Somalia, as well as the rumors of black men sexually assaulting “tourists” (a code word for “whites”).

The political philosophy framework of the chapter comes out as I juxtapose the way in which pundits indulged a rhetoric of Hobbesian fantasy, when the reality was much more Rousseauean. In New Orleans, there was very little, if any, atomized anti-social predation; there was instead massive and spontaneous solidarity born out of empathy for threatened lives. If Hobbes was present at all in New Orleans, he was there beforehand in the atomizing practices of neoliberal capitalism, and afterward in the neoconservative militarization of rescue efforts. During the storm and the days of solidarity following it, he was absent.I hope that Political Affect will benefit both political philosophy and cognitive science by placing affective cognition in a political context. Cognitive science benefits by appreciating negative affects as well as the positive cognitive aspects of culture. It is true, as Andy Clark in particular has shown, that cultural forms and technological products can be “props” and “scaffolds” for our thinking. But not all cultural forms empower subjects. Depending on your developmental path, cultural practices can disempower you emotionally, just as they deny you access to heuristic resources. On the other hand, political philosophy benefits by stepping back from a focus on the rational subject and understanding how we sometimes respond to social triggers with decisions mediated by fear, anger, anxiety, and sadness; or even, at other times, with blind panic and rage.

Not all affects are negative, however, so we need to rethink human nature in terms of our capacity for love and empathy (what Aristotle would call philia). Theories of human nature are a political battleground, and we cannot be intimidated by the cheap cynicism and blustering scientism of the Right. For too long, the Left has adopted social constructivism to fight racist and sexist constructions of human nature. But in the meantime the neoliberal Right has distanced itself from old-fashioned racism and sexism to put forth a version of human nature as the individualist, competitive, utility-maximizing rational agent, an agent they claim is the result of natural selection in ultra-Darwinian competition.

But the neoliberals’ monopoly on biological discourse is overthrown by new research. We have to have the courage to claim that current evolutionary biology and developmental psychology show that human nature is prosocial in its default setting.Similarly, in their overreaching claim to be the inheritors of the classical liberals, neoliberals open the door to rehabilitating the theory of moral sentiments proposed by Adam Smith and David Hume. The political challenge of the new view of human nature is to extend the reach of prosocial impulses beyond the in-group, protect them from the negative emotions, and build on them to genuine altruism.All this is not to deny the selfish nature of the basic emotions of rage and fear. The key to a fruitful Left approach to human nature is the study of how such selfish, negative emotions are manipulated, or, more positively, how a social order can be constructed to minimize them and to maximize positive affects. I hope Political Affect can contribute to that project.