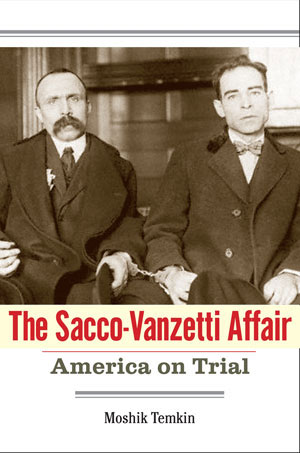

The end of chapter 2, pages 95-100, just before the book’s gallery of photos, deals with one of the biggest questions I faced when doing the research: why, in fact, were Sacco and Vanzetti executed?It was always assumed that the executions were just a follow-up to their convictions, and the two events, the conviction and the execution, were treated as almost one and the same. But six years passed between the time they were found guilty and the time they were led to the electric chair, and during that period a lot had happened—the entire context of the case had changed. Sacco and Vanzetti went from being anonymous anarchists who barely knew English to being international celebrities and, for some, even folk heroes (for others, they were dangerous terrorists, frauds, criminals, or all three). It wasn’t enough to say that they were executed because they had been found guilty; to execute them in 1927, at the height of the political storm that surrounded them, required a decision. I wanted to know how and why this decision was made.In this part of the book I try to answer these questions by telling the story of Georg Branting, a Stockholm attorney who visited the United States in the Spring of 1927 to investigate the case on behalf of “European opinion.” After meeting with many of the protagonists of the story, including Sacco and Vanzetti, Branting became convinced that the men were innocent, as they claimed all along, and that, because of this, the authorities would stop their execution. When that didn’t happen, he came to the grim conclusion that the international pressure exerted on the United States by Europeans, Latin Americans, and others around the world made many Americans in positions of power worry about appearing weak to the rest of the world. This was especially true of Massachusetts Governor Alvan Fuller, a man with presidential aspirations, who appointed a special advisory commission led by Harvard University President A. Lawrence Lowell, but who chose, at the moment of truth, not to pardon Sacco and Vanzetti. They were executed, in other words, for the same reason they became famous.This is part of why I argue in the book that, as opposed to what high school and college students read in their history textbooks, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed not in spite of the global protest but rather because of it. In this sense, I think the affair revealed a powerful division among Americans between those who viewed the U.S. as part of an international community, and those who insisted on its principled separateness from the rest of the world. Ironically, by the way, Fuller lost his political gamble, because the Republican Party, fearing to make the Sacco-Vanzetti case an issue in the 1928 presidential election, essentially sidelined him. By 1928 Fuller was out of politics and back at his business, selling automobiles.Sacco and Vanzetti left a number of odd legacies. A lot of people in the United States, Europe, and Latin America still recognize their names. I’ve seen or heard them mentioned in The Sopranos and Sports Illustrated, in novels by Kurt Vonnegut and Phillip Roth, in random conversations. The largest pencil-producing factory in Russia was named after them, and generations of Russian children associated the names Sacco and Vanzetti with the pencils and crayons they used. There was a film in Italy, a tango in Argentina, a song by Joan Baez and Ennio Morricone, a punk band in Germany, a brand of cigarettes in Uruguay. There are streets named after them in Italy and France. They often come up when people give examples of past injustices, or more facetiously, when people want to denote famous duos, as in Abbott and Costello, Jagger and Richards, Sacco and Vanzetti.I think all this reflects an uncertainty in how they are remembered. Sacco and Vanzetti do not have a clear place in our civic life or historical record. Part of the reason for this has to do with the fact that we still don’t know—and never will know—whether they “did it.”But in many ways, the Sacco-Vanzetti affair is still with us. Certainly the issues that animated it are very much alive. Americans today still do battle over the issue of immigration, and intolerance toward foreigners is still widespread, sometimes virulent, especially when times are hard. Europeans, Latin Americans, and other non-Americans are still concerned over, and in some cases outright hostile to, America’s presence in the world, and the way Americans handle international politics. And then as now, Americans are still divided over what was called, in Sacco and Vanzetti’s day, “foreign interference” in American affairs.Whether it is the death penalty, or the health care system, or how to deal with terrorism suspects, or even who should be elected U.S. president, non-Americans have and will continue to have opinions, because the United States is so powerful and what it does domestically reverberates externally. Many Americans bristle at this but many others welcome this. It depends on whether they see the United States as an entity separated in principle from the rest of the world, or as a genuine part of the world—a world in which Americans have a stake in the lives of non-Americans, and vice versa.This issue divided Americans when Sacco and Vanzetti were what one magazine called “the two most famous prisoners in the world,” and it still divides Americans today. This, I believe, is the context in which the Sacco-Vanzetti affair took place. My book is not an attempt to end the discussion about Sacco and Vanzetti, or to provide a definitive account. My aim was to start a new conversation, one that would not be about guilt or innocence but rather about the Sacco-Vanzetti affair—its significance and place in history.