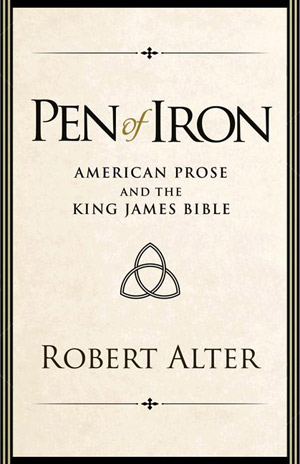

If I could look over the shoulder of a reader browsing through my book in a bookstore and whisper advice about how best to spend fifteen minutes of sampling the book, I would direct him or her to my discussion of Lincoln’s speeches in the first chapter.Though my book is about the American novel, not American oratory, I think the case of Lincoln, one of the great masters of style in nineteenth-century America, is illuminating. Lincoln, as most of us recall, was a self-taught man, having had only a couple of years of formal schooling. He was, of course, a genius, in writing as well as in political leadership. Like most literate Americans of his era, he had read the Bible—along with many very different things—in the King James Version, and he seems to have known it backward and forward.In my first chapter, I look at the astonishing things Lincoln does with the language of the Bible in his two greatest speeches, the Gettysburg Address and the Second Inaugural Address. Neither of these addresses is biblical through and through, but biblical elements play a crucial role in both—in the oratorical power and in the sense of historical and theological resonance.I conduct a little thought experiment by picking up a couple of the biblical turns of phrase, rewording them in order to eliminate the biblical echoes, and then asking what the difference would be in feel and meaning. It is, I think, an instructive illustration of how style makes a significant difference in what is said. And, as such, it prepares the way for the reader to follow what I do in discussing style in the various novels from Melville onward.Why, for example, does the Gettysburg Address begin with “Four score and seven years ago”? Is that somehow different from “Eighty-seven years ago”? The phrase, incidentally, is not an actual quotation from the King James Version but is patterned on the frequent occurrence of “two score” in the 1611 translation.I invite readers to see that this biblicizing initial phrase of the Address creates a perspective for what is said that could not come into place without the Bible.Much of what I regard as the book’s larger context, at least concerning the study of literature and of American literature in particular, is spelled out in above.To that I would add the following thoughts: Literature, unlike technology, very rarely discards its earlier significant phases. We no longer think about the abacus, except as a curiosity, when we have computers. On the other hand, we are still living with Homer and Virgil and Shakespeare even though we are many centuries removed from their worlds.For me, the presence of the Bible in American culture, in the very texture of the language written by some of our greatest writers, is something we still need to come to terms with.Outside of evangelical circles, biblical illiteracy in contemporary America is notorious. And we certainly are no longer the kind of Bible-suffused culture we once were. Yet, the Bible remains with us. And even in the twenty-first century, there are some American writers who still quarry from it the building-blocks of their prose.Edmund Wilson once remarked that this is a book we have been living with all our lives and that we can never quite accommodate to our lives. It is that dynamic and ambiguity in American culture that Pen of Iron seeks to address.