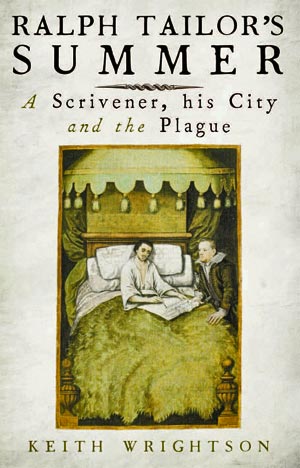

Your browsing reader might be attracted by the striking cover of the book, which shows a dying man making his will, while a friend leans forward at his bedside, looking at him intently. It is the frontispiece from the Braithwait Bible, a beautifully customized Geneva Bible, made around 1607 in memory of Thomas Braythwait, which is now in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art.

Having got that far, I hope the browser would pick up the book and open it first at the Prologue, and then perhaps turn to the final page. (That is what I do myself in such situations: first paragraph and then last paragraph.)

On page 1, the reader would immediately encounter a reproduction of the elegant and elaborate signature of Ralph Tailor, which is described in my first paragraph.

It was my own encounter with that signature that began this book. The following pages describe how I came upon it, at the bottom of a deposition made before the probate court of the Bishop of Durham in 1637. It stopped me in my tracks because it was so unusual.

Most people in this period signed depositions with a rather labored hand, or simply made a mark because they could not write. This was the work of a professional penman.As a result, I read the deposition, and found in it an account of how on 8 August 1636, Ralph Tailor, accompanied by two witnesses, climbed up on to the city wall of Newcastle in order to get close to the attic window of a house located by the wall.

From that window a man called Thomas Holmes dictated the terms of his will, which Ralph took down. Thomas Holmes was dictating his wishes from the attic window because he was isolated there. He was dying of the plague.

That deposition first alerted me to the fact that the testamentary records of 1636-7 contained a wealth of vivid evidence about the terrible plague outbreak in Newcastle in 1636. It also introduced me to Ralph Tailor. As I read on I encountered him repeatedly in the records, and both the potential of the material and the presence of such a central character caught my imagination. My Prologue describes all this. It is intended to explain how a historical research project of this kind gets started. If the reader finds that intriguing, then he or she may well find the book rewarding.The final paragraph of the book, on p. 161, is a reflection on how most past events (including the plague of 1636) fade and are forgotten—but also on how they can be recovered.

The records are still there. They tell stories. They name names. They contain voices that deserve to be listened to. My book is an effort to hear and interpret them. All historical events leave echoes, but they do not resonate with equal force or share the same capacity to persist.

Phillip Abrams defined an “event” as, “a happening to which cultural significance has successfully been assigned.” Accordingly, most historical writing is focused upon canonical events that have become regarded, in particular societies or cultures, as historically significant.

William H. Sewell goes further to suggest that, “historical events should be understood as happenings that transform structures.” Such meaningful and transformative events echo loudly from the start. They are the great events that become accepted as the chronological landmarks and reference points of history as we conventionally understand it. Most actual events, however, are assigned no such larger societal meaning and lack such transformative power.

They may have been of no less importance to the people who lived them, but they fade, fall into the shadows, become devalued and irrelevant in the grander scheme of things. The Newcastle plague of 1636 was such an event. Surprisingly soon it was forgotten in the official history of the city it devastated.I am interested in such lesser, gradually forgotten, events; and the historically insignificant people who lived them. I find both much more engaging than the conventional historical agenda. It is more of a challenge to recover the texture and meaning of these moments and these lives.

This does not mean that I am unaware of the significance of “great historical events.” They are an essential starting point in anyone’s historical education. But they are a very limiting end point. I want people to have the opportunity to move on and consider other histories. They are no less interesting and significant.

I have always been more fascinated with the more obscure narratives of what was going on between and around the great events. I think the real meaning lies there, in the sense that they can reveal the complexities and ambiguities of former states of being.

People lived their own lives in ways that intersected only partially with the grand narratives of historical change. I am drawn to the more ordinary agents of history. I am intrigued by their very different time lines. I want to tell their stories. I think that helps us, in Peter Laslett’s phrase, to “understand ourselves in time.” This book is another small contribution to that project.