Although The Fall of the Wild is text-driven, it contains a number of photographs, some of them quite famous in the visual history of wildlife conservation. Chapter three (“The Call of the Quasi-Wild”) is focused on zoos and their relationship to the wild. It opens with a discussion of the case of the American bison or buffalo, a species that was pushed to the edge of the cliff by hunters in the 19th century.

The photograph on page 40 features a staggeringly huge mound of bison skulls stacked so high they dwarf the human figures in the scene, one of whom is standing on top of the pile proudly brandishing a skull, presumably for the photographer. The skulls were on their way to being ground up for fertilizer, but the moment captured in the picture is indelible. Tens of millions of animals would be slaughtered on the plains, a pace that accelerated when a commercial market in bison leather took hold in the last third of the 19th century.

Although many of the cases discussed in the book end with a species lost forever, the bison is an example of a species that was pulled out of the fire by the timely efforts of conservationists, including a pioneering breeding and reintroduction program at the Bronx Zoo. In fact, another photograph in the chapter is of a bison being prepared to ship to a preserve in Oklahoma, a picture that signals not just a shift in the animal’s fate but a remarkable transformation in conservation ethics over only a few decades.

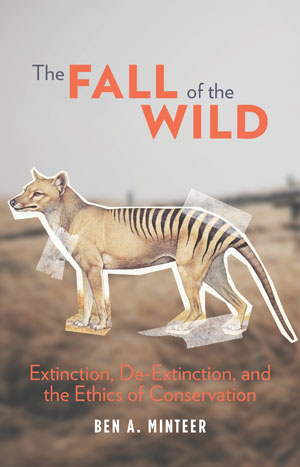

Another powerful image appears later in the book in the chapter “Promethean Dreams.” In the left side of the frame is a dead Tasmanian tiger (aka thylacine), a large, carnivorous marsupial with a distinctive striped back. The animal is strung up by its hind quarters, facing the hunter who took the fatal shot, a man identified only as “Mr. Weaver.”

The thylacine was persecuted by sheep farmers and bush hunters in Australia’s rugged island state in the 19th century, even though the failure of the Tasmanian sheep industry owed more to human incompetence than to these allegedly “bloodthirsty” marsupials. Unlike the bison, the thylacine’s story doesn’t have a happy ending. “Benjy,” the last of the species, died in a Tasmanian zoo in 1936.

The thylacine has emerged as one of the candidate species for “de-extinction,” an effort to use high-tech genetic methods to try to bring back lost species using remnant DNA from museum specimens. In The Fall of the Wild I argue strongly against this idea, suggesting that in celebrating and applying human technological control over nature, it represents not a moral reversal toward species we wantonly destroyed in the past, but rather a failure to learn the lessons that drove species like the thylacine to extinction in the first place.

I hope The Fall of the Wild makes us think deeply about the moral consequences of our more aggressive efforts to save and restore biodiversity, especially during what appears to be a time of great upheaval in conservation. The caution and restraint characterizing an older preservationist approach to wildlife and wild places have explicitly been called into question by “new” conservationists more enamored of technology and development – and less concerned about safeguarding a wild nature beyond our grasp. But I also want the book to reach a wider audience, especially readers who may be unfamiliar with some of the events and trends it discusses.

Many people care about the future of wild things but simply haven’t had the time or the occasion to stop and think about some of the trade-offs and moral questions raised by our increasingly manipulative and interventionist attempts to conserve a biologically diverse future. The traditional threats to wild species – i.e., bulldozers and bullets, pollution and (over-)population – rightly attract the lion’s share of attention in our conservation efforts.

But as the book demonstrates, our impressive conservation techniques and ambitions can also raise troubling concerns about our environmental ethics, especially if we forget that we are merely one species among many, albeit a very clever and uniquely powerful one.So I hope The Fall of the Wild is successful in carrying this message forward, and that it might spark a larger discussion about what we think we are doing, and, more importantly, what we should be doing, in our dogged fight against extinction.