I would like readers to look closely at UNESCO’s high-profile Nubian Monuments Campaign, coming as it did right after the disastrous Suez crisis. In the twilight of empire, during just over a week in late 1956, Britain and France followed Israel in invading Egypt. The three nations colluded to wrest the Suez Canal from Egyptian control and remove Gamal Abdel Nasser from power. With the major powers again poised on the brink of war and set against the backdrop of the Cold War, Arab nationalism, and Arab–Israeli tensions, UNESCO attempted its most monumental project of global cooperation. The Rescue of the Nubian Monuments and Sites (1959-1980) fully realized UNESCO’s central message of world citizenship from its very bedrock. It paired the ideals of the liberal imperialist past and its cultural particularism embodied in ancient Egypt with UNESCO’s own inherently Western promise of a new scientific, technocratic, postnational future.

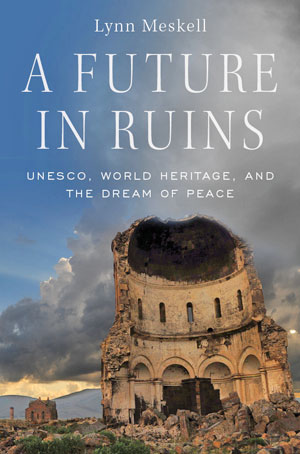

So much has been written about UNESCO’s Nubian Monuments Campaign over the years: from the heroism and humanism promoted by the agency’s own vast propaganda machine to the competing narratives of national saviors, whether French or American; from Nubia as a theater for the Cold War right down to individual accounts by technocrats, bureaucrats, and archaeologists. Therefore, it would seem that there is little new to say. Yet if one recenters UNESCO’s foundational utopian promise, couples it with its technocratic counterpart, international assistance, then adds the challenge of a one-world archaeology focused on the greatest civilization of the ancient world, we might produce a new slant on a future in ruins.

As the adage goes, if UNESCO did not exist, we would have to invent it. Without its contributions in the fields of education, science, and culture it is all too easy to imagine a world in ruins.

Yet despite their initial good intentions, many international organizations like UNESCO are struggling or have failed to implement their vision to improve the lot of great swathes of the world. Whether in the fields of environment and climate change, economic development, global health, or human rights, the impediments to international organizations are most often their member states.

Perhaps it should not be surprising then that World Heritage has become so contentious. Culture and heritage are supposed to constitute a benign forum for soft power negotiations, but in fact they are intimately sutured to identity, sovereignty, territory, and history-making, with ever more fraught and fatal consequences.

As UNESCO’s highly visible flagship program, the stamp of World Heritage may prove to be both the source and the solution to that dilemma.UNESCO’s appeals to one-worldism and universality were ambitious and legible in the aftermath of a world war. For better or worse, the commitment that UNESCO embodies has been accompanied by an unshakeable confidence in the possibility of human improvement and an optimistic adherence to its mission.

Perhaps the real and unstated problem is that we imagine international organizations to be more powerful than they really are and expect them to deliver on impossible promises. Collectively we expect that they can be better than we can as individuals. The utopian dream of UNESCO, while not fatally flawed, was nonetheless tainted by the same human history and politics that it sought to overcome. Emerging from dystopia, the organization would advance its mission over the next seventy years in the best of times and the worst of times.