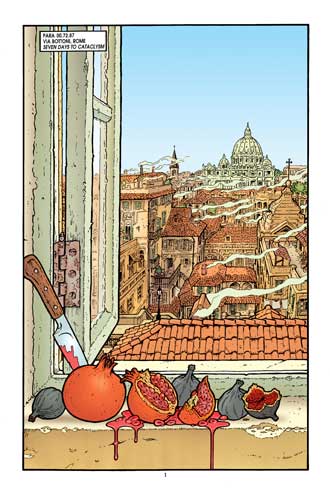

The book has more than a hundred full-color illustrations, many of them full page, each directing attention to the forms of material objects with which comics creators fill their frames and against which they situate their characters. If we assume that a picture is worth a thousand words, this is an author’s dream—another 100,000 words to play around with as I make my argument.When I flip the pages, my eyes most often end up on p. 73 which features a page from Brian Talbot’s Heart of the Empire: a vivid splash of line and color. Talbot, who knows his art history, draws on several genres of traditional paintings, including both a still life in the foreground and a richly detailed depiction of urban architecture and cityscapes in the background. I love the lush image of the figs and pomegranates both dripping their juices down the windowsill.

Traditional still life paintings often were not entirely still, showing bugs crawling among the flowers, animals romping around the edges, or flowers shedding their petals. Talbot has a particular love for the Edwardian and Victorian era and inserts material objects drawn from references he finds on the web or in his own backyard. Such details represent a form of conspicuous display of his productive capacities, since these images may take days, and he gets paid no more as a commercial artist than if he knocked off a much simpler image.My other favorite is p. 247, which features an image from C. Tyler’s A Good and Decent Man, which she republished as the omnibus Soldier’s Heart. Here, she provides a detailed depiction of her father’s workroom, including many objects that play central roles across the narrative as a whole and others equally evocative that never surface again in the story. She wants this drawing to capture her father, an embittered World War II vet, in the place he feels most at home and to give that place as much concreteness as she can.

She does something similar with her mother, who is a far less active presence in the book, but whose presence is felt through decorations, especially handicrafts associated with the major American holidays, such as Christmas, Easter, Halloween, and the Fourth of July. Here, the mother is the person who keeps the family going year after year even as Carol, the daughter, is the one who preserves family history.As the chapter discusses, Soldier’s Heart is structured around a family project as Carol builds a scrapbook to help her father process his repressed wartime memories, while the graphic novel itself functions as a kind of scrapbook as Carol explores how her whole family experienced “collateral damage.” I trace the history of scrapbooking practices and how they have influenced many graphic women as they turn to graphic novels to share aspects of their own lives.In terms of “comics,” I want to expand the conversation around graphic novels, broadening the range of works that comics scholars discuss, but also changing the ways we write about them. The early emphasis on comics as “sequential arts” has understandably focused a lot of attention on framing, juxtaposition, and decoupage—on how we break down a sequence of images across the page in order to shape the reader’s perceptions.

This is perhaps what distinguishes comics from other kinds of graphic storytelling.I also want to focus attention on mise-en-scène, on the expressive anatomy and material details that are juxtaposed within the same panel, and the invitation comics offer us to scan and flip as we explore their images in search of meaning. Shifting the focus to mise-en-scène offers parallels with a range of other minor arts—such as scrapbooking or cabinets of curiosity or collage—which depend on juxtapositions between elements of material culture.In terms of “stuff,” I want to encourage reflection on how we narrate our relationships with the things we choose to surround ourselves with. Comics are only one contemporary mode of expression which helps us make sense of our stuff. We might point to the broad array of television programs—such as Tidying Up with Maria Kondo, Hoarders, or Antiques Roadshow—or YouTube’s unboxing videos which address our societal fascination with everyday things.And I draw analogy to a number of artists and literary figures—Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, Henry Darger’s scavenger art, Jonathan Franzen’s list-making in The Corrections, and Kare Walker’s reclaiming of racist iconography. All of this suggests that the social and cultural questions surrounding collecting, accumulation, inheritance, possession, and culling have implications far beyond the specific comics I discuss here.