Valerie Steele is director and chief curator of The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, where she has organized more than 25 exhibitions since 1997, including The Corset: Fashioning the Body, London Fashion, Gothic: Dark Glamour; A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk, Pink: The History of a Punk, Pretty, Powerful Color and Paris, Capital of Fashion, Dress, Dreams, and Desire: Fashion and Psychoanalysis. She is also the author or editor of more than 30 books, including Paris Fashion, Women of Fashion, Fetish: Fashion, Sex and Power, The Corset, The Berg Companion to Fashion, and. Fashion Designers A-Z: The Collection of The Museum at FIT. Her books have been translated into Chinese, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. In addition, she is founder and editor in chief of Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture, the first scholarly journal in Fashion Studies. Steele combines serious scholarship (and a Yale Ph.D.) with the rare ability to communicate with general audiences. As author, curator, editor, and public intellectual, Valerie Steele has been instrumental in creating the modern field of fashion studies and in raising awareness of the cultural significance of fashion. She has appeared on many television programs, including The Oprah Winfrey Show and Undressed: The Story of Fashion. Described in The Washington Post as one of “fashion’s brainiest women” and by Suzy Menkes as “The Freud of Fashion,” she was listed as one of “The People Shaping the Global Fashion Industry” in the Business of Fashion 500: (2014 to the present).

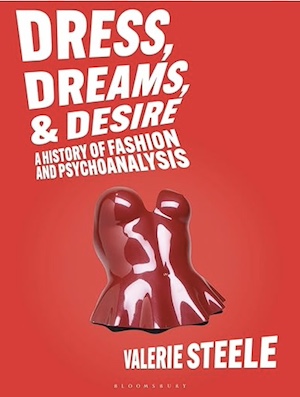

Dress, Dreams, and Desire is a book on the cultural history of fashion and psychoanalysis. It traces how psychoanalytic ideas have influenced fashion and how we interpret fashion.

On the one hand, you have Freud's writings, where he barely mentions clothing or fashion at all. Just tiny little intriguing slivers, like the libido for looking, or the attraction of concealment. And yet, when you look at his personal letters to his fiancée, he talks a lot about the anxieties and desires he has when he is shopping for clothes. So, there's this tension that psychoanalysts are not supposed to be very interested in fashion, and yet we find that they are often interested in fashion. Jacques Lacan, for example, only mentions fashion occasionally, but was obviously quite obsessed with dressing up. And he comes up with ideas, like the mirror stage, which can tell us a lot about the development of a person’s self-image, and how that can be expressed in clothing.

I trace how psychoanalysis influenced society. For example, in the 1920s, when Freud began to be widely translated, a lot of people started identifying psychoanalysis with personal and sexual freedom, particularly for people who had been rather repressed, like young unmarried women or members of sexual minorities. And then later in the 1950s, especially in the United States, psychoanalysis becomes very conservative, homophobic, misogynistic, etc, to the point where a lot of women and gay men started thinking that Freud was the enemy.

However, some psychoanalysts took a more progressive, even radical stance, and began to argue that psychoanalysis is potentially very freeing because it can tell us a lot about people's unconscious desires and anxieties, which often have to do with their feelings about their body. For example, why do some people hate or fear women or gays? What causes group hatred? I look at key ideas in the history of psychoanalysis, from dream theory to the mirror stage to the phallic woman, and try to interpret clothes through them. In a long nutshell, that's the book.

Let's take Freudian dream theory. Pretty easy to understand. Most people know something about Freud's sex and dream theories. He talks a lot about sexual symbolism, particularly phallic symbolism, and about how dreams are often repressed expressions of sexual wishes, and sometimes also aggressive wishes. In Dress, Dreams, and Desire, I show this marvelous dress that Jeremy Scott designed for Moschino. It's a chocolate bar dress - a Hershey's chocolate bar. And I talk about how a chocolate bar is kind of a phallic symbol. It's also a symbol of oral pleasures, and, you know, chocolate melts in your mouth. So a woman wearing a dress that turns her into a chocolate bar is implying, perhaps jokingly, that women's bodies are good enough to eat. So it's very sexual.

This is quite different from Carl Jung's dream theory, where it's more about archetypes in the collective unconscious. So, for example, fashion designers often use feminine archetypes, the queen, the lover, etc, but in one case, Rick Owens makes a more esoteric choice. He does an entire collection entitled Priestesses of Longing. It is a feminine archetype, but it's an interestingly esoteric one.

There are other later psychoanalysts, such as Didier Anzieu, who developed his concept of the skin ego from Freud's idea that the ego is first and foremost a bodily ego. A baby is a little creature of sensations, who puts its hands in its mouth to understand 'oh, that's me'. The baby is being held by its mother, or some other caregiver. So it feels a sense of security if it's held closely, but not too hard, and can develop a sense of its own bodily dimensions, a sort of body and surface ego. This is not dissimilar to Lacan’s concept of the mirror stage: The mother's gaze is the child's first mirror, and if it's a relatively loving gaze, or an accepting one, then the child gets a fairly good self-image. In both cases, though, if things are not the way they should be, there can be problems, and often a sense of fragmentation.

Now, clothes can, in some ways, help provide a secondary skin that will re-narcissize you, when you're feeling fragmented or falling apart. Fashion designers often talk this way. You know, Alber Elbaz at Lanvin said he wanted his clothes to be like a hug. And, Yohji Yamamoto said, “my clothes are like armor that protect you from unwelcome eyes”. So both looking and touching can be reassuring but also threatening. Clothes, in a way, talk about how we feel vulnerable — we want to be seen, but we want to be seen in a good way. And we can also be vulnerable if people are not seeing us, if the world is indifferent to us. So clothing can make you visible to a possibly indifferent world, while also providing dark glasses that hide your vulnerabilities.

Let's take Freudian dream theory. Pretty easy to understand. Most people know something about Freud's sex and dream theories. He talks a lot about sexual symbolism, particularly phallic symbolism, and about how dreams are often repressed expressions of sexual wishes, and sometimes also aggressive wishes. In Dress, Dreams, and Desire, I show this marvelous dress that Jeremy Scott designed for Moschino. It's a chocolate bar dress - a Hershey's chocolate bar. And I talk about how a chocolate bar is kind of a phallic symbol. It's also a symbol of oral pleasures, and, you know, chocolate melts in your mouth. So a woman wearing a dress that turns her into a chocolate bar is implying, perhaps jokingly, that women's bodies are good enough to eat. So it's very sexual. This is quite different from Carl Jung's dream theory, where it's more about archetypes in the collective unconscious. So, for example, fashion designers often use feminine archetypes, the queen, the lover, etc, but in one case, Rick Owens makes a more esoteric choice. He does an entire collection entitled Priestesses of Longing. It is a feminine archetype, but it's an interestingly esoteric one.There are other later psychoanalysts, such as Didier Anzieu, who developed his concept of the skin ego from Freud's idea that the ego is first and foremost a bodily ego. A baby is a little creature of sensations, who puts its hands in its mouth to understand 'oh, that's me'. The baby is being held by its mother, or some other caregiver. So it feels a sense of security if it's held closely, but not too hard, and can develop a sense of its own bodily dimensions, a sort of body and surface ego. This is not dissimilar to Lacan’s concept of the mirror stage: The mother's gaze is the child's first mirror, and if it's a relatively loving gaze, or an accepting one, then the child gets a fairly good self-image. In both cases, though, if things are not the way they should be, there can be problems, and often a sense of fragmentation.Now, clothes can, in some ways, help provide a secondary skin that will re-narcissize you, when you're feeling fragmented or falling apart. Fashion designers often talk this way. You know, Alber Elbaz at Lanvin said he wanted his clothes to be like a hug. And, Yohji Yamamoto said, 'my clothes are like armor that protect you from unwelcome eyes'. So both looking and touching can be reassuring but also threatening. Clothes, in a way, talk about how we feel vulnerable — we want to be seen, but we want to be seen in a good way. And we can also be vulnerable if people are not seeing us, if the world is indifferent to us. So clothing can make you visible to a possibly indifferent world, while also providing dark glasses that hide your vulnerabilities.

Valerie Steele, Dress, Dreams, and Desire: A History of Fashion and Psychoanalysis, Bloomsbury, 264 pages, 7.5 x 9.7 inches, ISBN:9781350428195

%2520(1).jpeg)

.jpeg)

%2520(1).jpeg)

%2520(1).jpeg)

We don't have paywalls. We don't sell your data. Please help to keep this running!