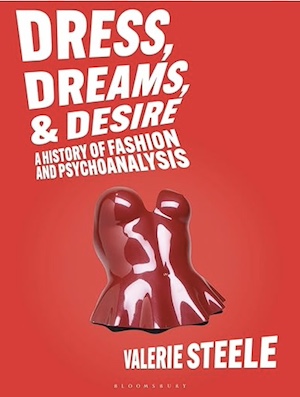

The appearance of a book is very important to me. I was playing with different images, but none of them were quite right. I wanted a fashion image, but I also wanted it to say psychoanalysis. We hired a graphic designer to do things for the museum exhibitions, and we have a very good one who works under the name Sarko (Steven Sarkowski). He came up with this wild graphic lettering, which really sort of looked like the lettering you do for a Hitchcock film. It kind of was too radical for the publisher. They toned it down a little bit, but I liked that red graphic design, and then it suddenly occurred to me that we had a wonderful bustier by Issey Miyake, a female torso, which was bright red, and we could use that on the cover too. The bustier and the graphics really tied together the body, fashion, and psychoanalysis. I am very happy with the look of the book.

Similarly, the exhibition walks you through the history of fashion and psychoanalysis. But I also wanted to plunge people into the unconscious and the world of dreams. As soon as you enter the second, larger gallery you were confronted by a mirror, and then a few things like, fetish boots, gloves, and then after that, you wander through a labyrinth with peepholes, and you come across vignettes of the mirror stage or the death drive or a platform about ugly emotions. There was a platform with looks by McQueen, and another with Gallianos. This helps fashion people understand some of these complicated ideas.

I'm a fashion historian, not a psychoanalyst. When we had our big symposium the other day, we had a lot of psychoanalysts in the audience. I'm hoping analysts will read this book too, but for them, it will probably be, 'this is interesting, how's she bringing fashion in?' But most of my readers are fashion people. I tried to write it in a way that was accessible to people who like fashion, and who maybe don't know much about Freud, and I try to reassure them, 'you know more about Freud than you think you do'. Fashion designers frequently refer to psychoanalysis. Marc Jacobs did a Freudian slip dress; John Galliano did a whole collection for Dior, called Freud or Fetish. We all know something about fetishism or about dreams. I wanted to make it reassuring.

Early on, when I wrote a 50-page first draft, and I showed it to my husband, he said, 'This is boring. Your fans don't want to read in-depth about psychoanalysis'. I was so angry, I didn't talk to him for days, but that was useful. I had to plow through the psychoanalytic ideas before I could understand how to make them palatable. I'm not going to dump 50 pages about the Oedipus Complex. People don't want to read that.

I'm also hoping that fashion people will realize that we all interpret each other's clothes. These are just some interesting ideas that you might add to your repertoire as you're looking at a fashion show or some wild and crazy fashion look on the runway, you might think, 'oh, you know, you could interpret that as being about this'. There are some sexier styles that a lot of second-generation feminists find horrible, “that's turning women into a sexual object”. You might think, 'well, no, as Joan Riviere and Judith Butler say, maybe it's more like femininity is a kind of performance'. The art historian Linda Nochlin suggested that 'maybe the great designers create new forms of the feminine that women can play with for their own pleasure and interest'. Men usually deny that they have fashion and wear just a kind of uniform. Yet, some men, at least, especially gay men, are quite adept at playing with the masquerade of masculinity as well.

%2520(1).jpeg)

.jpeg)

%2520(1).jpeg)

%2520(1).jpeg)