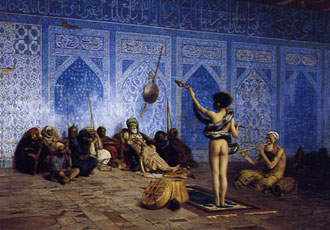

It is sometimes said that you cannot judge a book by its cover. But this should not prevent the reader of Orientalism from reading into its cover illustration. This is Jean-León Gérôme’s 1880’s The Snake Charmer. The painting highlights a naked white boy with prominent symmetrical buns facing the viewer and holding aloft the head of a large snake as the body of the reptile twists around the boy’s upper torso. To the right is an old man playing a flute to soothe the beast, while its empty basket-home shares the rug on which the boy stands.

Directly in front, staring voyeuristically at private-parts level, is an aged, green-turbaned, white-bearded “Arab” with feet outstretched and curved sword propped against his side. A mix of black and light-skinned retainers flanks his sides. This suggestive scene, counterpoint to the direct gaze on the female form in Orientalist odalisque paintings, is enshrined in an ornate palace of a bygone era with Quranic style calligraphy along the top of the back wall.

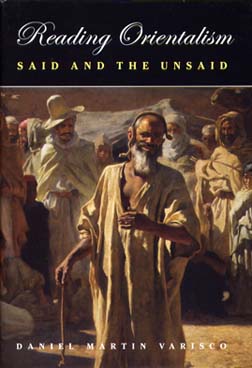

The message is one of sexual decadence and hollow faith, an iconic visual summary of Said’s thesis. The cover of Orientalism, like Said’s argument itself, only tells half of the story. The cover illustration for my book is also about a snake charmer, painted by the Orientalist painter Etienne Dinet about the same time. Dinet celebrates the nuance of outdoor light in a North African market; Gérôme focuses only on the inner darkness. While Gérôme chooses a naked boy fully exposed to an old sheikh, Dinet portrays a public charmer as an old man gazing back at the viewer.

For Gérôme the boy is engulfed by a large boa; for Dinet the small brown snakes are the harmless props of a popular prankster. The art of Dinet would be an uncomfortable fit for Said, a reminder that not all Westerners approaching the real Orient were voyeurs, dilettantes or swashbuckling rogues. Dinet combined his compassion with recognition of the humanity of those he painted, just as a number of Western scholars have done over the past two centuries. As an “Orientalist” in Said’s terms, Dinet was both sympathetic and knowledgeable of the Oriental other in the flesh. What a difference a picture can make. The major reason I want to reread Orientalism is the importance of placing what Said labeled Orientalism in a more soundly recovered historical context.

My analysis will be especially relevant for those concerned with past and present representation of Muslims and Middle Easterners in literature, the academe, and the media. The general reader interested in how Western authors and scholars have represented the Orient and Islam will find this a useful summary of the main points discussed over the past three decades in the course of an animated and crucial debate. Said’s text is not about to disappear from bookstores and university reading lists. But its polemical force cannot compensate for three decades of criticism, even from those who agree with Said’s overall aim of highlighting past bias.

In my book, I seek to redirect the unending debate over Orientalism to the merits and demerits of its arguments and away from personal attacks upon or uncritical veneration of its author. It is important to re-orient the debate over Orientalism in order to facilitate cross-cultural understanding beyond the binary of East vs. West.

But why write textual criticism as satire? The Roman poet Horace reminds us that although the satirist laughs, he tells the truth. Voltaire and Swift are still read today, not simply because they are amusing, but because they speak the kind of truth that outlasts the passion of polemics. I am not pulling for prime space on a future library shelf alongside the important corpus of Edward Said, but I do offer the reader of Orientalism a companion guide with pun in cheek.