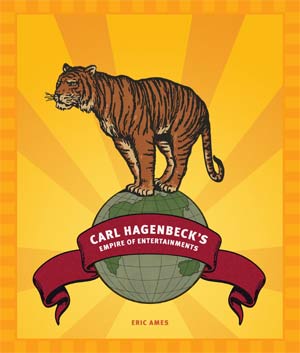

This book tells the story of one of the greatest showmen in the history of zoos and circuses. Carl Hagenbeck (1844-1913) may not be well-known today, but his name was once as evocative and celebrated as that of P. T. Barnum and Buffalo Bill. In the late nineteenth century, when zoos were being built at a rate of almost one per year, the Hamburg-based entrepreneur was hailed as the world’s leading supplier of wild animals. The infrastructure that enabled him to capture and trade wild animals also became a platform for Hagenbeck’s venture into public entertainments, beginning with his so-called “anthropological-zoological exhibition.” It was a high-sounding name for the practice of grouping together “exotic” humans and animals in the same space of display—a practice that soon became a regular attraction of world’s fairs.Between 1874 and 1913, Carl Hagenbeck sponsored and exhibited as many as one hundred different troupes of “foreign peoples,” becoming the most important ethnographic showman of the period. And that was not all. In 1907, Hagenbeck unveiled his revolutionary Tierpark (or “animal park”) on the outskirts of Hamburg. Its unusual design fundamentally changed the way that live animals were displayed and observed by staging them in natural settings and so-called open enclosures (cage-less displays). Both of these practices would later be imitated by zoos across the board.At the time, however, Hagenbeck’s park was not a zoological garden. It was an early theme park, combining live animal panoramas, ethnographic performances, native villages, moving pictures, mechanical rides, and merchandise—all themed around the exotic. Drawing on all this material, I show that Hagenbeck helped shape the preference of mass spectators for immersing themselves in themed environments, for physically plunging themselves into fantasy worlds of wild adventure.More than just a descriptive account, Carl Hagenbeck’s Empire of Entertainments re-envisions the way in which themed environments have been made and experienced in history. Specifically, it fleshes out the dominant practice in the late nineteenth century, which was based on choreographing the material objects and living bodies (humans and animals) on display, while immersing spectators in the simulated environment. This part of the argument is made especially vivid by the book’s design: It is a large-format volume with more than eighty illustrations—maps, drawings, paintings, postcards, photographs, film images, and advertising posters—fourteen in color.