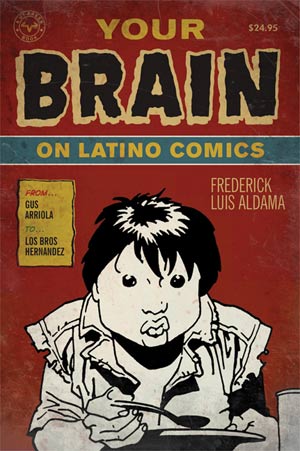

Your Brain on Latino Comics provides readers with an understanding of how comic books in general work to move us and to engage our critical faculties and imagination. It also opens our eyes to how authors of Latino comic books (and comic strips by the likes of Gus Arriola and Lalo Alcaraz) choose to tell stories in any number of genres and styles: from the superheroic to the domestic, to the bitingly political and satirical.We see in such choices also how author/artists of Latino comics overturn preconceptions of Latinos—not only as represented in mainstream DC and Marvel comics since the first appearance of Firebird (Marvel) and El Dorado (DC) in the late 1970s, but also in the sense that Latinos in comics are much more than Spanglish-speaking, taco-eating, pre-Columbian-ancestrally connected figures. Just as their creators, they represent the full and rich range of human experience and personality types.Moreover, such author/artists defy such pre-packagings of Latinos precisely because their ambition is to tell and draw the best story possible—stories that they want to be judged along with the best. As the interviews attest, making a good comic book about Latinos is less about blood quantum than about responsibility to creating an engaging story, in form and content.To refer to one of the interviews included in the book, when people see Frank Espinosa’s last name, they jump to the conclusion that all he knows is Latino culture. But he insists that he also knows about Ancient Greek literature, Japanese art, and all the rest. All the author/artists here seek to shed the straightjacket of identity politics that constrain their imagination.All while recounting the history of how Latinos have been represented in mainstream comics, and creatively imagined by author/artists working today, Your Brain on Latino Comics also tells something about how author/artists of Latino comics infer inner states of mind, emotion and thought, from outward gesture and expression.From the very get-go when I conceived of the book, I felt a strong impulse to join critical analysis together with a polyphony of actual author/artists of Latino comics speaking about the craft. As a result, I was able to interview author/artists such as Laura Molina, Rafael Navarro, Roberta Gregory, Frank Espinosa, and Los Bros Hernandez, to name a few.Your Brain on Latino Comics is the realization of my ambition: to offer a solid understanding of how Latino comic books work, as well as to give readers a firm grasp of the aspirations and goals that these author/artists set for themselves in the creating of comic books. This abundance of voices and takes on the craft should give readers a clear picture of the Latino comic book in the United States today.