Description of the personal efforts of distinguished past foes of corruption is a leitmotiv set up in pages 21-25 and repeated in the opening sections of each subsequent chapter. The first pages of chapter 1 frame the dilemma of don Antonio de Ulloa (1716-1795), an enlightened governor of the mining center of Huancavelica, a strategic source of mercury in the viceroyalty of Peru in 1757. Armed with a reformist training and honest intentions, Ulloa detected day after day what he termed his “purgatory” in dealing with appalling maladministration and dangerous neglect of the mines.

Counting with the support of the royal council in Madrid, Ulloa was very aware of the urgency of reforming the management of mercury supply essential for the amalgamation process in silver production. Silver was the main source of American wealth fueling the Spanish empire and its involvement in European wars. However, in Huancavelica Ulloa found that groups of miners, merchants, and even priests conspired to drain as much private benefit out of the royal mines and the indigenous population.

These corrupt networks had a long reach all the way to the viceregal court in Lima.Ulloa’s reformist measures were bitterly opposed in Huancavelica. He even got in deep legal trouble in Lima accused of the same crimes he was trying to stamp out. One viceroy, the highest authority in Peru at the time, became Ulloa’s most bitter enemy. After several years of troubles and persecution, Ulloa was able to leave Peru in defeat despite his valiant fight.

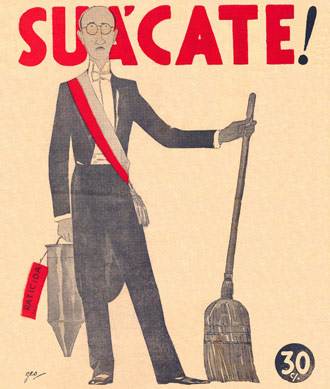

The letters, reports, and analytical essays Ulloa wrote, to inform Madrid how corruption operated in Peru, are true historical windows for studying connections between past and more recent manifestations of costly graft. Ulloa’s Noticias secretas de América, coauthored in part with his fellow naval officer Jorge Juan and published only in 1826, can be considered one of the first anticorruption treatises in Spanish America.Other valiant personal and mostly frustrated efforts at reform included the actions and writings of Domingo Elias (1805-1867), Francisco García Calderón Landa (1834-1905), Manuel González Prada (1844-1918), Jorge Basadre (1903-1980), Héctor Vargas Haya (b. 1928), and Mario Vargas Llosa (b. 1936).

Their stories can be followed in the context of the corrupt administrations they had to deal with. Through their detective, journalistic, and activist work, and together with a host of new anticorruption reformists arising just after the fall of Fujimori, these admirable individuals have contributed to hopes that one day the damaging excesses of corruption will be controlled in Peru. To document and write the history of corruption in Latin America and other developing parts of the world, there is still a lot of work ahead.

I hope for my book to contribute to the historical treatment of the persistent phenomenon of uncurbed corruption, a burden too heavy to carry by impoverished citizens.

The historical visualization of the problem and its negative consequences can help present endeavors to fight and control corruption. A thorough anticorruption reform must include constitutional checks against it and an end to the customary tradition of impunity. The stiff punishment applied by Peruvian courts to those who led the most recent frenzy of corruption in the 1990s is an auspicious start that could be, however, easily reverted.Anyone who travels or engages in business in those parts of the world were corruption reaches high levels should be aware of the long history, enormous costs, and past efforts at curbing graft. Most importantly, by learning from past anticorruption efforts, the citizens of countries flagellated by corruption will hopefully rise to the task of punishing and not condoning the corruption of “strong” governments that deceitfully appeal to popular support.

The danger of uncontrolled corruption also exists in developed countries were corruption has been historically curbed. Corruption and its concomitant abuse of power could raise its ugly head at any moment if the walls that circumscribe it are not periodically reinforced.