Histories of the long, prosperous liberal consensus in the middle of the twentieth century looked back to the specific experience of the industrial North. The people and institutions of the New Deal order were urban, modern, radical, immigrant, internationalist. But rural Southerners made up influential segments of labor, management, and consumers for the economy that displaced Detroit after World War II. They drew on quite different experiences to build Fordism’s successor in the rising Sun Belt.In Wal-Mart’s home territory, the company was largely staffed with people who left farms for service jobs without ever passing through factories.

They brought different ideologies with them—not the dynamo but the dime store, not the union but the Pentecostal church, not the heroic myths of industry but the parables of Christian service. When the American economy grew to its post-war dominance, then, it carried these traditions to an international stage. The economic vision we call neoliberalism, Thatcherism, Reaganomics, or free-market fundamentalism could also claim the title of Wal-Martism.For the New Deal’s redistributive policies ironically pulled capital out of the industrial Northeast and down Route 66.

Then as now, the robust defenders of capitalism saw no contradiction in building private enterprise on public subsidy. So long as the state relinquished any right to oversight, the Sun Belt’s champions of free enterprise would deign to cash the checks—as would the burgeoning faith-based sector. With its infrastructure in part underwritten by the public, Christian free enterprise grew up through the new service industries of the South and West. Just as the shock of factory discipline had reverberated through the culture of an earlier century, the new experience of mass service employment demanded a new ethos of service to dignify it.

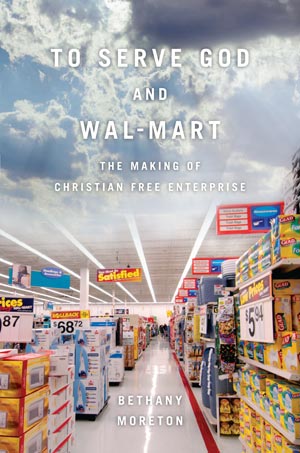

On the job, at church, and in many evangelical homes, this elevation of service work—reproductive labor—evolved into the Biblically-inflected management philosophy of “servant leadership.”Caught up in a regional revival, the white working mothers who staffed the stores changed the nature of their work as surely as the Flint sit-down strikers had a generation earlier. But the labor victories at the early Wal-Mart addressed different priorities, and so didn’t register within the terms set by the old industrial narrative. To Serve God and Wal-Mart uncovers these hidden struggles, without whitewashing the fundamental moral violence of a Wal-Mart economy.