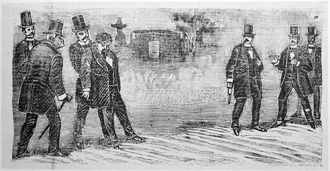

Mexico emerged as a modern nation in the 1860s, after half a century of civil war, foreign invasion and political instability. In a new nation divided by ethnicity, class, religion and differing views of sovereignty, even the basic rules of political culture had to be sorted out. The right to speak in the name of public opinion was not automatically granted to a selected few, but was the object of constant debate. Who could speak or write in the name of Mexican society? What gave him, or her, the authority to do so? Historians have explored this struggle in terms of ideology (liberals against conservatives, republicans against monarchists) or class (the elite and the subaltern). But honor was the category generally accepted, even across gender divides, as the foundation for the interactions among Mexican citizens, and between Mexico and other nations.In Mexico, honor mutated drastically with the end of colonial domination. Whereas in the past honor was the visible marker of status and formalized the interactions between people divided by class, color and gender, after independence all Mexican citizens, regardless of color or ethnicity, had a rightful claim to honor. Honor was the point of reference to build a modern masculinity, it gave men the right to use reason publicly. This book looks at the first century of Mexican history as a simultaneous struggle to protect honor and empower public opinion.Multiple press codes set out to guarantee, and at the same time limit, freedom of speech. Honor and freedom of speech were intertwined because republican honor meant the intimate connection between one's reputation, its external dimension, and the inner domain of conscience and self-esteem. When a citizen spoke, it was tacitly accepted that he or she was speaking his or her mind. Without sincerity there could be no public debate. As a result, the limits to freedom of speech most commonly legislated were those intended to protect the honor of interlocutors.Journalists, principal actors in my book, were sent to jail for libel more often than for inciting rebellion. Mexican newspapers, particularly since the 1860s, provided the field in which personal honor was tested and measured. Following romantic notions of sincerity and heroism, journalists challenged each others' reputations and defied men of power. I examine other terrains as well: Mexico City streets, where parliamentarians, students and the plebs protested in 1884 against the negotiation of the debt with British bondholders; the personal disputes in bars, commerce, and tenement houses that drove people to sue each other for defamation or insults; the secretive, yet very public, field of honor, where elite men used the duel to solve their least treatable conflicts.