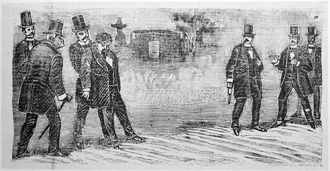

There are two episodes, in chapters two and seven, that I hope will reward the patience of the reader. Two duels, one in 1880 and the other in 1894, mark the apogee and the decline of the formalized use of violence among Mexican elites. In the first one, opposed views about the incoming presidential election lead to an increasingly acerbic polemic between two newspapers, La Patria and La Libertad. The editor of the former, Ireneo Paz, challenged a writer of the latter, Santiago Sierra, on the mistaken assumption that he had authored a particularly virulent column in La Libertad. From the balconies of each newsroom, as both had offices on the same street in Mexico City, they dared each other to back up their words with actions, and their seconds arranged a meeting in a forest outside Mexico City.Paz had participated in the war against the French and the conservatives as a supporter of the caudillo Porfirio Díaz, and was a seasoned journalist and printer; Sierra was a young and promising poet whose family came from Yucatán and had close connections with Díaz. Both were very similar in their romantic and bohemian attitudes about freedom and sincerity. In the duel, both missed in the first round, but their seconds, including the journalist who had really written the offending words, forced them to be serious. Sierra died and Paz could only apologize to the victim’s brother, Justo, as he arrived late to the field of honor. Nobody was prosecuted, Paz continued his career as a printer although he never regained the friendship of Díaz, while Justo Sierra decided to quit journalism and devote himself to education and literature, eventually becoming one of the most important historians and ministers of education in the Mexico’s history.The second duel reflects the changes that took place in public culture around the idea of honor. As he was entering the home of the Barajases, a socialite couple with deep connections in government and the elite, colonel Francisco Romero heard Stamp Administrator José Verástegui make a disparaging remark about him to Ms. Barajas. After a complicated series of negotiations, a duel was arranged and Romero, who was a very good marksman, killed Verástegui, whose ample body offered an easy target for the dueling pistol.In contrast with other cases, and perhaps because of Verástegui’s position in the administration, this time those involved were prosecuted. As Romero and the seconds were members of Congress, the case was discussed on the floor of the Chamber of Deputies and they were stripped of their parliamentary immunity. The trial was the occasion for a debate in the courtroom and the press. In addition to the revelation that the two duelists were competing for the affection of Ms. Barajas, whose husband had to testify, the scandal elicited public criticism to the very idea of honor as a value that was worth a man’s life. Romero was sentenced to prison, although quickly pardoned by Díaz. But the case clearly signaled the shift from a romantic notion of personal integrity, in which a clean conscience and a good name was worth life itself, to a positivist view of honor as a good that the state could protect, and therefore should not be placed above the authority of Díaz and the law.It is difficult, even risky, to predict how a history book will be used by its readers. I have always been wary of history books that present information about great men intended to serve as example for contemporary decision-makers. It is much more fun—although it probably sells fewer copies—to try to understand how the very category of “great man” came to be.The emergence and hegemony of public men in Mexico has its own history, and I hope The Tyranny of Opinion provides a useful path for a critical reading of it. More importantly, perhaps, the book shows the connections between public life and other, less prestigious but more intimate terrains of culture and social relations. One, alluded by the title, is the anxiety that the protection of honor imposed on men and women of all classes: it was not possible to avoid responding to any direct or indirect statement that undermined one’s reputation, whether it happened in the newspaper, the bar, the theater, the sidewalks or the market. It was a constant vigilance that in some cases resulted in the need to use violence or seek the protection of the police, and was always economically and emotionally costly.I tried to rethink politics as an object of study. The political history of Mexico and other Latin countries has too often been told as one of the naked exercise of power by the elites over the subaltern. In these views, class exploitation, racial discrimination, foreign pressures are some of the forces that ultimately explain the permanence of inequality and authoritarianism. I hope to contribute to a growing body of Latin American historiography that, against these views, contends that Latin America was, from the beginning of independent life, a territory of struggle for democracy, full citizenship and freedom of speech. It is the permanence and modalities of that struggle that needs to be explained, rather than our superficial contemporary views about the region as an instance of failed modernity.I argue, in sum, that honor, even violence, played a positive role in building an autonomous space for political debate for Mexican citizens in the late nineteenth century. But it came at a very high cost: the exclusion of women from public life and, indirectly, the justification of violence against them when their autonomous words or actions were thought to undermine the authority of men. Mexican women were able to vote only in 1953, and sexual violence has plagued everyday life up to our days. Both facts are related in that they are based on the premise that the voice of women should not be too loud in public settings, be it the press, political campaigns, or courtrooms.