The completion in 1884 of the Washington Monument—the great obelisk in the center of the Mall—is the pivotal moment in the book’s larger narrative. While the project began in the early nineteenth century, it wasn’t until a brilliant West Point officer named Thomas Lincoln Casey, from the Army Corps of Engineers, took hold of it in the late 1870s that the monument would finally be finished.

Casey became obsessed with the ancient purity of the obelisk form and the technical challenge of how to inflate the form into a modern electrified skyscraper. Initially dismissing the whole project as the “football of quacks,” Casey soon imposed his own personal vision on it, despite the united opposition of Congress and the art world to the obelisk scheme. He transformed the early-nineteenth century idea of a Revolutionary pantheon into a plain, crystalline shaft equipped with an elevator and observation windows at the top— a technological marvel in rigorously abstract form. How he managed this feat is a tale of engineering and bureaucratic wizardry.

For a short while the Washington Monument became the tallest structure in the world. The great shaft introduced a new spatial experience into the Mall landscape and signaled the beginning of the end of the old scheme of public grounds.

In many respects the story is typical of the aesthetic and political controversies that have plagued the memorial landscape from the founding of the nation. Americans have long had a love-hate relationship with the public monument. In the earliest debates Congress had on the subject of a memorial to George Washington, many argued that Washington needed no monument and that monuments were “good for nothing” in a democratic society.

The question of the appropriate form was at once a political question, as partisan as any legislative issue then or now.But due to the scale of the project, and the rigor of Casey’s approach, the Washington Monument became a unique achievement, a game-changing accomplishment. In its final form it had absolutely nothing to do with the wooded grounds and gardens that surrounded it and was a strange departure from the heroic statues that populated the city’s streets and parks.

Visitors who took the elevator to the top found themselves in a new abstract spatial realm, so far removed from the ground that the ordinary benchmarks of human existence no longer seemed to apply. On the ground many continued to wrestle with the monument’s mystifying blankness; they imagined that the monument would one day be “finished” with appropriate inscriptions or narrative scenes. But the real completion of the monument would come when the landscape around it was cleared and transformed, creating a new, more abstract space that would remold the nation’s center in the monument’s image. Without Casey’s magnificent obelisk, the nation’s monumental core might never have emerged.At the end of the book I discuss the paradox of the public monument: meant to be permanent and “timeless,” monuments typically slide into obsolescence.

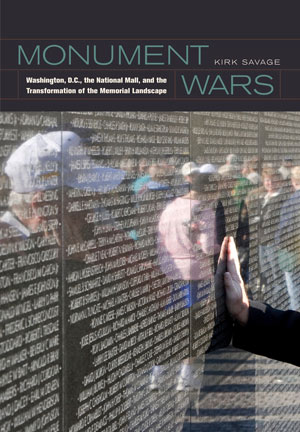

Even as brilliant a monument as Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial has lost some of its original charge as the veterans of that era grow old and the events retreat into ever more distant memory. For this reason the sponsors are now planning a huge underground visitors’ center near Lin’s wall, which will supplement her memorial with museum displays about the war and pictures of the men whose names appear on the wall. But this solution simply raises new questions. Does every war memorial deserve an accompanying museum? And who deserves a monument in the first place? If the twentieth century witnessed a shift from the great hero to the ordinary soldier and even to history’s victims, then which victims merit a name on a wall or a picture in a museum?Meanwhile the great space of the Mall has already changed radically since its birth in the mid-twentieth century.

The Civil War theme of its original design has been overshadowed by a series of major monuments to America’s wars in Europe and Asia. Since the attacks of September 11, the space itself has been carved up by security walls and by the immense new barrier of the World War II Memorial. Yet despite all these changes the monuments that get built continue to be the products of special interest groups that can successfully navigate a byzantine legislative and regulatory process. Change occurs, but in a haphazard, ad hoc way.

To expand the possibilities for democratic debate and representation, the closing pages of Monument Wars propose a moratorium on permanent public monuments in the capital, and a period of experimentation in which many groups and designers would be empowered to erect temporary memorials and installations.

While it is doubtful that this simple proposal will find much support in the current political climate, I am gratified that the book is being read and discussed within the planning bodies that do have responsibility for stewarding the Mall and its monuments. If Monument Wars can make even a modest contribution to a more open and informed national conversation about the landscape of public memory, then it will have done its job.