The first time I visited Carnegie embryo collection, I had just finished reading Bobbie Ann Mason’s 1993 novel, Feather Crowns. Mason tells the story of a hardworking farm wife named Christianna Wheeler, who gave birth to quintuplets in rural Kentucky in 1900. Strangers descended on the homestead to gawk at the tiny babies, who succumbed one by one to fever, insufficient milk, opium-laced soothing syrup, and “being handled too much.”

The undertaker convinced the grieving Wheelers to have the bodies embalmed and sealed in a glass case. Several months later the Wheelers, broke and desperate for cash, agreed to accompany the corpses on a carnival tour. They traveled through the South, enduring the stares of coldhearted curiosity seekers who paid a dime to witness their misfortune. One night, the Wheelers stole away and boarded a train to Washington, where they donated the quints’ bodies to the Institute of Man, which kept, in Mason’s words, “a restricted collection, for research students and medical specialists.”

I had just finished the book, and with the Wheelers’ ordeal fresh in my mind I walked into the National Museum of Health and Medicine in the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. The embryos were not on public display, so I was escorted upstairs while I pondered how much space they must need to house 10,000-plus jars of formaldehyde. Imagine my confusion, then, when my guide ushered me into a large windowless room and pointed across rows of filing cabinets. “Here,” she said, “is the collection.”

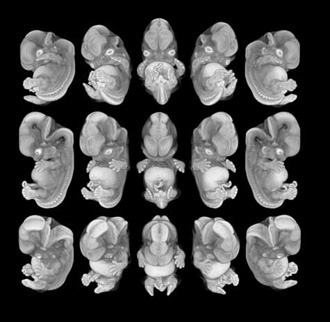

The embryo collection consisted not of whole, wet-tissue specimens as I had imagined, but of sectioned specimens. Each embryo had been painstakingly cut into thin slices, or sections, each of which was stained and mounted on a slide for viewing through a microscope.

The filing cabinets were filled with small wooden boxes, each containing several glass slides. “Here are the saggitals, over here we have the coronals, and these are the transverse sections,” my guide explained.

Because I was not trained as an anatomist, I struggled to keep up with the unfamiliar terminology. She pointed out a separate aisle of “comparative” (that is, non-human) embryo specimens, including guinea pigs, macaques, and opossums. The embryologists may have found it easy, as one of them said in 1918, to see “life in a dead section,” but I did not. I found all the information disorienting, especially in that windowless room after a late night of reading, and by lunchtime I was looking forward to a break.I had lunch with two anatomical curators for the museum. They asked about my project, and we talked about attitudes toward miscarriage and infant death in the late 19th century.

As I urged them to read Feather Crowns and gave a quick plot summary, I saw them exchange a knowing glance across the table.“Would you like to see the quints?” one of them asked.It turned out that Mason had been inspired to write Feather Crowns by an actual event that took place not far from where she grew up. On April 29, 1896, five boys—named Matthew, Mark, Luke, John and Paul—were born to Mrs. Elizabeth Lyon in Mayfield, Kentucky. The “Mayfield quints,” as they were known, did not live long; the smallest one died on May 4 and the last one just ten days later. Their mother told a reporter, “My babies were all fully developed, but they just starved to death—that and the crowd. You never saw the like of the people.”

The real Elizabeth Lyon had indeed taken the embalmed bodies on a carnival tour, but instead of running off to Washington she had taken the quints’ corpses home to Kentucky, where no one could blame her for becoming a bit unhinged. She reportedly stored them in the barn and under her bed until, old and destitute, she sold them to the Army Medical Museum for considerably less than the asking price. They were on display for several years but have now been retired to a drawer, just downstairs from the dead embryos.

The Carnegie Human Embryo Collection was designed to provide basic descriptive information about human gestational development at a time when most Americans hardly knew what embryos looked like.

The embryo collectors changed all that. With their plaster models, scientific articles, and museum exhibits, the information they produced taught us to see in embryos an image of “ourselves unborn.”And we accepted it, because we have a cultural penchant for imbuing biological events with social significance.

The embryo collectors helped to solidify the biologically based origin story we tell ourselves about how we come to be.It was an embryo-production project—an intensely gendered, often patronizing, and sometimes colonialist project that separated women’s lives, bodies, and futures from the embryo and fetal subjects that appear so independent today.

Human development is now construed as a natural process about the “facts of life,” rather than as the historical outcome of a scientific project to produce embryos and cast them as biological entities, while rendering pregnant women virtually invisible.

As new constituencies claim the right to tell conflicting stories about embryos, Icons of Life poses the question: how do we know what embryos mean?The cultural history of embryo collecting helps to explain who authored the seemingly self-standing embryos that reside at the center of so many contemporary debates.