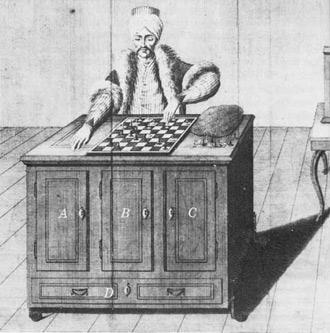

In the last weeks, I received many queries about my book due to the IBM computer Watson winning on the game show Jeopardy! over two (human) champions. I was asked about such issues as our ambivalent attitudes toward such devices as well as our hopes and fears about our fate in the age of intelligent machines. But I was also questioned about a specific eighteenth-century automaton, the so-called chess-playing Turk that was the invention of Wolfgang von Kempelen.A mechanical figure dressed in Turkish costume sat behind a box with a chessboard on top, and played against human chess players by moving pieces with its fully articulate arm.I discuss the object at some length in the book, on pages 174—183, much of it debunking false information that is out there about the object.And it is somewhat ironic that the book’s cover shows a detailed illustration of the Turk-machine as I pronounce the thing to be a “false automaton” (though the fact that a lot of people referred to it as an automaton makes it an important subject of chapter 4).I also had to defend the reputation of Kempelen from charges that he was a fraud and that his invention was a hoax. The Turk was first performed in 1770 in the Viennese court of the Habsburg monarch Maria Theresa. It was the taken on a tour all across Europe, winning matches against some of the greatest chess masters of the time, and igniting the imagination of all those who saw it perform or heard of its performance. After Kempelen’s death, its new owner took it to the United States where the Turk was also a huge success, inspiring Edgar Allen Poe to write two essays about the device. It was destroyed in a fire in 1854.As I read through numerous contemporary writings on the Turk, it became clear to me that with the exception of a gullible few, nobody thought that the thing was an actual chess-playing machine. Kempelen never claimed that he had created one. Pretty much everyone knew that the Turk was a piece of trickery and that Kempelen was issuing a challenge for people to figure out how he perpetrated the illusion that he had constructed a chess-playing automaton.Given that a lot of people were involved in the trick—read the book to figure out how Kempelen did it—it is a wonder that no one let the cat out of the bag until fairly late in the day. So the story is not about an actual automaton that could play chess, but about the cultural and intellectual reaction to the very idea of a thinking machine—despite the common awareness that such a thing was beyond the technological capabilities of the time.It did, however, inspire Charles Babbage (the pioneering designer of the early computers, the Difference Engine, and the Analytic Engine) who considered the possibility of a true game-playing machine after he played a match against the Turk. So there is that historical connection between the trick chess-player of the eighteenth century and the real game-players Deep Blue and Watson of our time.In 1893, the American writer Ambrose Bierce published a short story called “Moxon’s Master” about a chess-playing automaton that kills its creator after it is defeated in a match. This is a significant story in that this may be the first time someone wrote a story of a machine literally and intentionally killing a human being (to anticipate an objection—Frankenstein’s monster was not a machine in the original Mary Shelley novel, so not an automaton).The fascination with the automaton in the West can be described as an obsession in that it is persistent, repetitive, and charged with powerful and contradictory emotions. And the best way to dissolve the power of an obsession is to get to the bottom of its origin and essence as well to understand how it has affected the lives of those who have lived under its sway.When I was asked how I felt as I was watched Watson beat its human competitors on Jeopardy!, whether I was concerned or fascinated, I answered that I felt both. And I imagine that most people had such double reactions as well.In the book I have tried to account for why we feel such contradictory emotions when we encounter the self-moving, life-imitating machine—amusement, delight, and wonder, as well as anxiety and horror.And I show how the interplay of such feelings were articulated in very different ways throughout European history—from the concern over legitimate and diabolical magic in the Middle Ages, the question of human beings as machines or not in the Enlightenment, and the vision of human mechanization as that of both empowerment as well as emasculation in the modern era.When people talk about what will become of humanity in the age of intelligent machinery, they speak of future events as if they are already beyond our control. As if the destructive confrontation with autonomous machines, for instance, will happen to us no matter what we do.It is my highest hope that a general history of humanity’s attitude toward the automaton will inspire people to see that the future can be made according to how we decide to deal with our own emotional attitudes toward our fast-growing creations.It is not too late for us to decide what kind of a future we want to have with our artificial offspring—and start making decisions that will bring about such a future. The first step toward gaining that control is to understand the historical nature of the millennia-long dream of living machines.