Few people today except dentists will have heard of gutta-percha, but one hundred years ago it was a household word. A close cousin of rubber extracted from wild trees in Southeast Asia, gutta-percha was used for a bewildering variety of industrial and domestic uses. Gutta-percha was used for the soles and heels of shoes, roofing tiles, ear trumpets, and dental fillings (the latter one of its remaining uses today).

Gutta-percha was an example of a crucial ingredient of a high-tech industry dependent on a primitive “mode of extraction.” If rubber is natural “gum elastic,” then gutta-percha is “gum inelastic”: it won’t bounce and it’s hard at normal temperatures. However, it is eminently pliable when softened in hot water.

The Malays used gutta-percha for knife handles, whips and so forth, but it took industrial capitalism to realize its amazing potential. Gutta-percha is a better insulator than rubber and it is watertight. For this reason it was used to insulate the hundreds of thousands of miles of undersea telegraphic cables in the 19th century world: cables which were essential for European control of the far flung colonial empires.

Curiously, gutta-percha was only found in the Asian colonies; the Dutch Indies and Malaya in particular. My chapter discusses all of these matters but also focuses on the enormous ecological cost of the extraction of gutta-percha. Obtained by primitive and wasteful means from the taban tree in tropical rain forests, its extraction involved killing the trees; all for a couple of pounds of gum.

The industry was so voracious and wasteful and millions upon millions of trees were destroyed and supplies began to dry up. Eventually, methods were devised to extract the gum from plantation trees and in time gutta-percha was supplanted by plastics.

The fate of the taban trees was a harbinger of the wholesale assault on tropical rainforests today and is a paradigm of the distorted relationship between Man and Nature. Arguably, until such time as humans cease to regard themselves as conquerors standing outside of Nature, we will be condemned to repeat such errors. This exemplifies the ecological aspects of commodity production mentioned earlier.

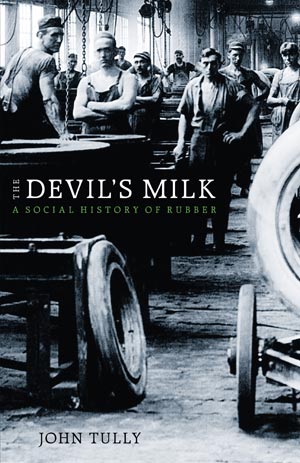

When a friend read the manuscript of the book, she commented that she would never again look at rubber the same way. In fact, like most people, she’d never paid it much attention, except perhaps when she suffered a punctured automobile tire. I hope that the book will have a similar effect on other readers.Rubber is something we cannot do without. The average automobile contains hundreds of rubber parts in addition to the tires. The electric age would have been unthinkable without it. Airplanes rely on rubber. Rubber has proven invaluable in the form of the condom in the fight against the AIDS pandemic. In short, our society would soon grind to a halt without rubber.

The story of rubber is also, for better and worse, inextricably bound up with the history of modernity. Rubber was only brought to Europe following the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the New World.Writing The Devil’s Milk also underlined for me the interconnectedness of everything in the world. It is no accident that the big rubber companies were among the world’s first transnational corporations. The story of rubber is thus an international story and it follows that the solutions to the problems exemplified by rubber can only be resolved at the level of international action.

The Devil’s Milk, I think, has significance because I have approached rubber from the standpoint enunciated by Vicki Baum. Rubber is an endlessly fascinating substance, but the history of what it has done to human beings in forests, plantations and factories is more fascinating still.

My approach follows Marx’s analysis of commodities as things with a dual nature. Like Marx, too, I like to think that progress towards a more humane and rational use of that commodity can come from that contradiction. The very first bill signed into law by the incoming US President Barack Obama resulted from a long campaign waged by a retired rubber worker.