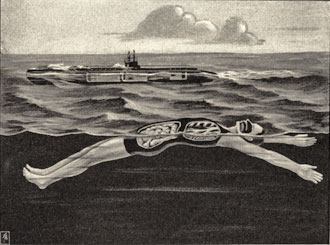

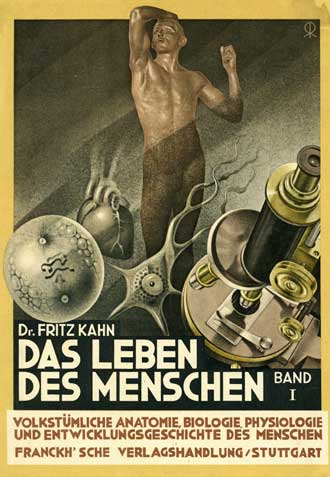

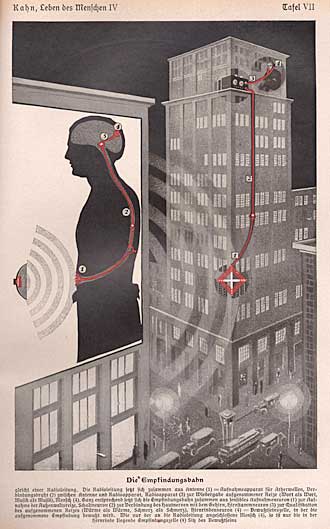

Scholars have long debated modernity, its origins, and its defining characteristics. Body Modern sidesteps those questions. Modernity, it argues, did not descend upon the world like a deus ex machina that re-ordered human consciousness and changed everyone and everything. Instead, Body Modern treats modernity as a historical artifact, the core concept of a 20th-century identity formation.What makes that tricky is that modernity was a capacious signifier, full of paradoxes. It could absorb anything that seemed to oppose primitive humanity or longstanding tradition, but also anything that opposed the recent past, especially passé versions of the modern. Even the primitive could serve as a signifier of the modern, if it was reframed as a critique of the no-longer-fashionable present, and served up as the latest thing. The modern had to be new.In the middle decades of the 20th century, a critical mass of people took themselves to be moderns, living in modern times, and felt impelled to live and perform the modern. They sought to cast off local identities and revise traditional ways, to differentiate themselves from what came before. They did that by talking on the telephone, driving cars, wearing modern fashions, reading modern illustrated magazines, listening to new kinds of music on the radio and phonograph, doing new kinds of dances, receiving modern medicines and treatments, going to the movies, taking up new political ideologies, and doing a million other things that signified modern-ness. There was a nearly inexhaustible demand for modernizing devices, objects, methods, presentations and experiences. The public thirsted for the modern.In this environment, Fritz Kahn pioneered a new kind of image: illustrations that were scientific, metaphorical, and self-consciously modern. In a hyper-illustrated age––where the very abundance of printed half-tone images was itself a signifier of modernity––Kahn’s books on the science of the human featured thousands of illustrations in a variety of modern styles and techniques: surrealism, Art Deco, photomontagery, Bauhaus functionalism, abstraction, Neue Sachlichkeit, sequential art, everyday commercial illustration, etc.It was a novel and iconophilic approach to popular science, inspired by the media, styles, and genres of the time, especially the illustrated newspaper and magazine. Materials that could help people acquire and perform a “modern” social identity were in demand. Kahn presented himself as an impresario of the modern, a provisioner of images to get modern with. His images were a visual rhetoric of modernity, full of representations of science and technology. More than that, the images themselves worked as a kind of a technology of the self, a modern rhetoric of visuality, which naturalized modernity by situating it within the human body.