When I first heard about the lawsuit, it resonated with me in many ways. I am an art historian, I had been a Getty Fellow, and the Armenian Genocide is part of my family history. As the lawsuit was winding its way through legal procedures and court filings in Los Angeles, I decided to go on a quest, to retrace the steps of the Zeytun Gospels, from the site where it was created through all the known stations on the journey that eventually took the manuscript to Yerevan, Armenia, minus its eight missing pages that ended up in Los Angeles.

I hoped to gain a fuller understanding not only of the manuscript itself and of its history, but also of the places, landscapes, and even ruins where the Gospels had spent time during its itinerary. I hoped to learn something of how the Gospels and its communities had interacted in specific places, and how the genocide and its long-term effects had transformed these sites.

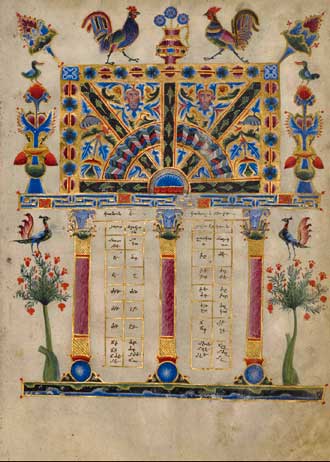

The book is structured along this “quest,” where each chapter considers a city or site where a key moment in the manuscript’s life unfolded. In the overall arc of book, the central character is the Gospels. Yet each chapter can stand on its own. Those who are passionate about medieval sacred objects can delve into the chapter on Hromkla, the castle on the Euphrates River not far from the Mediterranean, where the artist Toros Roslin created the Zeytun Gospels for his patron, the Catholicos of the Armenian Church, the great bibliophile Constantine I.

Those who want to know more about the genocide and the destruction of culture will be drawn to the chapters that retrace the steps of the holy book through some of the most terrible atrocities of World War I and the Armenian Genocide. And those who love courtroom dramas and restitution battles can focus on the final chapter on Los Angeles, that follows the lawsuit and its players and places it in the context of the restitution movement for the Armenian Genocide, which was modeled in many ways on the recent wave of Holocaust Restitution.

Even the book’s illustrations are carefully curated and sequenced to tell a stand-alone story through narrative captions.

The last decade has seen the transformation of the public debate about cultural heritage, art and its intentional destruction, the responsibilities of museums, and the challenges of restitution. The Missing Pages builds on these debates. It uses the litigation in Los Angeles and the gripping story of a single manuscript, to delve into these complex and overlapping issues in a substantive way.

Questions of restitution will likely increase and become more pressing worldwide in the future. I believe we will see more struggles between powerful institutions and communities over the control of cultural patrimony. American museums have already had to change the way in which they react to these challenges — the public today is showing little tolerance of the condescending, tone-deaf, and Eurocentric attitudes that used to be common. Many tensions remain, however, as we are seeing in the debate on the proposed restitution of African art held by French museums that is unfolding now. I am heartened to see that some museums are taking proactive steps towards the whole issue of restitution; they are making great efforts at being inclusive and approachable, even decolonial, and some art museums are even integrating painful histories into their exhibitions in innovative ways. However, we still have a long way to go.

The book, I hope, will prompt deeper reflection and action on cultural heritage and human rights, as well as on the whole issue of restitution and reparation at all levels. There is no one-size-fits-all model. In the case of the Zeytun Gospels, a settlement was reached in 2015. The Getty acknowledged the Armenian Church’s historical ownership of the pages, and the church donated the pages to the Getty Museum. The ownership is acknowledged, the pages are preserved, and they are available to the public to view in Los Angeles, where as many as 500,000 people of Armenian extraction live, many of them descendants of survivors of the Armenian Genocide. In this case, both sides made concessions, and both sides achieved some of their original goals. The art press hailed the settlement as an important precedent in disputes between museums and religious communities.

However, it is also critical to acknowledge that there are tremendous asymmetries of power and that restitution and reparation are very difficult to achieve in most cases. For the Zeytun Gospels, there could not be a return to the past, and the injuries of war and genocide can never be repaired. Ultimately, the greatest impact of settlements like this is that they help develop greater collaboration between museums and communities over the appreciation of works of art and the telling of difficult histories.