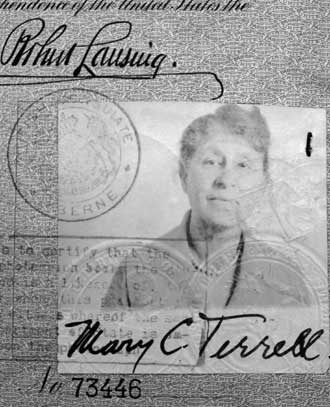

It is difficult to crack open this book to a particular page and get a strong sense of the whole. Individual chapters highlight the activism of varying groups of women in different national and international arenas. Initially, many of these women labored in isolation from one another. Over time, though, they would meet. In the aftermath of 1919, as chronicled in the book’s epilogue, most would begin to collaborate as they came to view their own push for gender equity as a part of a broader, global struggle.A “just-browsing” reader who likes to start at the beginning would make the acquaintance of Marguerite de Witt Schlumberger, a French grandmother who sent five sons to the trenches. Schlumberger organized Western suffragists in Paris to demand that women be seated at the negotiating table. A bit further on, in Chapter 2, a reader’s gaze might by drawn to the 1919 passport photo of Mary Church Terrell, an African American daughter of once-enslaved parents and prominent civil rights activist who came to Paris to champion both racial justice and gender equality. Both she and her college roommate, Ida Gibbs Hunt, were active players in 1919, helping to put pan-Africanism on the ideological map.The opening lines of Chapter 3 offer an equally enticing introduction to the book. There a reader would encounter Egyptian feminist Huda Shaarawi as she stares down British colonial authorities, daring them to make her a martyr in the fight for Egyptian sovereignty and universal democracy.Chapter 4 delivers its own share of drama as German feminist Lida Gustava Heymann publicly embraces French feminist Jeanne Mélin. Mélin’s family brickmaking factory was occupied and dismantled by the German army in 1914, and she lived out all four years of the war as a refugee. Her symbolic reconciliation with the “former enemy” would inspire hundreds of pacifist women at the 1919 WILPF Congress in Zurich to stand and take a public oath “to made good the wrongdoings of men.”It is tempting to recommend opening the book to Chapter 6. There a reader would learn how it is that working women, many born in desperate poverty, managed to convince the nascent International Labor Organization to call for a minimum global standard of twelve weeks paid maternity leave (a standard the United States has yet to meet today).In the end, however, if I had to send a browsing reader to one place in the book, I think I would point to the middle of Chapter 5. There she or he would meet Soumay Tcheng, the sole woman appointed as an official delegate to the Paris Peace Conference, as she holds the Chinese foreign minister captive at the point of a “rosebush gun” in order to prevent him from signing the Versailles Treaty. To find out if Tcheng was successful or not, the reader would either need to settle in for a long afternoon of browsing or buy the book.Reading Peace on Our Terms, readers may find themselves justifiably shocked at the contemporary relevance of women’s priorities a century ago. Here in the United States in the early twenty-first century, women’s marches, the #MeToo Movement, and the Equal Rights Amendment are all front-page news, while #BlackLivesMatter and other social justice movements highlight the voices of women of color. Globally, female prime ministers head governments from New Zealand to Finland and from Slovakia to Ethiopia. Since 2010, at the United Nations, UN Women has directed efforts to promote global gender equality and to demand a role for women in peace processes.If female politicians and peacemakers have never been so visible, myriad problems stemming from gender inequality have proven stubbornly intractable. Violence against women, marriage of under-age girls, sexual discrimination in the workplace, and unequal representation of women in all levels of government continue to sow instability and poverty at home and around the world.The women featured in Peace on Our Terms fought for women’s full inclusion in peacemaking, nation building, and international policymaking for a reason. They saw it as a necessary precondition to combatting the discrimination and insecurity that had long defined their lives. That battle continues unabated today.I hope that readers will be inspired by the courageous women’s rights activists in this book. These women—all of them—defied convention and put their reputations, if not their lives, on the line. They did so because they believed that women not only had a right, as individuals, to shape their societies, but they also had a duty, as women, to speak from their unique life experiences. From Malala Yousafzai to Greta Thunberg, we see women around the world continuing that tradition today, often unaware of the shoulders they stand on.I also expect—perhaps even hope—that some of my readers will step away from this book a bit angry. “How,” they may ask themselves, “can we still be fighting so many of the same battles as these women a century ago?” To ask such a question is to probe the tremendous hurdles women faced in the early twentieth century, as they fought to establish a place for women in international diplomacy and policymaking, and it is a first step toward continuing to fight for a more just and equitable world today.