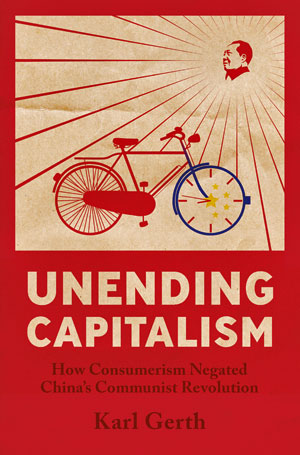

My book invites readers to contemplate the larger significance of easily overlooked mass produced things. If they were to skim the book, they would encounter dozens of photos and illustrations of such things. I use these images to provide an accessible entry point into the arguments of the book.For instance, I include photographs of people wearing wristwatches and an illustration of someone on a bicycle. Such illustrations showcase the spread of consumer desires for industrially produced consumer products and document how the state both deliberately and inadvertently contributed to building consumerism and negating the Communist Revolution. After all, not everyone was able to obtain the three most sought-after items of a wristwatch, bicycle, and sewing machine at the same time. The distribution of these things created and reinforced the inequalities associated with industrial capitalism. Conveniently for the researcher, these sources were easy to find. People remembered their acquisition—or not—of these things even more clearly than more high-profile national events in the era.I also include many photographs of Mao badges because China experienced the largest consumer fad in history when the country produced billions of badges of Chairman Mao for people to wear over their hearts during the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s. The badges were produced in thousands of varieties, sizes, images, and materials.

The assortment depicted above includes a glow-in-the-dark badge in the lower right as well as, above it, Mao looking right, a potentially risky image for the maker for suggesting Mao was endorsing right-wing politics. Who got the latest, biggest, and most desirable badges reflected the growing material inequalities accompanying industrial capitalism. I use these images to illustrate the three defining aspects of a spreading consumerism: the unprecedented scale of industrial production of consumer products, the spread of discourse about such products in mass media that taught people to have new needs and wants, and the growing use of products, including badges, to create and communicate different, often hierarchical, identities. Even Mao and Zhou Enlai saw the badge fad as creating the opposite social values from the socialist ones intended.I have no doubt that many also felt they were demonstrating loyalty to Mao and faith in the Revolution. But their action (using badges as a substitute currency, collecting them to demonstrate connoisseurship and connection, and countless other uses) had a larger impact. The badge fad—and indeed most activities associated with the Cultural Revolution such as house ransacking and student travel throughout the country—facilitated the “negation” of the Communist Revolution by expanding desire to use mass produced products for social differentiation. So, the badge fad helped manifest the expanding inequalities of industrial capitalism.

These are just two examples of the many aspects of consumerism illuminated by the illustrations. I also include advertisements from the era because few associate advertising and other forms of product promotion with “Maoist China.” And I do the same by highlighting periodic state promotion of clothing fashions. Likewise, I included photos of department stores and service workers to discuss how consumerism operated in retailing. Though such commonplace topics, seldom included in standard histories of the Mao era, we can reconsider the larger history of the era.I hope my book helps readers reexamine a familiar history of China, and indeed the world since the Second World War. In my book, many famous events such as the Mao badge fad take on different meanings. In doing so, I invite readers to reconsider the history of capitalism through its relationship to consumerism.

My analysis suggests an ongoing need to move past Cold War-era binaries—a world we still imagine was divided between planned economy vs. free markets, dictatorship vs. democracy, interests of the collective vs. freedom of the individual, and public vs. private enterprise. Unending Capitalism suggests that these dichotomies may have become so politicized and inaccurate that they hide more than they reveal.

What emerges is a state capitalism that shifted back and forth along various points on a state-to-private spectrum of industrial capitalism, each permutation affecting consumerism in a different way. During the late 1950s and late 1960s, the political economy moved in the direction of state-controlled accumulation, whereas during the early 1950s, early 1960s, and 1970s the political economy shifted toward market-mediated accumulation and consumerism. These shifts were justified as a necessary part of Communist Party efforts to “build socialism” in order to reach communism. But the existence of such shifts reveals that neither the state’s vision of socialism nor its practice of state capitalism and consumerism were static.Demonstrating that the terms state capitalism and state consumerism refer not to a fixed but rather to a fluctuating point on the state-to-private spectrum of industrial capitalism provides a reminder that all economies mix elements of institutional arrangements associated with both ends of the spectrum. All forms of industrial capitalism involve attempts to manage consumer desires.Viewed from this perspective, the “market reforms” since the death of Mao in 1976 that promoted greater consumerism in China appear to be less of a break with Maoist ideology and policy and more as yet another shift in state-led capitalism.

Such shifts also suggest that, aside from state capitalism and private capitalism, there are other varieties of capitalism in between these extremes.I hope that expanding the study of the varieties of capitalism to include “socialist” countries such as China presents an opportunity to render the history of capitalism and consumerism as more truly global, and to think of the Mao era as part of an integrated world history rather than an isolated and exotic “socialist” interlude.