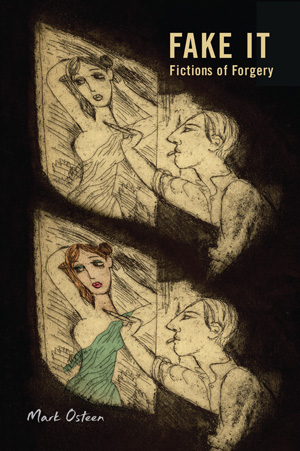

A browsing reader would note that the book is a feast for the eyes. It includes twenty-seven images of paintings, movie stills, and art installations ranging from the Early Modern period (Bosch, van Eyck) to Picasso and Louise Bourgeois, each one depicting a forger, a work discussed in the text, or a forged work. In the e-book, these images are in color!

A reader with a bit more time might start with the introduction, where I lay out my broad case and present the fifteen theses to which I refer throughout the book. That reader would, I hope, be encouraged to peruse the first chapter and follow Chatterton, a cheeky youth who, at the age of sixteen, created an entire fictional history furnished with dozens of poems and documents and a fake poet/scholar/priest author.

After his death (probably accidental) at seventeen, his life and work inspired a generation of poets. An enterprising boy who used his fictional avatar to create an authorial identity, Chatterton carried with him a charismatic aura of doom that authors such as Coleridge, Wordsworth, Browning, George Meredith and Oscar Wilde found both vexing and vital. Chatterton was, in many respects, the first pop star.

That reader might also enjoy chapter six, which brings together Welles, real-life art forger Elmyr de Hory, and Clifford Irving, who, after writing a book about de Hory, perpetrated the infamous fake autobiography of Howard Hughes. De Hory and Irving succeeded at first because they were so audacious, but also because many people secretly root for anyone who tweaks the pretensions of the artistic and literary elites. That’s why forgery is often deemed a “sexy crime.” In the film, Welles describes himself as a faker (remember his War of the Worlds hoax?) and further declares that all artists, including Picasso, who plays a secondary role in F for Fake, are fakers—and that there’s nothing wrong with that.

This chapter again borrows from the subject it discusses, here using film terms—e.g., flashback, freeze-frame, etc.—as subheadings and employing a collage-like structure that mirrors Welles’s cubist portrait of the artist as forger.

But the chapter I most enjoyed writing was the one about Erasure, not only because of the novel’s incisive satire and wit, but because I treat the book as a jazz text. Why? Well, the fictional novelist is named Thelonious, after the iconic jazz musician Thelonious Monk, a parallel that gave me license to pair Monk’s life and art with those of his fictional namesake. Thus, I insert vignettes from Monk’s life into my discussion of the novel and use Monk’s song titles as chapter subheadings. The text’s playfulness inspired me to “play jazz” on the page.

I hope that Fake It spurs scholars, artists and writers to rethink their attitudes about forgeries and to recognize the many gray areas involved in creative production. I also hope, perhaps quixotically, that the fifteen theses will serve as both a group of guidelines and a posse of provocations that will prompt others to rebut or reinforce them.In addition to the tropes and themes outlined above, one pattern I noted repeatedly is particularly relevant to the contemporary world: how credulity is persistent and contagious (thesis 13). Even when the duped are shown that they’ve been hoodwinked, they cling to their belief against reason; such credulity spreads in groups like a virus.

We have seen countless examples of such “thinking” in the past few years.In addition to offering new looks at texts by well-known artists such as Peter Ackroyd, Peter Carey, Everett, Gaddis, and Welles, I also seek to draw more attention to the novels of Phillips and Hustvedt, and to the work of nearly forgotten writers such as Margaret Cavendish, George Meredith (and his wife, Mary Ellen).Finally, I hope that, unlike most academic monographs, Fake It provides entertainment! I intentionally wrote it in a non-academic style (one anonymous reader described it as “breezy”) that displays wit, creativity, and humor. I eschewed jargon and academese to appeal to a broader public and to model the truth that we academic writers don’t have to be incomprehensible or dull to create serious criticism.