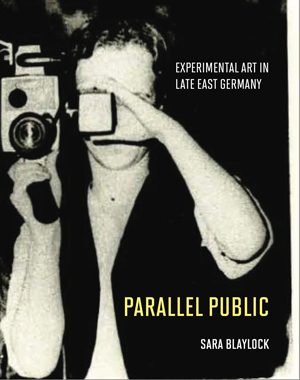

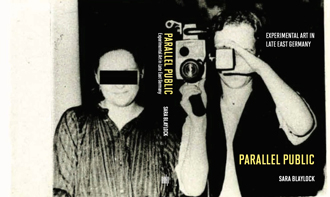

In fact, I’d want the reader to really take a good look at the cover of the book. The photograph comes from a Stasi surveillance file of a groundbreaking art event named Intermedia 1, which though organized independently took place at a state cultural center in 1985. The location benefitted the project; hundreds of people attended Intermedia 1 and dozens of artists, filmmakers, and musicians showed their work. It was a defining moment for many people in the GDR, a summit that brought people together in quantities never before seen.Turning back to the cover, you can see in this image that the Stasi mole (a so-called “unofficial collaborator,” so not a person who actually worked for the Stasi in an official capacity) was friendly with the people he photographed. (My gendering of the spy here is intentional; most people involved in the Stasi were men.) The camera operator is playing around with the person capturing his image; what we see is a kind of playful camera-on-camera moment. The woman, who you see on the back cover is smiling at the camera. Importantly, neither the man or woman in the photograph would have known that the person taking their picture was doing so on behalf of the Stasi.We see a man and woman engaging with their observer, a Stasi informant who was not only an acquaintance, but a friend worthy of not just a smile, but a kind of joke, a recording in double. This image resonates with me, a reminder of both the intractable quality of state authority, its tactics always adapting, but also the intractable quality of experimental artists, whose tactics too were always adapting, that is to say, relentless.The photograph in many ways encapsulates the argument of the book, at least in relation to state power. For anyone inspired to look at the origin of the photograph, please now turn to Chapter 5, which uses the Intermedia 1 festival both as a means to highlight the way that interdisciplinary artistic practices figure in East Germany’s larger (namely ideologically motivated) art history. The festival also marks a turning point in the ways that artists worked to bring their work to broader audiences.

The history explored in Parallel Public stands on its own merit, even if it has scarcely been explored previously, especially in the English-language context. I should note that even in Germany, the approach I take, which unites a multiplicity of sources and examples that have not been previously studied together, is likewise pretty unique. Extant studies have also presented the GDR’s artists in divisions based on region, gender, and/or medium. The experimental artists of the late GDR were committed to working autonomously and without fear of recrimination from a government that had historically not been very generous with citizens who refused to conform. It is inspiring to read about their efforts, both on an individual and a cumulative level. We can see from this history that persistence, in this case a demand for artistic freedom, can lead to tangible change even in the most intransigent of contexts.The ways that these artistic practices could build community or bring greater representation to marginalized subjects translates to efforts that have been significant to art histories since the 19th century. The absence of these stories from a global history, especially in relation to post-WW2 art histories which have been so readily explored using American or Western European examples, reflects not the value of the art, but rather the prejudices that continue to skew people’s impressions of life in the Cold War East.Importantly, by the Cold War’s final decade, the East German government’s inability to produce a collective public significantly frayed its power. The work of experimental artists was not only an antidote for, but also a diagnosis of a weakening state: a foil and a mirror to official culture. The GDR’s experimental scene produced an alternative public—a parallel public—with commitments to culture, community, and interdisciplinarity that state socialism had sought, but failed to inspire. This irony, really an inversion of state socialist principle, lies at the heart of this book.