The way in which the French related to the world outside is dealt with less as foreign policy than as ways in which French travellers discovered and commented on foreign countries and people. In the chapter ‘France in a foreign mirror’ you can see what the French thought of America: Chateaubriand, who went there in 1791, fantasised that it was still in a state of nature. Lafayette, who had fought alongside the Americans in the War of independence, returned there for a victory tour in 1824 and praised it as the land of liberty. The much younger Tocqueville came in 1831 and admired American democracy, but was also concerned that it might end of as ‘the tyranny of the majority’ and did not understand how the American passion for equality could allow slavery.Alternatively, turn to chapter 8, ‘War and Commune, 1870-1871’.

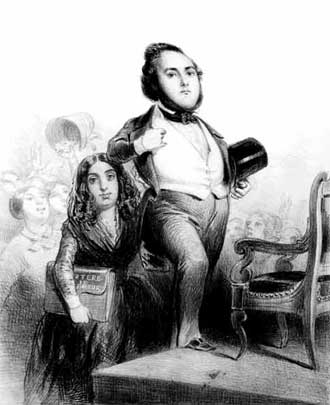

This describes the siege of Paris by German armies during which the population was reduced to living on elephants from the zoo and blackbirds, then rose against the government that wanted to surrender to the Germans, an insurrection that was put down with the loss of 20,000 lives.Turn to the conclusion. This begins with the death at the battle of the Marne of poet and intellectual Charles Péguy. He had made his name during the Dreyfus Affair when the France of the rights of man locked horns with reactionary, anti-Semitic France. He represented the new France, republican, socialist, enlightened, but he also loved the Catholic faith, symbolised by the cathedral of Chartres, and French history, incarnate in Joan of Arc. He was killed, stupidly, standing up in his blue coat and red trousers, urging his men on. And yet he represented the coming together of many Frances which had so long been in conflict, in a patriotic gesture the like of which would see the country to victory in 1918.Don’t miss the illustrations: sixteen plates and 43 images of celebrities staring from another era, following the shift from painting to photography. Paris as slum-land, imperial capital and battlefield, the social elite and striking workers, holidaymakers in Normandy and Louis Renault in one of his new cars.

The story comes to an end on the battlefields of northern France. The history of France in the twentieth century was not so happy. France was briefly occupied by Napoleon’s conquerors in 1815, and by the Germans in 1870-71, but was defeated and occupied for four years by the Germans of the Third Reich in 1940-44. The republic founded in 1870 was destroyed, the anti-Semitism that had flared up during the Dreyfus Affair ended up with the deportation of a large number of French and foreign Jews to the death camps. It took de Gaulle to drag France out of this mess, founding a republic in which the president had much greater power, and asserting France’s greatness by withdrawing the country from the military side of NATO.

Children of the Revolution is about a much more positive period in French history, when the French managed to combine ideological battle with political compromise, religious strife with toleration, artistic and literary genius with education and culture for the masses, gay Paris with a passion for the countryside, feminism with family life, national greatness a love of peace and the feeling that at least they did not have to work as hard as the British.If you are fed up with yet another book on Hitler or Stalin, the Russian Revolution or Nazi Germany, this will make a refreshing change.