Over the past decade, a series of books has examined women’s claims to urban space at the turn of the twentieth century as integral to the rise of the modern city. Most such accounts have been written by scholars of urban literature and social historians. The topic has been broached rarely by architectural historians, with the result that buildings have largely dropped out of consideration in analyzing how women created a public presence for themselves in the modern city.

As an architectural historian, I seek to refocus attention on the built environment, particularly on the importance of architectural language, in the gendered appropriation of urban spaces. Paying close attention to the choices made by builders and patrons, I demonstrate how women in Berlin employed architectural language to create specific and meaningful identities for themselves as public citizens. Architecture became a medium through which women expressed contested notions of modernity in a language shared and understood by Berliners.

Reading buildings as carefully coded texts, I hope to make apparent the significance of visual and spatial representations to marginal urban populations seeking a metropolis that recognized and accommodated difference.Architecture does more than signify, however, and I am equally concerned with understanding how it reshaped gendered experiences, particularly the experience of the public sphere.

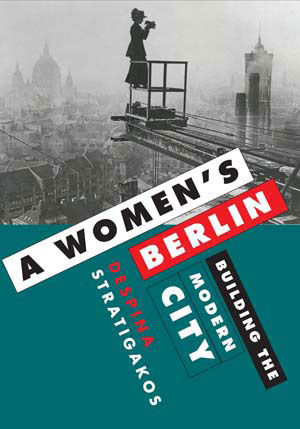

A Women’s Berlin pays special attention to monumental projects, such as the Victoria Studienhaus, a residential center for university women that was designed by Emilie Winkelmann and created a new model for the German academic experience. Monumentality challenged cultural precepts that forbade “respectable” women to be visible in the city. Big buildings constituted an explicitly disruptive urban presence, boldly refuting traditional conceptions of women’s proper place.

Their monumentality declared that women would not be contained but would instead expand upward and outward into the public spaces of urban life. This desire to express one’s modern identity through buildings also suggests a very different strategy from that adopted by the flâneur.

The phenomenon of women building their modernity into the very fabric of the city underscores, as sociologist Janet Wolff has argued about literature, the insufficiency of notions of subjectivity that emphasize disembodied engagement or ephemerality as a universal response to the experience of modernity, a position exemplified in the writings of urban commentators such as Georg Simmel, Karl Scheffler, and Hans Ostwald.

These male critics, lamenting the instability of modern life, voiced one reaction—to be sure, shared by many Wilhelmine Germans—to the capital’s unruliness. Not all Berliners, however, took a pessimistic view of urban dislocation. Seeing the familiar landscape of the city vanish under the onslaught of industrial urbanization, many women glimpsed their liberation and joined the fray, helping to construct the new Berlin with the zeal of the converted. As visionary builders, constructing an alternative way of being in the city, Berlin women rejected a homogenizing view of modernity and defined their experiences in relation to the concept of difference.

A Women’s Berlin seeks to understand how they marked difference in spatial and architectural terms. Surprisingly, the rise of a more explicitly gendered landscape undermined the fixity of separate spheres for men and women, a model that historians and political theorists reject as simplistic and misleading. Instead of presenting us with a clear and deep divide, a women’s Berlin proves both more permeable and edgier: Women pressed against traditional boundaries, crossing over into a “man’s” world, while also erecting new barriers that protected and nurtured their evolving urban identities.

The Victoria Studienhaus, which allowed women to participate more fully in German academic life, but on their own terms, is an apt example. Such architectural interventions pursued neither integration nor separation but something more fluid and dynamic.