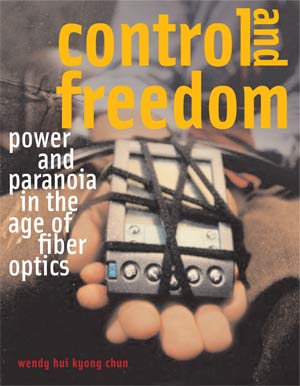

This book focuses not only on questions of sexuality, but also race. Race, Control and Freedom argues, was, and still is, central to conceiving “cyberspace” as a utopian commercial space. To exaggerate slightly, without race, there would be no cyberspace, either fictionally or factually, for it is through representations of raced others—“high-tech Orientalism” and “scenes of empowerment”—that one of the most compromising forms of communication has been bought and sold as empowering. Cyberpunk fiction, which spawned the term “cyberspace” and the desire for it, is filled with techno-Orientalist images of a dystopian yet sexy future in which console cowboys navigate and dominate. A conflation of racial with technological empowerment also helped transform the Internet into a utopian, have-to-have technology, for through this conflation, technology—condemned by liberals during the 1980s as part of the problem (nuclear proliferation, etc.)—could be embraced once more as the solution to our political problems. The Internet was sold as a solution to discrimination, as a utopian escape from the everyday.During the mid- to late- 1990s, almost every Internet advertisement featured happy people of color, who claimed that the Internet was a race-free utopia. According to these “scenes of empowerment,” for instance MCI’s “Anthem” commercial, the Internet was an ideal space in which bodies—and thus the discrimination that stemmed from them—disappeared.This multi-cultural hype was hardly anti-racist. The message behind these commercials was not even “do not discriminate,” but rather “get online, if you want to be discriminated against.” These commercials also relied on a certain racist knowledge: of seeing and knowing immediately, of course these people would be happy to be online. Further, they hardly offered an accurate representation of Internet demographics. The point was not to represent the Internet as it was, but rather to transform the Internet into a wonderful, enticing space that everyone had to have, that one could not not want. Tellingly, these commercials stopped running in 2000 in the United States. By then, many more Americans were online; these commercials, though, were still run in Japan, where Internet usage was low.Importantly, this racial utopia rhetoric combated the dominant early- to mid- 1990s paradigm of the Internet as a pornographic, dangerous space. In 1995, for instance, the film The Net portrayed sending one’s credit card over the net as an invitation to murder and the media was flooded with articles about cyberporn and cyberstalking. To lure people online, telecommunications companies—such as MCI and Cisco Systems—flooded the airwaves with happy commercials. But those commercials were not just celebrations: they also contained a paranoia-inducing threat, the threat of being left behind by those others who were already online and reaping the benefits.Of course, race has never been absent on the net, and the Internet proliferates race as a database / consumer category. This proliferation of race, however, is not just a problem, but can also lead to important discussions about race: its possibilities and limitations. Groups such as Mongrel have produce software that plays with racial categorizations in order to get us thinking about the convergences between race and technology. (Their Heritage Gold software program is a beautiful hack of photoshop.) Gregory Pak’s film Robot Stories also plays with the racist formulation Asians=robots to create an intriguing future in which the creativity, humanity and inhumanity of robots and humans flourish together. The point, in other words, is not to run away from race or technology, but to rework it to enable different possibilities and futures.Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics argues that we need to engage the ways in which the Internet compromises our privacy or dream of impossibly secure systems in order to understand how it can enable a freedom that cannot be controlled. Because freedom is a fact we all share, we have decisions to make. Freedom does not result from our decisions, it is what makes them possible. This freedom is not inherently good, but entails a decision for good or for evil. The gaps within technological control, the differences between technological control and its rhetorical counterpart, and technology's constant failures mean that our control systems can never entirely make these decisions for us.We must take seriously the vulnerability that comes with communications—not so that we simply condemn or accept all vulnerability without question—but so that we might work together to create vulnerable systems with which we can live.