While The Quantum Frontier is not a single-topic book, perhaps no question has received as much attention as that of the enigmatic Higgs boson. This undiscovered particle is always mentioned in the thousands of articles describing the LHC that appear in newspapers and popular science magazines. But precisely what this particle is, and why it’s important, is not always talked about. That’s a shame—without this particle or something equivalent, the universe would be a very different place.

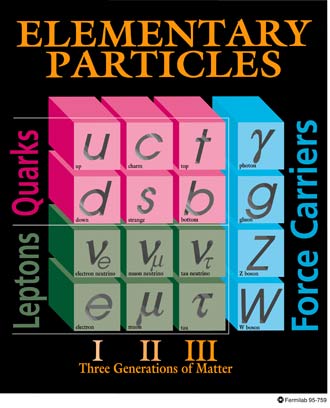

The last couple of decades have taught us that the matter of the universe is made of unfamiliar subatomic particles called quarks and leptons. Two kinds of quarks (confusingly called up and down) make up the protons and neutrons of the nucleus of atoms, while the electron is the most familiar lepton. There are two carbon copies of these particles and all of the particles have radically different masses. The very light electron (the lightest of the class of particles that takes its name from leptos, the Greek word for light) has a mass of 0.05% that of a proton, while heaviest of them all, the weighty top quark (a copy of the up quark) has a mass 175 times heavier than the proton. Why should this be?In the 1960’s, theoretical physicists were able to invent sensible theories that could predict many of the phenomena we observe. However these theories required subatomic particles to be massless—a distinctly not sensible idea.

To return sense from nonsense, a proposal was put forth in 1964. Peter Higgs integrated some earlier ideas with his own and suggested that there might be a previously-undetected energy field in the universe which has come to be called the Higgs field.It is not obvious how the Higgs field can result in a particle, but a water analogy may help. Water is a liquid and fills up all of a container in which it is placed. One might call water “continuous,” as it is not at all trivial to go into a pool and find space “between water.” And yet water is made of molecules consisting of two hydrogen and one oxygen atoms (H 2 O). Water consists of tiny “smallest bits” of water and still looks continuous when viewed at human-size scales.Similarly, the Higgs energy field consists of countless Higgs bosons. Finding such a boson is a crucial test of Peter Higgs’ idea and it is this search that is the most reported of the many things the LHC scientists are looking for. Reading The Quantum Frontier should give a very good idea of how scientists will know when they’ve found one. (If, indeed, Higgs bosons are there to be found at all.)Most books on physics written for the public concentrate on “big ideas” totally forgoing the common question “Yeah, but how do they know that?” That’s where The Quantum Frontier comes in. And while we all must trust experts at some level, it’s comforting to understand why it is that scientists have the confidence that they do. I hope that reading this book will enable a non-scientific reader to understand the principles that govern the LHC accelerator and the detectors that record the data. The experience should be like that of getting a glimpse under the hood of an exotic European race car.I am sometimes asked why I write books for the public, when the time could be used more profitably to do research. It is a duty, indeed a privilege, to be able to share the excitement of frontier science with the general readers who are interested in the subject. There is another audience I have in mind as well. My path was not an obvious one, for neither my mother nor my father are scientifically-inclined. I am very grateful to my truly-wonderful parents. But they could not provide the kind of scientific role models some of my colleagues enjoyed in their childhoods. To indulge my youthful scientific curiosity I read. Prodigiously.

Nothing was exempt, although science fiction was my passion. As I got older, I was introduced to writings by Carl Sagan, and to Isaac Asimov’s popular science books, and to George Gamow. I was hooked… Science fiction is bound only by the writer’s imagination and the reader’s credulity. In science though, there is an answer. It is the universe itself.Since then, I have devoted my life to the grand study of the cosmos—an endeavor that has spanned human history and will continue long after I have breathed my last. The science that I read now is more technical than what I read decades ago. But the spark started then, with the popular writings of a few who may have known of the impact they would have. Somewhere out there, there are potential young scientists, needing a similar kind of introduction to find their true calling. I write for them.