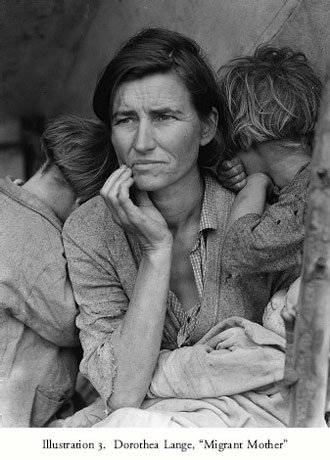

In all of my books, my chief purpose is to examine the ways in which history and imaginative works can illuminate each other. How do the events of a particular time and place shape the novels, stories and visual art of that historical moment? And how in turn can those fictional works help us understand our national past?The Depression years provide an especially promising period for examining such questions. Because of its scale and persistence, the economic trauma affected large numbers of Americans directly; and virtually everyone followed the course of events through coverage in the nation's newspapers, magazines, radio broadcasts, and movie newsreels.The key point I demonstrate is that Americans responded in a wide variety of ways to this shared crisis. A recent review in the New Yorker characterized the book aptly as offering “a corrective to the assumption that the Depression decade was dominated culturally by leftist aesthetics and politics” and as revealing “fascinating vicissitudes of art and history" (The New Yorker, March 30, 2009).In short, The American 1930s offers a revisionist history of the art and literature of the 1930s. The case studies I present accurately reflect the yeasty and complex responses that Americans displayed to the turmoil of the period. Some Americans recoiled in disappointment and anger, and called for revolution. At the same time, others embraced all the more fervently the essential rightness and continued relevance of traditional national propositions.Every revolutionary manifesto can be matched by a call to re-affirmation. In 1932, Malcolm Cowley, Langston Hughes, Edmund Wilson, and the other intellectuals who published Culture and the Crisis demanded a revolution and supported William Z. Foster, the Communist candidate for president. A couple of years later, on the other hand, regionalist painter Grant Wood, in his Revolt Against the City (1935), argued, “during boom times conservatism is a thing to be ridiculed, but under unsettling conditions it becomes a virtue.” Wood detected, in the opinion of writer Steven Biel, a “powerful yearning for security” as the dominant mood of the time.Those diverse understandings led to diverse imaginative expressions – in effect a debate over the meaning of America. The task I have taken up is to provide a through line for exploring that rich heterogeneity, by tracing one of the main subjects to which the decade’s writers turned again and again: the past. The writing of the 1930s comprises an extensive and complex engagement with the past, in myriad forms: the memoirs and biographies of influential individuals, and the factual and imaginary histories of the United States and other nations.Let me give a few examples. Several of the popular biographies of the 1930s – including some of those that won Pulitzer Prizes and other awards – recreated the lives of earlier Americans as a way of making a statement about the turbulence of the Depression years.Marquis James’s two-volume biography of Andrew Jackson, for instance, presented the seventh president as a protector of ordinary men and women against the power of early nineteenth-century bankers. James explicitly invokes the parallel with Franklin D. Roosevelt and his struggles with what he called “the economic royalists” of the 1930s. Carl Sandburg’s monumental, six-volume life of Abraham Lincoln also rhymed with the thirties: Lincoln was the plain man, the man who had grown up in poverty, and whose example should inspire a later generation to rely on the genius of democracy to find solutions in hard times.Many of the decade’s novelists also used historical subjects to comment on present discontents. Kenneth Roberts wrote several bestsellers set in and around the Revolutionary War. Adopting a pro-British point of view – Benedict Arnold is the hero of several of the novels – Roberts indirectly took his stand on the politics of the 1930s: a fervent enemy of New Deal, Roberts did his best to undermine the legitimacy of what he saw as Roosevelt’s revolutionary agenda.In an effort to make the debate in the thirties over American identity racially inclusive, African-American painters Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence created images of black history.