Monica L. Miller is Assistant Professor of English at Barnard College in New York City. Her research interests include 20th and 21st century African American literature, film and contemporary art, contemporary literature and cultural studies of the black diaspora, performance studies, and intersectional studies of race, gender and sexuality. She holds a Ph.D. from Harvard University and a B.A. from Dartmouth College. The recipient of fellowships from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, she is the author of book chapters and articles in The New Literary History of America, the Gender on Ice and Zora Neale Hurston issues of The Scholar & Feminist, Bad Modernisms, and Callaloo. Her current book project, Affirmative Actions: How to Define Black Culture in the 21st Century, examines contemporary black literature and culture from five vantage points in order to assess the consequences of thinking of black identity as “post-black” or “post-racial.”

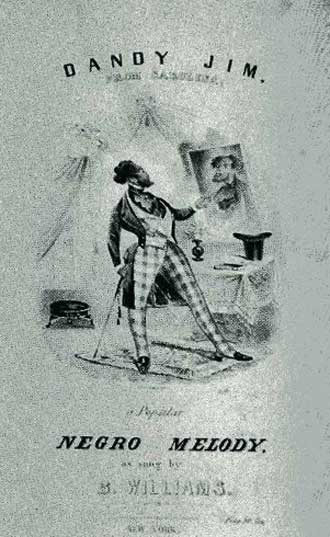

Slaves to Fashion began with a footnote I encountered in graduate school. While auditing a class on W.E.B Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk, I came across a troubling reference to the fact that the revered Du Bois had been caricatured as a black dandy. In the class, we spent even weeks in detailed analysis of Du Bois’s skill as a rhetorician and lyricist. In order to appreciate the truly interdisciplinary nature of his talents, we took very seriously his training as a philosopher, historian and sociologist. The image of Du Bois that emerged was that of an erudite, punctilious, quintessential “race man.” None of this prepared me for the footnote and accompanying illustration from a political cartoon of Du Bois as a degraded buffoon, overly dressed and poorly comported, whose erudition had been turned into what the cartoon called “ebucation.”Only when I began to research the history of dandyism and, in particular, the racialization of the dandy figure, did I realize the complex strategy and history behind that caricature. Dandyism has been used by Africans and blacks to project images of themselves as dignified and distinguished, it has also been used by the majority culture (and blacks) to denigrate and ridicule black aspirations. Slaves to Fashion examines the interrelatedness of these impulses and what the deployment of one strategy or the other says about the state of black people and culture at different moments in history. Although dandyism is often considered a mode of extremely frivolous behavior attentive only to surfaces or facades and a practice of the white, European elite and effete, I argue that it is a creative and subtle mode of critique, regardless of who is deploying it. Though often considered fools, hopelessly caught up in the world of fashion, dandies actually appear in periods of social, political and cultural transition, telling us much about cultural politics through their attitude and appearance. Particularly during times when social mores shift, style and charisma allow these primarily male figures to distinguish themselves when previously established privileges of birth and wealth, or ways of measuring social standing might be absent or uncertain. Style—both sartorial and behavioral— affords dandies the ability and power to set new fashions, to create or imagine worlds more suited to their often avant-garde tastes. Dandyism is thus not just a practice of dress, but also a visible form of investigating and questioning cultural realities.A quick look at the definition of “fop” and “dandy” in the Oxford English Dictionary articulates a difference between them that is extremely important for considerations of the figure’s racialization. A fop (fifteenth century) is one “foolishly attentive to and vain of his appearance, dress or manners.” But a “dandy” (1780) is defined as one who “studies above everything else to dress elegantly and fashionably.”Anyone can be in vogue without apparent strategy, but dandies commit to a study of the fashions that define them and an examination of the trends around—which they can continually re-define themselves. Therefore, when racialized, the dandy’s affectations (fancy dress, arch attitude, fey and fierce gesture) signify well beyond obsessive self-fashioning—rather, the figure embodies the importance of the struggle to control representation and self- and cultural-expression.Manipulations of dress and dandyism have been particularly important modes of self-expression and social commentary for Africans before contact with Europeans and especially afterwards. In fact, in order to endure the attempted erasure or reordering of black identity in the slave trade and its aftermath, those Africans arriving in England, America, or the West Indies had to fashion new identities, to make the most out of the little that they were given. Whether luxury slaves or field hands, their new lives nearly always began with the issuance of new clothes.Enslaved people, however, frequently modified these garments in order to indicate their own ideas about the relationship between slavery, servitude, and subjectivity. For example, there are documented cases of slaves saving single buttons and ribbons to add to their standard issue coarse clothing, examples of slaves stealing or “borrowing” clothing, especially garments made from fine fabrics, from their masters for special occasions. Slaves created underground second-hand clothing markets in major cities to augment their wardrobes and to exchange clothing that identified them when they wanted to escape. In fact, many slaves “dressed up” or “cross-dressed” literally when they absconded, wearing clothing beyond their station or of the other gender in efforts to appear free and be mobile. The black dandy’s style thus communicates simultaneously self-worth, cultural regard, a knowingness about how blackness is represented and seen. Black dandyism has been an important part of and visualization of the negotiation between slavery and freedom.In Slaves to Fashion, I wanted in particular to use the black dandy figure to exemplify the inter-relations between racial, gender and sexual identity and the way these categories are always expressed in terms of each other—but with different emphases during different historical periods and geographical locations. In order to illustrate the black dandy’s embodiment of this intersection of identity markers, I consider the pleasures and dangers of the styling of blackness and self-fashioning as well as the performativity, irony, and politics of consumption and consumerism that define such stylization.The first black dandy in my book, a fabulous black man named Julius Soubise, famous in Enlightenment England for his beautiful dress and outrageous, defiant attitude, often held court in coffee shops that also offered slaves for sale. In this environment, he defied and ironically played with his own former status as a commodity, arriving at these shops in a chaise attended by white footmen, even as his brothers were bought and sold around him. Soubise’s behavior reveals that during that time and forever more, blackness was and is a complicated idea, wholly constructed and always already “performed.”I argue that blackness is itself a sign of diaspora, of a cosmopolitanism that African subjects did not choose, but from which they necessarily reimagined themselves. In Slaves to Fashion, black dandyism is an interpretation and materialization of the complexity of this cosmopolitanism.

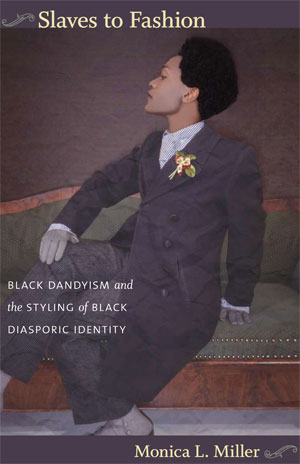

Monica L. Miller Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity Duke University Press408 pages, 9 x 6 inches ISBN 978 0822345855

We don't have paywalls. We don't sell your data. Please help to keep this running!