Monica L. Miller is Assistant Professor of English at Barnard College in New York City. Her research interests include 20th and 21st century African American literature, film and contemporary art, contemporary literature and cultural studies of the black diaspora, performance studies, and intersectional studies of race, gender and sexuality. She holds a Ph.D. from Harvard University and a B.A. from Dartmouth College. The recipient of fellowships from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, she is the author of book chapters and articles in The New Literary History of America, the Gender on Ice and Zora Neale Hurston issues of The Scholar & Feminist, Bad Modernisms, and Callaloo. Her current book project, Affirmative Actions: How to Define Black Culture in the 21st Century, examines contemporary black literature and culture from five vantage points in order to assess the consequences of thinking of black identity as “post-black” or “post-racial.”

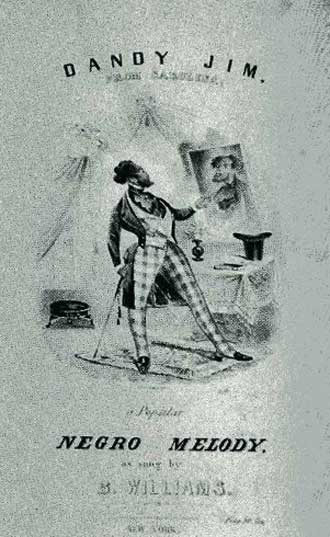

In order to illustrate the way that a black dandy can embody complex and even competing notions of blackness, meet “Dandy Jim, from Carolina,” a theatrical figure made famous by nineteenth-century America’s most popular entertainment, blackface minstrelsy. His song in the minstrel show begins:

I’ve often heard it said of late

Dat South Carolina was de state

Whar handsome niggars bound to shine

Like Dandy Jim from Caroline

I went one ebenin to de ball

Wid lips combed out and wool quite tall

De ladies eyes like snowballs shine

On Dandy Jim from Caroline.

Narcissistic to a fault, Dandy Jim was certainly one of those characters whose self-aggrandizing attitude, accompanied by outrageous dress, titillated with equal parts threat and appeal. “Going black” in the blackface minstrel theater means much more than blackening up; the minstrel show was a world in which anxieties about the inter-relation between race, gender, sexuality and class seemingly had free reign.While largely overshadowed by the character Jim Crow, a denizen of the plantation, the blackface dandy was a particularly potent force in the antebellum minstrel show. In particular, Dandy Jim and his dandy predecessors, Long Tail Blue and Zip Coon, provided a way for working class, immigrant white performers to ask questions plaguing nineteenth-century Americans. What if blacks were free? What if they had money, access to education, unchecked social, cultural, and economic mobility? The blackface black dandy costume, often an elaborate misquotation of elite fancy dress, and pretentious, loud-mouthed, ridiculous (yet funny and provocative) behavior answered these questions, or at least attempted to represent them.Although the early minstrel show presents the dandy in slightly different guises, what remains constant about its portrayal of blacks in fancy clothing is the figure’s association with sexual threat and class critique. In the case of the blackface dandy, the donning of elite clothing images a desire for social mobility—and for the most extreme form of integration, interracial sex.What is surprising about blackface dandies is the degree to which they succeed at their plans—for example, when Dandy Jim’s fellow, Long Tail Blue, has his long blue coat split by a watchman in his song, a clear assault on his phallic power, it is very quickly repaired. Even though Long Tail Blue does not complete a conquest of any white “galls” at the end of his song, which is his intention, he is still very much in the chase.Dandy Jim is involved in similar antics: a narcissist intending to cut a figure at the ball, and, in some versions, woo “lubly Dine” into providing him with “eight or nine/ Young Dandy Jims of Caroline,” Dandy Jim boasts of a sexual prowess that is definitively linked to his appearance as a “handsome nigga [who is] bound to shine.”Unlike that of Long Tail Blue, Dandy Jim’s lust remains within his own race and social conventions: “Lubly Dine” is a fellow black who Jim actually marries in the song. However, despite the placement of Dandy Jim’s excessive sexuality within an intra-racial family structure, his quest to populate the world with as many little dandies as he can, “ebery little nig she had/ Was de berry image ob de dad,” is nevertheless threatening. The (white) anxiety of black freedom and equality that black dandies embody is not just one in which social equality leads to miscegenation (as in the case of Long Tail Blue) but one which seems to equate miscegenation with the threat of mere black presence and visibility.Long Tail Blue, Zip Coon, and Dandy Jim menace even as they amuse, revealing the affinity between effeminacy associated with extreme attention to dress and appearance, and a hyper-masculinity linked to a sexual rapacity that exceeds racial boundaries.Despite the fact that blackface dandy’s sexual threat is almost always figured as heterosexual, the figure has a queer effect because of the way in which his racialization is so bound up in his sexuality and vice versa. This is not to say that the blackface dandy himself is queer; to do so would be anachronistic and to limit, in some ways, the total force of his boundary crossings. Instead, the figure’s excesses allow us to see from a contemporary viewpoint the way in which the minstrel show worked hard to express anxieties about blackness in terms of the other markers of identity and vice versa.When looking at the show, we forget that the “galls” being pursued here by white men in blackface are themselves white men in blackface and drag. From this perspective, the blackface dandy’s antics signal the intriguing possibility and threat of both interracial and same-sex liaisons that have to be pursued and are often realized through blackness. The blackface minstrel show featuring the black dandy was not, in any way, an arena in which the anxieties attending race, class, sex and gender were contained. In fact, the dandy on stage, a white performer in blackface, often cross-dressing in terms of race, gender and class, comes alive in the pursuit and performance of these anxieties, in the production of a queerness that lingers after the curtain goes down and the burnt cork removed.While I do not directly investigate contemporary “dress debates” such as Bill Cosby’s call for young black men to hitch up their pants, or what it means for P. Diddy to be nominated for “Designer of the Year” for his Sean Jean line while employing “butler” and stylist Farnsworth Bentley to carry his umbrella in St. Tropez, or even why Andre 3000 of Outkast frequently dons a straw boater in homage to the older black men in his Atlanta neighborhood, it is my hope that the history and case-studies that I do provide in the book give readers a sense of how and why dress matters for black people.Whether practiced on the streets of metropolitan Europe or America, seen on the colonial or blackface minstrel stage, textually illustrated in novels hoping to define New Negroes and race men, or experienced visually in photographic exhibitions in the galleries of Chelsea and London today, black dandyism is a strategy of survival that has a long and multifaceted history.Black dandyism is, above all, an investigation of the use and abuse of image. As Iké Udé, an artist/aesthete whose self-portrait is my book’s cover, says, “In the end, a dandy’s style is not just about form and substance. It is also about the luxurious deliberation of intelligence in the face of boundaries.”

Monica L. Miller Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity Duke University Press408 pages, 9 x 6 inches ISBN 978 0822345855

We don't have paywalls. We don't sell your data. Please help to keep this running!