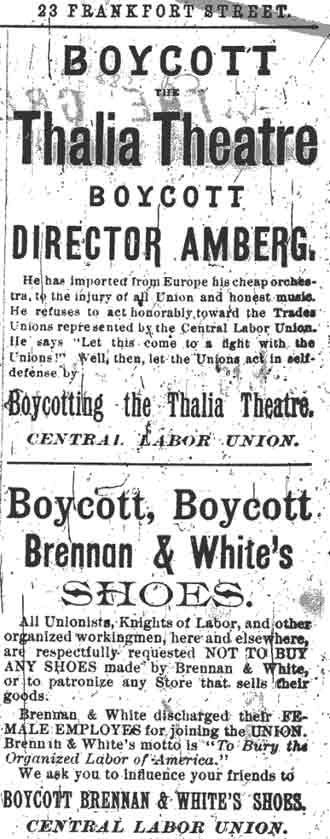

Buying Power traces the origins and development of consumer activism in America from the 1760s to the present. Historians and other scholars have written about discrete boycotts or closely conjoined sets of boycotts (such as those of the 1760s and 1770s). My book, by contrast, treats consumer activism as a continuous and significant American political tradition.To say that boycotts constitute a political tradition is not to claim that that tradition was monolithic. From the beginning, boycotts were deployed by groups with very different political agendas. Two chapters early in my book, for example, contrast antebellum America’s abolitionist boycotters of slave-made goods and white Southern proponents of “non intercourse” with the North. These groups employed nearly-identical tactics to promote antithetical goals, putting their shared belief in the power of organized consumption to work for opposing causes.One advantage of studying consumer activism from a long-term perspective, then, is that this vantage reveals that recent conservative boycotts (such as the Southern Baptist boycott of the Disney corporation) are not departures from a monolithic “progressive” tradition.Another advantage of studying consumer activism from a long-term perspective is that it makes salient both the continuities and transformations within this more than two-century tradition, setting into relief aspects of consumer politics that developed and changed over time.It was not until the twentieth century that consumer politics came to be characterized by a conception of “the consumer” as needing protection. Moreover, it was in this period that there emerged self-described consumer organizations, groups that saw their task as representing, defending and lobbying for consumers themselves. These groups established consumers as one interest group among many in a pluralistic society—rather than as an embodiment of that society, as consumers had been thought of by most nineteenth century consumer activists.These groups coalesced in the 1930s into something known as the “consumer movement,” an organized political effort on behalf of consumers, whose chief aim was, as Helen Sorenson described it in her 1941 book, The Consumer Movement, “protecting and promoting the consumer interest.” The federal government itself came to understand the protection of the consumer interest as one of its duties, starting with the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906, through the various consumer advisory boards of the New Deal, and through the President’s Special Assistant for Consumer Affairs, begun under President Lyndon Johnson in the 1960s.What distinguished the “consumer movement” from previous and contemporaneous movements of consumers was precisely this emphasis on consumers themselves as the chief beneficiaries of political activism. By contrast, neither Revolutionary boycotters, “free produce” campaigners, nor even the turn-of-the-twentieth-century founders of the National Consumers’ League saw themselves as part of a “consumer movement.” Rather, these groups mobilized consumers not for the benefit of consumers but on behalf of the nation, the slave, the worker, or the poor.