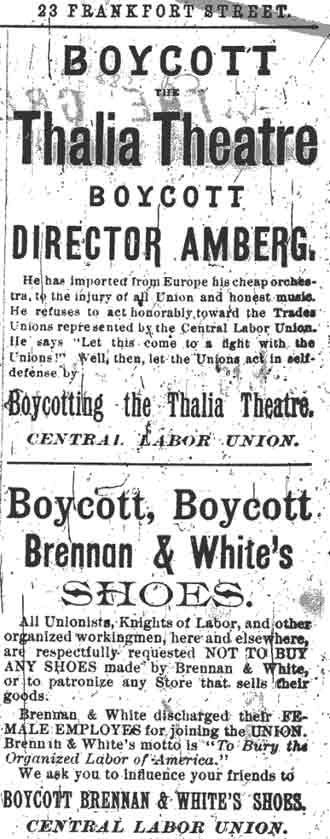

This morning, October 1, 2009, I picked up the New York Times to notice a full-page ad on the back of the news section. It was prepared and paid for by “The Center for Consumer Freedom.” The group, going by the motto of “Promoting Personal Freedom and Protecting Consumer Choice,” opposes taxes being considered by New York City and elsewhere on soda and junk foods. The ad begins, “Are you too stupid…to make good personal decisions about foods and beverages.” Arguing against the “campaign to demonize soda” the advertisement blasts “food cops and politicians” for “attacking food and soda choices they don’t like.” Another of their ads warns about “Big Brother” in the “Big Apple.” The group’s print ads provide a present-day example of the language of what I call “conservative populism,” whose origins I trace in my book.The final chapter of Buying Power examines the battle for, and ultimate defeat of, a Consumer Protection Agency (CPA), a cabinet-level department, which came tantalizingly close to becoming a reality several times in the 1970s. The CPA was defeated by a powerful lobby of various business organizations, led by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. But, in the end, the bill was, as the Wall Street Journal observed in 1978, “killed by words,” that is by the language of conservative populism that was invented by opponents of consumer protection and still lives on.Beginning in the 1960s, this lobby successfully popularized the idea that consumer protection was a form of government coercion sufficiently frightening that it was best understood as “Orwellian.” This, I argue, was the opening wedge in what became a rhetoric of describing the broader liberal project as one that promoted unfreedom.The specifics have changed in the last forty years, but the fundamental accusation has not. Currently, the same criticism is being used against President Obama’s proposed Consumer Financial Protection Agency. (I outline the argument that consumer protection is an important element of modern liberalism in a brief piece titled Consumer Protection Redux.)In the late 1990s, I began to research a book on consumer activism in the twentieth century. Several years into my research, I realized that I could not tell this story without showing what had come before. Consumer activism in the years before 1900 turned out not to be merely prehistory to the “real” story of consumer activism but an essential part of it.Although historians, especially T. H. Breen, had highlighted the importance of Revolutionary era consumer politics, very little work had been done on the nineteenth century. For this reason, I most enjoyed researching the chapters of Buying Power that cover relatively unknown consumer campaigns—including those by abolitionists and Southern nationalists in the antebellum era, and by labor and African American activists in the postwar years. These campaigns, I believe, helped invent the vocabulary and the underlying philosophy that continue to guide contemporary boycotters. The core principles of boycotting–such as the use of the modern sounding phrase “conscientious consumer” and the concept of long distance solidarity—were firmly in place by 1880, the year that the word “boycott” was coined.Despite the importance of this nearly continuous history, one of the most striking characteristics of consumer activism is the lack of knowledge that boycotters generally have had about their predecessors. I tried to understand why, compared with most other social movements, boycotters have tended so quickly to forget their history. At the same time, although they may not have been able to name their forebears, boycotters have almost always drawn on the methods and philosophies of those who came before them. I’m conflicted about whether this process of forgetting is part of what has accounted for the prevalence of boycotting. Since most boycotts throughout U.S. history have failed to achieve their goals, perhaps those who remembered the past would have been disinclined to try a seemingly ineffective tactic.Writing this book made me acutely aware not only of the genealogies of consumer activism and its rhetorics (both for and against) that continue to inform the consuming practices of the present but also of the artificial nature of our theoretical approaches, especially to the standard periodization of U. S. history that takes the Civil War to be the defining divide.Defying the conventions of academic departments, the history of consumer activism was neither strictly antebellum nor postbellum; it was both. I would like to see more work that traces concepts and practices over the course of our history. Such works can shed new light both on the concept being traced, and can also, as I believe Buying Power does, provide a way to reframe U. S. history more generally.