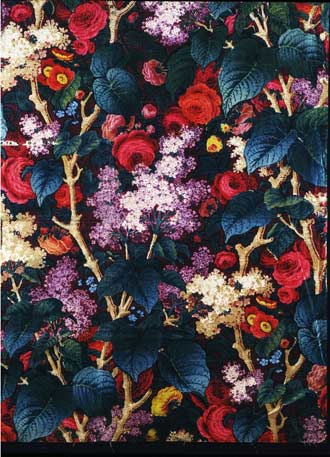

The idea that interiors reveal personalities is such a truism of contemporary culture that it is difficult to imagine that it was not always so. While the well-to-do in previous eras lavished attention upon their mansions and country houses, such refurbishments more often attested to the dynastic ambitions of a family than the inner self of a particular lord or lady. If a few individuals in the Georgian period, such as the architect Sir John Soane, had aimed to transform their dwellings into monuments to their unique sensibilities, their efforts lay far beyond the imaginings or pocketbooks of the vast majority, whose concern was with comfort and propriety rather than romantic creativity.What changed during the Victorian period was not just the purchasing power of middle-class Britons, but understandings of the self. In the mid-nineteenth century, Victorians had most often conceived of the self in terms of character, a religiously-inflected term that chiefly connoted a moral condition. A man’s character might be built through painstaking instruction and introspection; however, the path to improvement was tortuous. By the 1890s, there was a new, seemingly secular way of thinking about the self, expressed in the concept of personality. If character was demonstrated by self-control and self-denial, a display of “personality” required individuality. Personality was malleable, creative, and complex; it accompanied a new, psychological conception of the mind. The home was the staging-ground for this new idea of personality. In an increasingly heterogeneous middling stratum, a personality, expressed in a distinctive interior, became a necessary asset. The consumer boom—combined with this new confidence that possessions could communicate their owner’s individuality—made for a giddy period of acquisitive experimentation. Since furnishings made the person, no decorative scheme was off-limits, and “quaintness,” the quality of being out of the ordinary, was the desired effect. The spinster in Sussex who wallpapered her bedroom with black-bordered In Memoriam cards, the hostess who placed her guests in “spring,” “summer,” “autumn” and “winter” rooms according to their age belong to the human comedy of fashionably eccentric furnishing at the fin-de-siècle. So, too, do the young couples who decorated their drawing-rooms according to the prevailing fashions of pan-Asianism, with Indian-printed textiles cheek by jowl with fancy Japanese fans. Why not a Tess of the d’Urbervilles room, wondered one Thomas Hardy fan, envisioning a décor imbued with the “spirit of the West Country and the gloom of the book.”Long the cradle of the family, the home became something more in the Edwardian period; the domestic interior literally helped to create the individual. C.S. Lewis was one of many who credited his boyhood home, considered apart from the members of his family, as “almost a major character in my story,” viewing himself as “a product” of its corridors and rooms. Yet the task of communicating one’s individuality would prove a far more perilous undertaking than middle-class furnishers had envisioned. What if one inadvertently broadcast the wrong message? When furnishings made the person, every decision could become a cause for regret.In Britain, the locomotive of Victorian acquisitiveness was powered, in part, by an engine that ran on the unlikely fuel of spiritual striving. My book deals with the pentimento of militant Christianity, the shadowy imprint that remained even after damnation and eternal punishment were no longer preached from the pulpits. Edwardian critics liked to believe a world of difference existed between themselves and their more devout ancestors. But the distance between self-denial and self-expression was perhaps not as great as we might imagine. Most significantly, evangelicalism forced a concentration upon the self which was, in the generations that followed, modified, but not abandoned. While wealth, as Max Weber believed, may well have exercised a “secularizing influence,” that secularization was itself indelibly colored by religious antecedents.Consumption served to define and to differentiate an extremely heterogeneous middle class. Taste—no less than occupation, religion, or political affiliation—should be considered a crucial ingredient in the making of middle-class Britain. Consumerism has re-oriented the social and political landscape. Writing in 1913, the historian G.M. Trevelyan saw a connection between the diffusion of consumer goods and the extension of the franchise. The right to vote, he observed, only came, “when the coats [that working men wore] were better.”