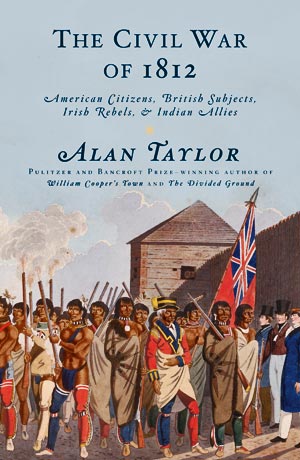

I came to see the War of 1812 as a civil war between kindred peoples, recently and incompletely divided by the revolution. To call the War of 1812 a “civil war,” now seems jarring because hindsight distorts our perspective on the past. We now underestimate the uncertainty of the post-revolutionary generation, when the new republic was so precarious and so embattled. We also imagine that the revolution made a clean and lasting break between Americans and Britons as distinct peoples. In fact, the republic and the empire continued to compete for the allegiance of the peoples in North America: native, settler, and immigrant.

On both sides of the border, the people thought of the new war as continuing the revolutionary struggle between Loyalists and rebels. The revolution had divided Americans. While the majority supported an independent republic, a strong minority remained loyal to the union of the empire under the leadership of the king and parliament. When the Patriots won their revolution, many Loyalists became refugees in Canada.So the revolution created a new boundary between the victors in the United States and the Loyalists in Canada. But that border seemed fluid, weak, and unstable. Leaders on both sides expected the border to collapse, sooner or later.

Either the United States would collapse, with the British picking up the pieces, or the Americans would sweep into Canada to oust the British from North America.Meanwhile, within the republic, bitter partisan politics led the dominant party, the Republicans (of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, not today's Republicans) to denounce their Federalist opponents as crypto-Loyalists. Some Federalists became so alienated from the national government that, during the war, they covertly helped the British as spies and smugglers. Many more Federalists hoped that defeats would discredit and topple the Republicans from power. In turn, those Republicans believed that the Federalists were conspiring with the British to break up the union. And the leading Federalists in New England did flirt with seeking a separate peace with the British.

The war also embroiled native peoples. In the Great Lakes country, the Indians allied with the British to roll back American expansion. By intimidating and defeating American forces, the native warriors obliged the republic to seek their own Indian allies from the reservations within the United States. The fighting especially divided the Shawnee and the Haudenosaunee nations.