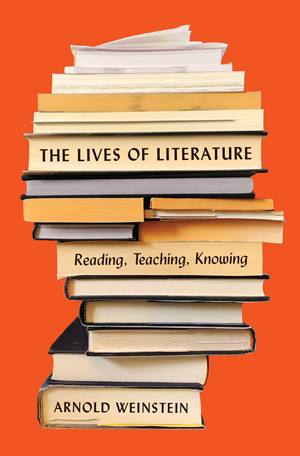

The Lives of Literature tackles the central, all-too-unasked, question that undergirds my teaching and writing career: why read literature? It’s the question all students ponder—why read these books?—and it seems especially urgent today, given the ever greater prestige of the STEM fields and the shrinking enrollments in the Humanities throughout higher education.

The surprising word in my book’s title is “knowing.” What do we “know” after we’ve read a novel or poem or play? From an informational point of view: nothing verifiable or easily testable. Certainly nothing comparable to the theorems and truths of the sciences and even the social sciences. But there’s the rub: literature’s truths are of a different sort altogether. Just as life’s truths are. I know that 2 + 2 = 4; I know my wife and children. Both statements are true, but they are radically different. One is factual, objective; the other is existential, subjective.

My argument is that literature both illuminates and engenders a different kind of knowing: existential, but also experiential, moral, neural, sentient. And I think that’s why we read it. We experience—safely, at a distance, only vicariously, and ‘exitably’—the crises and feelings of Oedipus, Lear, Cathy and Heathcliff, Huckleberry Finn, Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, Faulkner’s Quentin Compson, Morrison’s Sethe.As an identical twin who was often mistaken for his brother during our childhood, I have always had a rather porous sense of people’s outlines and identities.

Most people don’t. But only now do I realize how much that basic experience has shaped my understanding of books. Not only can our outward forms be illusory or subject to change, but there is something at once deeply promiscuous and deeply ethical in all this: are we capable of seeing others as ourselves (as the Good Book says)? Shape-shifting happens. President Obama said of Trayvon Martin: he could have been my son. Readers might—must?—intuit, at some unexamined level, in the books they read: this could be, could have been, me.And nothing here is easy.

So many of our greatest books are about people discovering, with horror, that much of what they have believed true (about themselves, about others, about the world) is bogus, turned inside-out. It is often unsurvivable. This is what I call “the cost of knowing.” But the reader, who is a fellow-traveler in this journey toward dark knowing, does not bleed or die. Long ago Aristotle claimed that watching tragedy onstage was for the audience “cathartic,” purgative. I think reading literature can—should—be seen in just this light. It is more than a lesson: it is an experience. And the role of the teacher is to help students discover just how potent and far-reaching this encounter can be.