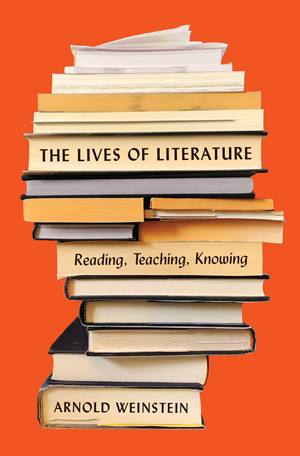

This book is intentionally hybrid: it mixes literary criticism, commentary on teaching, reflections on the role of the Humanities, and personal memoir. This was a risky choice, on my end, and questions were raised by the Press’s readers about this mélange, when the manuscript was being evaluated for publication. All this bears on what I can recommend to a reader, for sampling, for getting a taste of what the book’s about.If you’re interested in literature, but sometimes wonder what all the fuss is, I suggest that you read my chapters on “The Cost of Knowing” and “The Map of Human Dimensions.”

Here is the “lit/crit” component of the book. The essays about ‘Knowing” focus on Shakespeare, Emily Brontë, Melville, Dickinson, Twain, Kafka, Faulkner, and Morrison, whereas those about “Human Dimensions” deal with Baudelaire, James Merrill, Strindberg, Joyce, Godard, and Calvino. The texts I write about—many of them canonical—constitute the backbone of my argument about why literature matters. One set of analyses gauges the crises that come about when all that we think we know is exploded; the other set maps our astounding whereabouts in time and space, occurring in our brains and on show in our best books.

There is nothing abstract or exotic here; this is meat-and-potatoes. All of them are testimony to literature’s unique power.If you’re drawn to the STEM-fed crisis of the Humanities in higher education today, I’d recommend that you read my chapter on the “3 R’s,” for it utilizes the venerable triad of Reading/Writing/Arithmetic as a kind of test-case for what Literature does. We know, of course, that reading and writing are central to literature, but the texts I discuss—from Faulkner, Knut Hamsun, and Kafka—are intentionally extremist in nature, laying bare the rationale and purchase of these two central modes of representation. It seems to me that these two activities—each devilishly hard to teach, by the way—lay the very groundwork for what Education aims for: self-impowering entrance into the word-world, and discovering/recovering the (sometimes awful) record of our doings, the “tale of the tribe.” As for Arithmetic, you may assume literature has no light to shed; my argument there has some whimsy, but it is quite serious in seeking to illuminate limits and boundaries, to explore what is measurable in numbers versus words.

Finally, the book deals with my lifetime in the classroom: what the challenges, rewards and pitfalls are, and have been. These matters have their historicity. I have had the unusual pleasure of teaching in many distinct modalities: classroom, video cassette, CD, online, Zoom. Each has different audiences; each has its own terrain, rewards and costs. I have taught university students at Brown, high school students throughout Rhode Island, and adult audiences throughout the country.

Their interests and needs do not easily align. So I include, late in the book, a chapter where the wryer, failed and more absurd experiences of teaching are (at long last) acknowledged and dealt with. I call them “Gaffes.” Friends who have read my book tell me this is where they started.My expectations for The Lives of Literature are uncertain. This is my 9th—or 10th, depending on how you count—book, and it is very possibly my last. But it comes out at a tricky time.

Our culture today is riven, in more ways than one. I am concerned about the reception that may await a book dealing with the Western canon, written by an old white male. In some quarters such credentials and aims are dicey, perhaps even toxic. There is a widespread (and, yes, justifiable) suspicion that my demographic has hogged the stage for quite some time now. Time for other voices.

This is especially distressing, because the book itself is timely: it addresses the diminishing prestige of the Humanities, and it offers up a view of literature that has broad appeal to the larger reading public, well beyond the academy. The existence of countless reading groups and book clubs throughout our country testifies to the ongoing vitality and reach of great books, from long ago to the present.

And to a hunger to plumb those books, to derive nutrients from them. I believe The Lives of Literature meets that hunger, that demand. Further, I know I could not have written it earlier, because it has taken this many years in the academy (54, to be exact) to gain a fuller, more longitudinal sighting of what a career of teaching literature signifies: what I tried to do, why I did so, what I wrought, and whether it matters.

All this is why I appreciate the unusual opportunity to shape this Rorotoko Interview myself. It gives me the last word. And I guess that is, , what my book is: a literature professor’s last words about what he has spent his life doing.