Given the philosophical training I received, I was rather frustrated that the recent philosophy of the embodied, extended, embedded, and enactive mind, collectively known in some philosophical circles as 4E, had consistently failed to historicize claims about the links between embodied perception and action. There is some fascinating work in this area from figures such as Andy Clark, Alva Noë, David Chalmers, Kevin O’Regan and others that I read and enjoyed as a graduate student. But typically their arguments failed to account for the history of science, and failed to acknowledge precursors within their own discipline of philosophy, such as the phenomenological psychology of Maurice Merleau-Ponty or Erwin Straus.

This motivated me to fill gaps in our historical understanding of the inner senses, and to draw connections between that underexamined history of sensory science and the more recent treatment of those same senses in specialized neuroscience and psychology journals.

Take the example of pain, the subject of the second chapter. Is pain a sense? For a while it was indissociable from forms of touch. Ernst Heinrich Weber and his student Gustav Fechner, who instigated a subdiscipline of physiology that became known as psychophysics, measured skin sensation and compared it across human subjects in their laboratories. One thing that emerged through this work was that pain became a distinct and measurable sensation, which might seem counterintuitive today. Following the thread of this one sense we go through some surprising territory, as theorists of pain in the mid-twentieth century start to compare the specialized nerve pathways to a cybernetic system.

What bookends this chapter on pain is a recent study in psychology by a team from Harvard and the University of Virginia who in 2014 found itself in news headlines around the world. The team claimed that experimental subjects who were left alone and without stimulation for long periods of time would shock themselves, causing themselves pain. These were—literally—sensational findings, but the point of starting and ending the chapter with this story was to interrogate the organismic function of pain as a sensation, as well as to determine the neurological pathways. What started in a lab in Leipzig in the 1830s remains highly significant in 2014, even if the understanding now is more nuanced.

This type of journey, from the seemingly obscure origins of the study of inner sensation to more recent case studies and news reporting, is replicated in several of the chapters.

There are other narratives woven between chapters. One of the key figures who reappears at different points throughout the book, the Oxford-based physiologist Sir Charles Sherrington, exemplifies the application of scientific knowledge to industrial purposes during the First World War. In fact, Sherrington’s work directly led to social reform around working hours and labor conditions in factories.

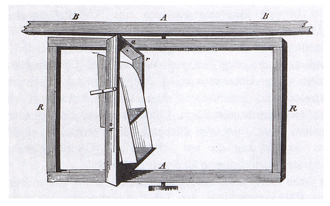

As Chapter 5 on fatigue reveals, Sherrington left his comfortable office and laboratory and cycled sixty miles to a munitions factory in Birmingham where he was supposed to be observing workers. He spent a great deal of time on the factory floor and ended up writing a sort of ethnography. Munitions factories were incredibly dangerous, and he was tasked, as chair of the newly-formed Industrial Fatigue Research Board (IFRB), to report to the British government about safety and efficiency.We see this movement of physiology from the laboratory to the workplace with other scientists discussed in the book, including Angelo Mosso, Jules Amar, and Étienne-Jules Marey.

The IFRB report, however, led directly to social reform and modification of laws around working hours and conditions through the Factories Act in the United Kingdom. Sherrington’s lab work, and his impressive observations on the integration of systems of reflexes in the organism, also features heavily in the first chapter about the mapping of the sensorimotor cortex. So, as you see, the focus within the book shifts from particular discoveries in the history of neuroscience to a more wide-angle social landscape at various points.